Visions of Zion: Changes in Mormon social ethics

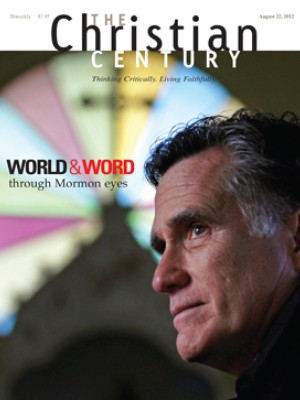

In February Mitt Romney made two of his more memorable campaign trail gaffes, both regarding wealth. Speaking to CNN about the economy after his important win in the Florida primary, Romney said he was “not concerned about the very poor.” In context, Romney was actually expressing concern about the economic prospects of middle-class Americans “who right now are really struggling”; in the same breath, he admitted being not overly worried about the “very rich,” who are “doing just fine.” But the damage was done. The image of Romney as an out-of-touch multimillionaire was only reinforced later that month when he told a group in Detroit that his wife “drives a couple of Cadillacs.”

Other reports have examined Romney’s tenure as a Mormon bishop, the leading ecclesiastical office in a local congregation, or ward. Except at the very highest echelons, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormon or LDS Church) is administered by lay volunteers, who add labor for the church to their ordinary responsibilities of work and family and service in the community. Romney served as a bishop and then stake president in the Boston area while working full-time at Bain Capital and helping to raise his family. Numerous stories from this period reveal him as a compassionate leader who gave considerable time and attention to the poor and downtrodden, who was frequently one of the first on the scene when tragedy struck, and who often donated his own money to families in need.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Romney’s Mormonism often grabs headlines, but it is a mistake to look for distinctively Mormon sources of every aspect of Romney’s personality or politics. His open and deep commitment to the LDS Church should be counted as only one of many formative influences. Yet the intense spotlight shining on Romney invariably raises questions about his faith. For instance, what has Romney learned about social issues from his lifelong affiliation with the LDS Church? Setting Romney’s personal convictions aside, what is the Mormon social ethic, if there is one? Is Mormonism concerned about social issues or is it oriented primarily toward the preaching of the gospel and the salvation of souls?

It is impossible to generalize about the social ethics of Mormons in the aggregate, since they, like every other group of believers, fall all over the ideological and political map. Mormons in California were decisive in passing Proposition 8 to ban same-sex marriage, but in recent months some Mormons (in admittedly small numbers) have openly marched in gay pride parades across the country.

We can begin to get at the issue by focusing on the authoritative teachings of the LDS Church’s scriptures and pronouncements from its leading prophets and apostles, recognizing that individual Mormons have always interpreted and selectively applied official church teaching according to their own circumstances and convictions. With a few notable exceptions, the church hierarchy has encouraged members to follow their own conscience on social matters, according to the spirit of founding prophet Joseph Smith’s oft-cited dictum: “I teach them correct principles and they govern themselves.”

The distinctive social vision of Mormonism can be captured in one word: Zion. In the LDS Church’s two canonized collections of revelations to Joseph Smith, known as the Doctrine and Covenants and the Pearl of Great Price, Zion appears over 200 times, more than in the entire Bible. In his “inspired” retranslation of the Bible, Smith significantly expanded on the cryptic passing reference to Enoch in Genesis 5:24: “And Enoch walked with God: and he was not; for God took him.” In Smith’s hands, this one verse exploded into a long chapter that included a grand theophany. The story is not just about Enoch’s relationship with God but about his city, called Zion, which was taken up to heaven with him. Mormons frequently quote the scripture’s description of this ideal society: “And the Lord called his people Zion, because they were of one heart and one mind, and dwelt in righteousness, and there was no poor among them” (Moses 7:18, Pearl of Great Price).

Smith and his successor, Brigham Young, engaged not just in religion-making but in world-making. They sought to create a new godly society—Zion—that would encompass every aspect of life: spiritual, political, economic and social. According to Smith’s revelations, in Zion the Saints (as they were called) would economically hold all things in common, as did the early Christians as chronicled in Acts. Because Zion was a community of Saints, it would be predicated on bonds of love, trust, benevolence and righteousness, with any quarrels mediated by church rather than civil authorities.

As their name indicated, the Latter-day Saints strongly believed that the second coming of Jesus was imminent and that their role was to gather the elect out of the surrounding “Babylon” and bring them to Zion, which would be “a land of peace, a city of refuge, a place of safety for the saints of the Most High God.” Providing a harbor from the violence and corruption of the last days, Zion would be a cosmopolitan community of peace—the righteous “shall be gathered unto it out of every nation under heaven; and it shall be the only people that shall not be at war one with another” (Doctrine and Covenants 45:66, 69). In short, the Mormon ideal of Zion is a utopian community where righteousness reigns and all forms of evil and inequality are rooted out. There is no war, no poverty and no distinctions between the people, as “all are alike unto God” (2 Nephi 26:33, Book of Mormon).

