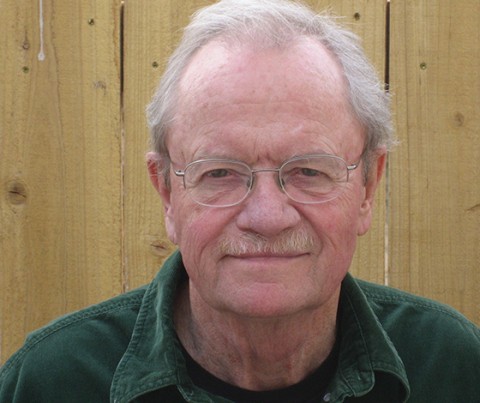

The precious ordinary: Novelist Kent Haruf

Kent Haruf’s novels are set in the fictional town of Holt on the eastern plains of Colorado. His 1999 novel Plainsong was a finalist for the National Book Award. Haruf’s father was a Methodist minister in Colorado, and Haruf has often drawn on that legacy in his fiction. Only in his latest novel, Benediction, has a minister been a central character in his fiction.

Can you tell us about growing up as the son of a Methodist minister in the West?

Until I was about 12 years old, we lived in three little towns in eastern Colorado. In each town, my father was the preacher at the only Methodist church in town.

My dad was a country man. He fit in wonderfully in those little towns; people loved him. When he was in college, they called him Lovable Louie, because he was such a joyful man.

I cannot say that he was a great pulpit speaker. He was adequate. But once he got out of the pulpit, he shone. When he walked into a room, people just wanted to be near him. He had a great sense of humor. He was a wonderful storyteller.

My mom was more ambitious for him than he was for himself. My mom grew up in South Dakota on a sheep ranch, and they met at Dakota Wesleyan University. My mom was very precisely spoken. I remember hearing them as they lay in bed on Sunday morning. He would read his sermon to her, and she would correct any grammar that needed to be corrected. My mom was his best friend, his confidante, and his adviser. He called her “Pal.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

What was church like for you?

We would endure church. I hated Sunday school, because nothing ever happened. When I was in high school, we spent time every Sunday trying to memorize the Apostles’ Creed. There was an old guy trying to teach it to us, and it was a waste of time. I still don’t know it.

The only thing I remember with any pleasure was learning to sing the song “Do Lord.” I loved that. In the summer we had to go to Bible school, which I also hated. Best thing about that was the cookies.

My younger brother Mark and I always had to sit with my mother in church. There was a big clock on the wall that we would stare at to see how much longer church was going to last. My little brother and I got into the habit of seeing how long we could hold our breath. We would watch the minute hand go around and test ourselves. The other thing we would do is tell my mom that we had to go to the bathroom. But you would have to ask her in the last 15 minutes; otherwise you would have to come back.

It was so funny to watch people sleep in church. Their heads would rock back, mouth open, and then all of the sudden they would wake up. One astonishing time, I watched a woman nurse a baby in church. Then Mark and I could quit watching the clock and watch this woman instead.

Any other church memories?

Back in those days there would be gospel singers coming through, black guys from the south, and they would stay with us overnight. That was partly because hotels in those little towns were terrible and partly because those men might not have been accepted. I don’t know. But my dad had played football with a black guy at Dakota Wesleyan, and he had very strong feelings about race. He didn’t talk much about it, but he acted on it. I grew up thinking that’s what people did: they read books and they told stories and they extended hospitality to people from different backgrounds.

What is the legacy of Methodist Christianity for you?

What I saw as a kid was hypocrisy, and it really galled me. I would see people profess certain things on Sunday morning, and I would see different things during the week: meanness and alcoholism and violence and unkindness.

As I got older, I felt that the Methodist hierarchy had mistreated my father because he was a country person. He wasn’t an intellectual, he was not a sophisticated speaker, but he was, in my view, a true Christian. They misjudged him for their own reasons. By the time I was 18, I had left the church intellectually and emotionally.

Did that hurt your parents?

They never understood it, and we never talked about it. When I went home, I would go to church with my family. I never had a conversation about religion with my father in my life. He demonstrated his faith by his actions.

Though religion was central in your upbringing, it doesn’t come up that often in your fiction.

One time I was giving a talk at a university, and a guy told me that Plainsong has no religious themes because there are no scenes set in a church. I suggested to him that Plainsong is full of spiritual moments, if maybe not orthodox religious moments.

