The end of impunity? The International Criminal Court issues a verdict: The International Criminal Court issues a verdict

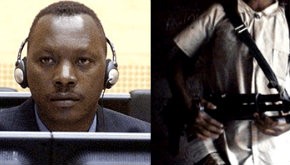

Ten years after it was founded, the International Criminal Court has issued its first decision. On March 14, the ICC—the world’s first permanent tribunal with jurisdiction over war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide—found Congolese warlord Thomas Lubanga guilty of recruiting and enlisting child soldiers. He forced children as young as 11 to pick up guns and aid in ethnic cleansing in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2002–2003.

The landmark decision has been hailed as a victory for the protection of children in armed conflict and praised for its strong message to perpetrators that violations of international law will no longer go unpunished. Estonian diplomat Tiina Intelmann, the president of the Assembly of States Parties which established the ICC, declared, “We have left the age of impunity behind us and entered the age of accountability.”

For the past half-century, human rights advocates have struggled to find adequate mechanisms to punish the most serious crimes of international concern. National courts are supposed to enforce the Geneva Conventions and other humanitarian laws, but these courts are often unable or unwilling to prosecute crimes committed by high-ranking state officials. To combat impunity in these settings, the international community has periodically established ad hoc tribunals. In the aftermath of World War II, the Allied Powers set up tribunals at Nuremberg and Tokyo to prosecute Nazi and Japanese war criminals. More recently, the United Nations Security Council created international tribunals to address crimes committed in Rwanda, the former Yugoslavia and Sierra Leone. It was the Special Court for Sierra Leone that in May sentenced former Liberian president Charles Taylor to 50 years in prison.