Flea market capitalists: Disaffected and disenchanted

You probably spent time in the past year talking about large national, even global, issues. Though you know that millions of people vote in elections, you still assume that your voice and your vote matter. You are probably a member or a leader of several institutions—family, congregation, professional group, civic organization, school. You may have engaged in some way with a governmental body at the local, state or federal level. To a large extent, your participation in this interwoven social fabric defines who you are. When you think about your vocation or when you dream of changing the world—whether locally or globally—you think in terms of these social units.

Tens of millions of Americans do not live or think this way. They see themselves as isolated individuals struggling in a forbidding environment. They may be close to a few family members or friends, but they do not see themselves as belonging to any community, certainly not any community marked out by a government and usually not any congregation or civic group either. They experience institutions as centers of power and control that do things to them, not for them or with them.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Often, they view their lonely individualism as a heroic choice. If institutional power is outside their control, then the best strategy, they have concluded, is to keep those institutions from controlling them, to whatever degree possible. This, for them, is the meaning of freedom. Freedom does not mean doing whatever one wants—that takes power and money. Freedom means making a few private, personal choices in a context mostly determined by others.

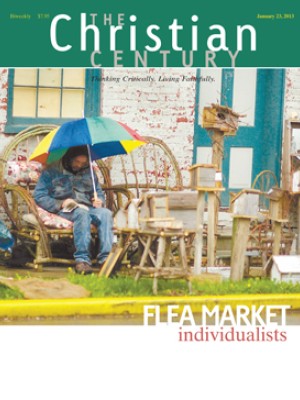

For the past six years, I have been thinking and writing about the people who view the world this way and who struggle to lessen the grip of institutions on their lives. I’ve focused my research on flea market dealers in central and southern Indiana. Flea market dealers are not a huge group, but they are the leading edge of a much larger population of people who are disaffected and disconnected from the web of institutions many of us take for granted.

On a professional level, this topic was a huge departure for me. For 25 years, I studied religious organizations and how they have responded to cultural and social change. As a scholar, I knew that the percentage of people who say “unaffiliated” or “none” when asked about their religious affiliation has risen steadily for a few decades. I’ve given some thought to the tension between individualism and commitment in American life.

And I was always interested in the people who stood outside institutions. I’d attended flea markets for decades and been curious about the radical individualism of my flea market friends. Besides, I come from southern Indiana, and I’ve got a libertarian streak of my own.

When I started my project, I wondered whether the rebel attitude of the flea market dealers was rooted, like my own views, in a libertarian philosophy. For some of them, it is. But what I mostly found among dealers was a near-total disaffection from and disenchantment with the institutions of business, religion and government. This stance is all the more intriguing given that these folks describe themselves as hard-working capitalists, faithful believers in God and die-hard patriots.

The dealers really are capitalists. They buy and sell entirely subject to the laws of supply and demand. For the most part, they are free from bosses. They are also free from payroll taxes, from Social Security and from having to wear proper business attire. Men can wear their hair long, women can wear jeans, and they run their very small businesses as they see fit.

At the same time, their incomes vary substantially from week to week, they have no benefits and no collective means to bargain for better wages or working conditions. Nothing keeps the person three booths down from offering the same goods at a discount at any moment.

If this seems a poor trade-off for the dealers, it is important to remember that most of them did not choose their economic status from a large menu of better options. Some dealers live on disability checks, and their flea market business provides a little extra money off the books. Some were fired or laid off or simply could not stand the thought of going to work one more morning. In nearly every case, the dealers were what Marx would call “alienated” workers. In their former jobs, they had no connection to the things they produced or the means of producing them. They did what they were told, got paid and lived their “real” lives away from the workplace.

Many of the dealers have bad things to say about bosses, by which they generally mean mid-level managers. I assumed dealers would also dislike lawyers, but it turns out complaining about lawyers is a middle-class phenomenon. Instead, the dealers focus their distrust on bankers. They even distrust tellers and managers at bank branches. I heard many stories of people losing their bank accounts or being charged extortionate fees or being denied access to their funds. Many dealers keep all their money in cash (not that many of them have much to keep).

These dealers do not believe that unions, new political leaders or more progressive policies will improve their position. As Charlie Daniels sings, “They ain’t asking nobody for nothing, if they can’t get it on their own.” Expecting nothing from the system, they try to make sure that representatives of the system—bankers, tax collectors, health officials, government agencies—do not take anything from them.

Are their economic prospects primarily determined by large, impersonal, even global forces beyond their control? Of course. So are yours and mine. The difference is that the dealers have no mediating institutions to buffer them and no hope that family, church or state will protect them from these forces. They protect themselves by withdrawing as far as they can.

Do they believe anything buffers or shelters them? Yes—God.

Their belief in God was especially striking to me, because I chose not to interview anyone who had attended church more than twice in the past year. (Remember, I was looking for the least institutional folks I could find.) All but two of my 60 respondents expressed a deep, certain faith in God. Despite their circumstances, they believe that God cares for “little people” like them.