Whenever someone takes in someone who needs help or befriends someone who is lonely—those are religious acts. They fit the basic tenet of all religions. Jesus said, “What you’ve done to the least of these, you have done to me. I was hungry and you fed me; I was naked and you clothed me.” That is exactly what some people in the novel are doing. It is not under the auspices of a church, but it is the essence of compassion and spiritual feeling.

Raymond McPheron in Plainsong is a kind of small-town—I wouldn’t say saint, but he is a religious figure. He would never say that about himself, and people would never really understand that. But they might be attracted to his character.

In your fiction, you very rarely tell us what your characters are thinking. Why is that?

That is a deliberate choice on my part, and it is has become more conscious the longer I have written. To me, it is a cheat to go into someone’s mind. It is a way of avoiding the difficulty of having to create scenes.

What is more powerful, more vivid, more indelible is to create a scene where people are doing the things they are thinking. I have become more adamant about showing what people are thinking, not telling you what they think. I don’t want to get between you and that setting and those characters. It is almost like a screenplay. It is external rather than internal.

Why did you put a minister into Benediction ?

I didn’t start there. I imagined Dad Lewis, Mary, Frank, and Lorraine. Then their neighbors. Then I began to wonder who else would come to see Dad Lewis in his dying days. In a small town, the preacher would come. My dad went to see dying people all the time. That was a familiar fact for me.

I wanted to create a different kind of preacher—someone who had his own problems and who would be in opposition to what would be normal in a small town like that. Reverend Lyle had had trouble in Denver because he had supported a gay preacher. I started out with Reverend Lyle being a Methodist because that’s what I knew, but I decided that was going to confine me too much, so I messed around with that some.

Not too much, though, because he does have a son named John Wesley.

True. I thought about naming his son Calvin but decided against it. I have him give a sermon based on the Sermon on the Mount because to me that is the most important message that Jesus ever gave, maybe that anybody ever gives: to love your enemy. How can you do that? It is all the more difficult after 9/11.

There are only one or two ways of dating this book, and one is that Reverend Lyle mentions bodies falling from the towers. So we know this sermon is given some time after 2001.

This country was, as we all know, horrified, rightly so, by what happened at the World Trade Center. But I think we completely missed a chance as a country to respond. We reacted in the traditional way of violence against violence. And we didn’t fix a damn thing. We made more enemies for this country.

There is another moment in Benediction when Reverend Lyle names something that seems crucial in your work: “the precious ordinary.”

I don’t think I knew it at the time, but that does sum up what I hope to achieve: to do what Chekhov did, to show the beauty and the significance of ordinary people and ordinary moments. To make significance out of trivialities, not to be blind to them, not to miss them. He is trying to see that.

When I think about Reverend Lyle’s character, what I see is that he is trying to see what real life looks like because he doesn’t understand it. He is a pretty good pulpit speaker. He is dramatic and a man of principle. At home he is pretty much a failure as a husband and a father. Until his son tries to commit suicide, then I think that humanizes him. He is able to take his son down from that terrible place and to hug him, and even to call him “honey.” That was a huge difference from what he had been doing.

I think it is possible for Reverend Lyle to say things like “the precious ordinary,” whereas other characters like Dad Lewis, for example, or Raymond—they can’t say that kind of thing. But someone who has some skill with language would be able to say that.

Sorrow and joy seem intermingled in your fiction.

Sorrow and sadness are part of these stories and of my life. You wake up with it, but it’s not all that is there. The way I think about it, these characters have to stack joy on top of sorrow. You have to work harder at recognizing joy than you do sorrow. I am much more accustomed to adversity. I can deal with adversity. I’ve been doing it for 70 years.

I don’t know what to do with joy. I don’t know how to take it in. Sorrow is the constant: that is the condition of being human. Maybe it isn’t original sin, but we are born into sorrow.

But people are capable of such flashes of beauty. I talked to a book club awhile back about Benediction. One of the women in the group got really exercised about Reverend Lyle’s wife. She was up in arms: “That woman should never have left her son with her husband.” A woman sitting near her said, “I did that.” It got really quiet in the room. She said, “When my husband and I separated, I left my son with him, and I took the two girls with me.”

She didn’t say anything more, but it was clear that 50 years later, it was still on her mind. I wanted to kiss her. What bravery. What courage to say that. The people in that group didn’t know each other that well. And the statement didn’t seem to make an impact on the other woman. But it changed the rest of us. That was one of those rare, beautiful human moments. And it had something to do with religion.