The 19th-century Mormon kingdom always featured a strong degree of individual responsibility and accountability, but the emphasis was on the community and the common good. As Mormonism developed in the late 19th and early 20th century, the church dropped many of its overtly communitarian practices and shifted toward making personal morality the mark of saintliness. In broad terms, the church followed the same path as many conservative Protestant denominations in reacting against the Social Gospel. It is common for many Mormons today to downplay the radically countercultural aspects of Smith’s vision of a Zion characterized by peace and social justice and to emphasize instead another, more individualistic definition in the Doctrine and Covenants, where Zion is “the pure in heart” (97:21).

By the latter half of the 20th century, the orientation toward individual morality was Mormonism’s dominant theme. In a 1947 letter to a prominent liberal Mormon academic, the church’s First Presidency asserted that “the social side of the Restored Gospel is only an incident of it; it is not the end thereof.” (The letter went on to uphold the church’s policy, not rescinded until 1978, that those of African descent could not be ordained to the priesthood or enter the church’s temples.)

One of the principal opponents of liberal theology and a liberal social ethic in late 20th-century Mormonism was Ezra Taft Benson, a former member of the Eisenhower cabinet who was also one of the church’s 12 apostles for more than four decades before becoming president of the church in 1985. Shortly before becoming president, Benson taught the members of the church: “The Lord works from the inside out. The world works from the outside in. The world would take people out of the slums. Christ takes the slums out of people, and then they take themselves out of the slums. The world would mold men by changing their environment. Christ changes men, who then change their environment. The world would shape human behavior, but Christ can change human nature” (from Benson’s “Born of God” speech at the church’s October 1985 General Conference). Still extensively quoted in LDS Church curriculum materials, Benson drew a line in the sand which, by clear implication, left not only the policies of the welfare state but also a religiously oriented social ethic on the wrong side of the line.

Statements such as these from church leaders have discouraged, if not entirely squelched, the development of a pronounced social ethic in contemporary Mormonism and have focused attention on individual action rather than structural analysis. This emphasis has deep implications for social and political action, but its foundations are more theological than ideological.

Sin and redemption are primarily individual affairs in contemporary Mormonism. Joseph Smith’s revelations fiercely denounced the notion of original sin, and Mormon children memorize one of the religion’s articles of faith: “We believe that man will be punished for his own sins, and not for Adam’s transgression.” Accordingly, the libertarian-leaning politics of Ezra Taft Benson—and the majority of modern Mormons—is rooted in the felt need to protect at all costs the freedom of the individual, which is often called “free agency” or “moral agency” in Mormon parlance.

For Mormons, current ideological battles are a continuation of the cosmic struggle between Jesus Christ and Satan that took place in the “war in heaven” before the earth was formed, in which Satan sought to enslave the children of God and Christ guaranteed their freedom as moral agents. Indeed, it remains quite common for Mormons today to cite free agency and the war in heaven as the foundations of their political philosophy.

Mormons are widely known as good people who live upstanding lives of virtue and morality—though the flip side of this reputation for rectitude has been accusations of clannishness and self-righteousness. Yet since the 1930s Mormons have also been nationally and internationally recognized for expending substantial resources in “taking care of their own” through the church’s welfare program, originally set up as an alternative (and ideological competitor) to the New Deal. Particularly in recent decades, the welfare program, which focuses primarily on members of the church, has been complemented by the rapid expansion of the church’s humanitarian services program, which has been lauded as one of the most efficient and effective faith-based relief and development efforts in the world, especially given the church’s relatively modest size. According to the church’s website, in 2010 it provided relief to people affected by 119 disasters in 58 countries.

This social action is motivated by deep religious commitments. The front page of the church’s website for humanitarian efforts cites Jesus’ admonition: “Verily I say unto you, inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me” (Matt. 25:40). Recently the church quietly but officially declared helping the poor and needy to be a central focus in bringing people to Christ.

This is not an innovation so much as a renewed emphasis of a foundational principle. Joseph Smith’s and Brigham Young’s vision of Zion had a strong element of wealth redistribution, administered by the church and entered into voluntarily by covenant on the part of individual members. For instance, church leaders under Young issued an “Apostolic Circular on the Economy” in 1875 that connected liberty with the equal distribution of wealth and roundly condemned the “wonderful growth of wealth in the hands of a comparatively few individuals.” The proposed remedy was a program of economic cooperation that the Mormons had been struggling to implement and preserve in pioneer Utah. This collectivist system was based in part on one of Smith’s early revelations, sometimes called the “Law of the Church,” which stated: “And behold, thou wilt remember the poor, and consecrate of thy properties for their support, that which thou has to impart unto them, with a covenant and a deed which cannot be broken. And inasmuch as ye impart of your substance unto the poor, ye will do it unto me” (Doctrine and Covenants 42:30–31).