Except for a couple of recovering alcoholics, this group did not express a general belief in a Higher Power. No, they believe in the God of Abraham, Moses and Jesus. They believe that scripture is inerrant and that Adam and Eve were real people. They believe in Jesus’ miracles, bodily resurrection, second coming. If faith means belief, then these people really have faith. On the other hand, if faith means discipline, immersion in sacred texts, participation in a faith community and development of a set of character traits, then these people don’t have much faith.

The dealers believe that God looks out for them in personal, specific, magical ways. One told me about how a dead loved one spoke to him through an eagle while he was on a lake fishing. Another interpreted very detailed dreams as messages from God. I heard stories, very earnestly told, of mysterious strangers showing up with money or help in times of need. These beliefs are real.

So too are beliefs about the Bible’s literal, historical, scientific truth. The dealers regard the creation stories as literal history. And why not? The intellectual alternative has no traction for people not socialized into accepting the scientific method. The dealers believe that Jesus performed miracles and was raised from the dead. And why not? Their parents and grandparents believed these things and, more to the point, a world in which God could not do this is too painful for them to imagine. If God helps little people like them, why couldn’t God resurrect his own Son?

Because the dealers believe so strongly in God and hold a literal view of scripture, pollsters would probably lump them with evangelicals. But they are not evangelicals. They fight off the “born again” label. They do not go to church. They do not watch evangelical television programs. They do not know who Rick Warren is, and they have never read any of the Left Behind books.

Once again, the role (or absence of a role) of institutions is critical to their identity. Evangelicalism is an institutional movement grounded in congregations, parachurch organizations, books and media. The dealers are far removed from any of that. They see churches, especially pastors, as representing one more set of people who want to take their money and tell them what to do. In contemporary parlance, they occupy their own little corner of the category “spiritual but not religious.”

These are capitalists who distrust business, believers who distrust religion, and patriots who distrust government. “I Love My Country But Fear My Government,” says a pertinent bumper sticker. They are not Occupiers and they are not Tea Partiers, NASCAR Dads or even Republicans. Of course, they are not Democrats either. They do not oppose expansion of government on the principle that free markets are preferable. Rather, they believe government is primarily an oligarchy that works for people who already have power and money. Government is not something they are part of; it is something that does things to them.

Contemporary political debates only push the disaffected dealers further into isolation. Until the late 20th century, it was possible to discuss the expansion of the federal bureaucratic state in the context of other ways of making collective decisions, such as via families, congregations, neighborhoods, unions, social service groups, town governments and state governments. Today, the ideological choice seems limited to expanded federal programs on the one hand or total unalloyed individualism on the other. For every conservative calling a Democrat a “socialist,” there is a liberal calling a Republican a “social Darwinist.”

If those are the choices—either government as surrogate community or every man for himself—what can the dealers possibly do? Should they put their faith in a powerful bureaucratic state run by people who are manifestly not them, or should they fend for themselves in a globalizing, corporate, bureaucratic economy run by people who are not them either? Faced with that choice, they drop out.

Their political opinions cross over the standard boundaries. Media attention to homosexuality over the past couple of decades makes them uncomfortable, but the majority of them say, “I wouldn’t want to tell someone else how to live their life.” They do indeed cling to their guns, which fits their strategy of insulation and isolation. A gun represents the ultimate ability to say no to coercion. Guns are about freedom—again, not the freedom to do whatever you want, but the freedom from being forced to do what you do not want. Abortion? Most are strongly against it but add, “I wouldn’t want to tell anyone else what to do.”

The dealers are not Occupiers, Tea Partiers or libertarians, though they share with those groups a disillusionment with “the system.” They might be drawn in by a charismatic populist politician—I spoke to some who admire Ross Perot or Jesse Ventura—but they don’t share the specific goals of Occupiers and Tea Partiers, and they don’t share the self-conscious philosophy of libertarians.

It might be expected that at this point in my account I should turn to solutions. How might this population be engaged? Progressives might say they need to get more involved in the political process. Conservatives might say they need to be involved in stronger mediating institutions—in families, congregations and service groups.

Disaffection is not going to be repaired by politicians, business leaders or pastors trying harder. Over the decades the modern West has built a consumer society in which people get more personal choices and lifestyle freedom in exchange for a loss of community, tradition and stability. We are still interdependent, of course, but the connections are complex, malleable, idiosyncratic.

Some people still live in tight-knit communities; others are lucky enough to have the education and money needed to pursue their “lifestyle choices.” But the people at the bottom have limited choices, and some choose to be left alone. Flea market dealers are an extreme example of this segment, but poor and lower working class people all across America have tenuous relationships to the institutions of family, school, business and government.

A recent Pew study confirmed the rising number of people who claim “no religious affiliation.” People are also increasingly choosing “no political affiliation.” (Many people who say they are politically independent reliably vote conservative or liberal, but this only proves the point—they have opinions but resist membership commitments.) If people could choose “no economic affiliation,” many would probably do that too.

But sheer economic necessity means that most people cannot make that choice. Withdrawing from religious or political institutions is far easier than withdrawing from economic ones. Disenchantment and disaffection are widespread, but most of us have too much to lose to chuck it all to sell socks at a flea market.