Our Augustine

This is proving to be a banner year for culture-hero jubilees. On May 16, 250 years ago, the young Scottish laird James Boswell met the middle-aged English polymath Samuel Johnson in a London bookshop and recorded his first impression: “Mr Johnson is a man of a most dreadful appearance . . . a very big man . . . very slovenly in his dress . . . Yet his great knowledge and strength of expression command vast respect and render him excellent company. He has great humour and is a worthy man. But his dogmatical roughness of manners is disagreeable. I shall mark what I remember of his conversation.”

German composer Richard Wagner and Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard were born in the same month of May 200 years ago—one imagines an astrological chart showing Sturm und Drang in the ascendant.

Swami Vivekananda was born 150 years ago and in turn gave birth to the interfaith movement at the 1893 Parliament of World Religions, held in Chicago.

And a mere 50 years ago, still in living memory, the world lost the physical presence of C. S. Lewis, whose big, humorous, slovenly and dogmatical frame contained much of Samuel Johnson, more than a little of Wagner and Kierkegaard, and perhaps a touch of Vivekananda.

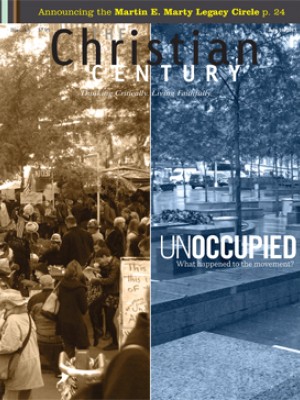

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Not one of these jubilarians has faded from view, but Lewis has been enjoying the lion’s share of public attention. A year of Lewis celebrations will culminate on November 22nd (the death anniversary he shares with John F. Kennedy and Aldous Huxley) in the unveiling of a memorial stone in Poets’ Corner, Westminster Abbey, close by the burial remains of such literary giants as Chaucer, Spenser, Dryden, Addison, Johnson, Dickens, Tennyson and Kipling, and in company with the memorial markers of great men and women of letters from Caedmon to Ted Hughes.

Lewis belongs in Poets’ Corner if only because he vastly outranked his contemporaries in intimate knowledge of the medieval and Renaissance poets interred or remembered there; there could be no better tour guide to the forgotten corners of Poets’ Corner. By his own admission, he was an indifferent poet; his best poetry is instead to be found in his colloquial philosophical prose, his mythopoeic fiction, his vernacular theology and his scholarship in the service of poetry—in A Preface to Paradise Lost as much as Perelandra, in English Literature in the Sixteenth Century as much as The Voyage of the Dawn Treader.

It is all of a piece. To assess Lewis’s contribution to English letters and world culture, we must consider the whole big, humorous and dogmatical man, for as his lifelong friend Owen Barfield put it, “Somehow what he thought about everything was secretly present in what he said about anything.”

What did Lewis think about everything? One answer to that question may be found in The Discarded Image, a collection of essays based upon his university lectures on medieval and Renaissance poetry, published in the year after his death. The “image” Lewis had in mind—he also called it the “medieval model”—is a comprehensive vision of the universe as an ordered whole filled with meaning, knit together by an inner telos, and of the human person as a rational creature made in the image and likeness of God, fallen and redeemed. No achievement of genuine science can render the essential features of this vision obsolete; but once discarded, it can be recovered only by a heroic effort of imagination and reason.

And it is here that Lewis’s greatness lies. Though surpassed in poetic diction by T. S. Eliot, in prose style by Virginia Woolf, in theology by Karl Barth, in philosophy by Elizabeth Anscombe, he made the effort that was most needed; he gave us back the discarded image. No reactionary antimodernist, Lewis was master of the fine art of ressourcement—revitalizing the present by reclaiming the past. In every field he entered, his mission was recovery.

As a literary scholar he rehabilitated (against what he called the “vigilant school” of academic criticism) the reputation of Spenser and Milton, the allegorical tradition, and the intrinsic value of literary experience.

As a writer of fantasy fiction, he made the other worlds of our solar system and the invented world of Narnia a stage where myths are real and souls are won or lost. As a satirist, in works like The Screwtape Letters, The Great Divorce and That Hideous Strength, he translated the classical syllabus of virtues and vices into a moral psychology capable of confronting modern ambiguities and evasions.

As a Christian philosopher, he advocated for moral realism by an appeal to common sense, defended the miraculous by an appeal to reason and unfolded—after the fashion of St. Augustine—the perennial dialectic of desire.

C. S. Lewis is our Augustine, not redivivus but reinvented for the needs and aptitudes of a time when knowledge of the past is receding and hope for the future is at risk. We honor his memory best when we keep the image he recovered for us fully in play.