Mormons are fond of quoting Joseph Smith’s statement that “a man filled with the love of God is not content with blessing his family alone, but ranges through the whole world, anxious to bless the whole human race.” Smith was not advocating a program of transformative social change—or even economic relief and development. Rather, he was cheering on the church’s early apostles who were in England on a traditional evangelizing mission.

In the view of the majority of contemporary Mormons, welfare and humanitarianism are essential work for the individual Christian and the collective church, but the priority is always salvation in both individual and family contexts. The church’s remarkable recent investment in education for its international members, called the Perpetual Education Fund, is administered locally and focuses on the acquisition of mostly vocational skills in an effort to help individuals and families lift themselves out of generations of poverty and equip them to take on greater leadership in local congregations. Social welfare thus contributes to the advancement of the kingdom of God. Brigham Young is said to have quipped, “You can’t teach a starving man the gospel”—but most Mormons believe that the world will be transformed on the level of individuals and families, not by large-scale social planning. Individual righteousness and charity lead to Zion, not vice versa.

Similar foundational theological commitments underlie a Mormon ethic of war and peace. The Bible traces the origins of deadly violence to the first sibling rivalry between Cain and Abel. Joseph Smith’s revelations placed the origins of conflict even earlier, with the premortal “war in heaven” between the followers of Jesus and those of Satan. Like the Bible, the Book of Mormon is a bloody text, beginning with threats of murder, attempted fratricide and a divinely inspired decapitation, culminating in not one but two civilizational holocausts. The Book of Mormon also has a strong subtext of Christian nonviolence, however, and a number of Mormon scholars have argued that the book is actually something of a pacifist manifesto. Some of Joseph Smith’s revelations canonized in the Doctrine and Covenants are equally if not more explicit. In one 1833 revelation which calls itself an “immutable covenant,” the Latter-day Saints are commanded by God to “renounce war and proclaim peace” (Doctrine and Covenants 98:16).

The violent persecution of Mormons, particularly in Missouri in the 1830s, led the Latter-day Saints to adopt a stance of self-defensive violence. The aforementioned 1833 revelation did allow for limited, direct self-defense, but its clearly stated preference—even in the face of unrelenting hostilities and innocent suffering—was always for a vigorous Christian ethic of forgiveness and reconciliation. Early Mormon revelations never called upon the Saints to commit violence nor gave them license to do so of their own accord, yet they felt that pragmatic necessity—even their very survival—required them to take up arms for their own protection.

This logic of justified self-defense occasionally exploded into acts of unconscionable violence, most notably the 1857 Mountain Meadows massacre in which Mormon settlers in southern Utah planned and carried out the cold-blooded murder of approximately 120 California-bound emigrants. But for the most part 19th-century Mormons sought peace with their neighbors, and in fact were often eyed warily by other western settlers who thought they were too friendly with local Native Americans.

Mormons generally remained on the sidelines in America’s 19th-century wars; many saw the Civil War as God’s vengeance on the nation for the persecution of the Saints and the murder of Joseph Smith. But as part of the rapprochement between the United States and the LDS Church that commenced in the 1890s, the church sent its sons to fight in the Spanish-American War as a token of its patriotism and loyalty to the country—a pattern that has been followed ever since. Speaking broadly, in the past century Mormons have been inclined to support their nations’ wars as legitimate and perhaps the most effective means of resolving international disputes, both as a general principle but especially when involving their home country. Though Latter-day Saints would certainly always prefer peace to war, as a group they are somewhat dubious about the efficacy of nonviolent alternatives ranging from pacifism to conscientious objection to robust internationalism. Relatively little research has been done on the attitudes and behaviors of Mormons outside the United States (who now constitute the numerical majority), but at least in the U.S., Mormons serve in disproportionate numbers in the armed forces and national security apparatus. LDS Church leaders publicly supported every major American war in the 20th and 21st centuries, which has correlated with (and perhaps caused) a markedly high level of support for war among the general Mormon public.

On the other hand, a small but growing community of Mormons finds in their scriptures, prophetic teachings, history and culture a powerful warrant for peace. Many invoke a strongly Christocentric reading of scripture that draws upon biblical interpretations from non-Mormon scholars such as René Girard and John Howard Yoder. They also point to a poignant story in the Book of Mormon in which a group of new converts who had previously made war against the believers feel convicted of their sins and decide to literally bury their weapons of war in the ground. When they are in turn marched upon, they come out to greet the invaders armed with nothing more than prayer. Over 1,000 are slaughtered, but even more of the aggressors are pricked in their conscience and decide to lay down their weapons and join the church of God because of the example of these Christian pacifists.

