Patriot cause

Every year when the Fourth of July approaches I think about the remarkable series of events that resulted in the independence of the American colonies and the founding of a new nation. And every year I pick up a book to refresh my memory.

This year I read Joseph J. Ellis’s Revolutionary Summer: The Birth of American Independence. I’m amazed once again by how unpredictable the outcome of the War for Independence was. Very few British politicians and military leaders took the Declaration of Independence seriously; most assumed that the largest, best-equipped, and best-trained army and navy in the world would quickly crush the rebellion. Yet after the final battle was fought at Yorktown, Great Britain had suffered 40,000 casualties, spent 50 million pounds, and lost the colonies.

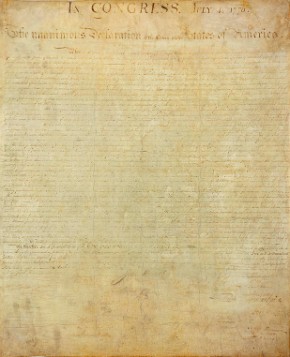

One of the fatal assumptions was that support for the revolutionary cause was thin among the colonies. But as Ellis argues, during the “revolutionary summer” between May and October 1776, “a consensus for American independence emerged and was officially declared, the outlines for an American republic were first proposed, the problems that would face its future were faced and finessed.”