Contemporary Mormon pacifists also invoke the bold teaching of president and prophet Spencer W. Kimball, who, in an issue of the church’s official magazine celebrating America’s bicentennial in 1976, railed against the “false gods,” including wealth and militarism, which he said the Latter-day Saints too often worshiped. Wrote Kimball: “We are a warlike people, easily distracted from our assignment of preparing for the coming of the Lord. When enemies rise up, we commit vast resources to the fabrication of gods of stone and steel—ships, planes, missiles, fortifications—and depend on them for protection and deliverance. When threatened, we align ourselves against the enemy instead of aligning ourselves with the kingdom of God. . . . Our assignment is positive: . . . to carry the gospel to our enemies, that they might no longer be our enemies.”

The struggle between national particularism and gospel universalism has also recently been on display in debates over immigration policy. Aligning with other political conservatives, a number of Mormons have taken strong stands against illegal immigration. One prominent Mormon voice on the subject is Russell Pearce, the Arizona state senator who sponsored the controversial anti-illegal alien measure SB 1070 (and who subsequently became the first state lawmaker in Arizona history to be removed from office via a recall election).

Yet the LDS Church surprised many in 2011 when it publicly supported the Utah Compact, widely hailed as a sensible, moderate approach to immigration that acknowledged the economic and other contributions of immigrants in American culture and history and strongly opposed any policies that would unnecessarily separate families. Many observers have noted that the hardline immigration policies of Pearce and to a lesser degree Mitt Romney put them in conflict with the official stated position of their church.

The widely noted Mormon commitment to the nuclear family may have won acclaim from political moderates and liberals when it came to immigration policy, but it has also provided the impetus for the LDS Church’s opposition to same-sex marriage, most famously in the church’s mobilization in favor of California’s Proposition 8. While publicly supporting a wide range of civil rights for the LGBT community, the church that once went to the Supreme Court on behalf of its own expanded definition of marriage has unequivocally rejected the extension of marriage to same-sex couples.

If individual moral agency is one cornerstone of Mormon social ethics, then the centrality of the family is another. In a 1995 proclamation to the world, the church leadership taught “that marriage between a man and a woman is ordained of God and that the family is central to the Creator’s plan for the eternal destiny of His children.” The proclamation went on to affirm the eternal nature of gender, the continuing importance of complete fidelity within marriage and sexual abstinence without, the maximization of human happiness and purpose within families, and the accountability of individuals, communities and nations before God for upholding family-centered principles and policies. Mormons are almost universally conservative on sexual ethics, though they may disagree about how those ethics are best mediated and translated into laws in a pluralistic public sphere.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is exceptionally good at teaching personal morality, and it expends a considerable portion of its time and other resources in encouraging its members to pursue lives of individual integrity and moral rectitude. As a bishop and then stake president, Mitt Romney would have spent countless hours working with the unemployed and others in need of church welfare assistance; providing marriage counseling; organizing activities for children and teenagers that encouraged them to live the gospel principles of chastity, temperance, honesty and hard work; planning weekly worship services designed to meet the diverse needs of a congregation of several hundred people; training other members to succeed in their respective church assignments; stewarding the congregation’s finances; administering priesthood blessings of healing and comfort; coordinating missionary work and encouraging temple attendance; and countless other responsibilities aimed at the spiritual and moral uplift of his flock.

Even if Romney had had the inclination, he would have had little time to run a soup kitchen, march against war or lobby Congress on the pressing social issues of the day. Members of his congregation may well have done all those things—with his blessing. For the LDS Church’s priesthood leadership, however, social action beyond the bounds of the congregation simply is not a major part of the job description.

It is common for Mormons to sneer at what they see as an increasingly degenerate world in which the Ten Commandments have become, at best, suggestions. Considerably less time and attention is paid in mainstream Mormon circles to social ethics than to individual morality. No doubt the theological and cultural resources exist within Mormonism for a more robust social ethic to develop, but for at least the past century the church’s emphasis has been on personal righteousness and family togetherness, not on social welfare as a whole. It is perhaps telling that the first scriptural reference in the entry on “Ethics” in the quasi-official Encyclopedia of Mormonism refers to 1 Peter 1:15–16: “Instead, as he who called you is holy, be holy yourselves in all your conduct; for it is written: ‘You shall be holy, for I am holy’” (NRSV). The longing for Zion has by no means been erased in modern Mormonism, but for better or worse the radical, socially transformative vision of Joseph Smith and Brigham Young has been thoroughly domesticated.