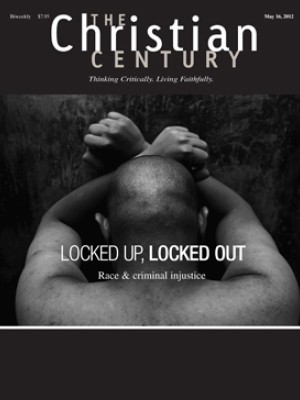

Criminal injustice: Michelle Alexander on racism and incarceration

In her 2010 book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, civil rights lawyer Michelle Alexander examines the practices and policies that have quintupled the U.S. prison population over the past 40 years. She argues that these policies have created a permanent underclass of disenfranchised convicted felons who are overwhelmingly black and Latino. Alexander has worked for the American Civil Liberties Union and was a clerk for Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun. She teaches at the Moritz College of Law at Ohio State University.

How did you begin your research into the patterns of racial discrimination and social control that you call the “new Jim Crow”?

I was inspired by my experience working as director of the Racial Justice Project for the ACLU in California. I was representing victims of racial profiling and police brutality and investigating patterns of drug enforcement in poor communities of color. I was also working with people who were being released from prison to reenter a society that had never had much use for them. I awakened to the reality that our criminal justice system functions more as a system for racial control than as a system for crime prevention. I found out that what I thought I knew about the criminal justice system—and I thought I knew quite a bit; I was a lawyer, after all—was sheer myth.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

I believed, for example, that the explosion in our prison population could be explained primarily by poverty, poor schools and broken homes—conventional explanations offered by the media and mainstream politicians. Back then I thought that blacks were more likely to use and sell illegal drugs than whites. I thought that the War on Drugs was aimed primarily at rooting out violent offenders and drug kingpins. I also believed that although life might be difficult for people after they are released from prison, those who worked hard and had self-discipline could make it.

I came to realize that the explosion in our prison population, especially the explosion in the number of blacks in prison, is not driven by crime or crime rates. People of all colors use and sell illegal drugs at the same rates. The War on Drugs does not root out violent offenders. On the contrary, the people who come into the criminal justice system through the drug war are not violent and are arrested on relatively minor drug offenses—the same kinds of offenses that occur frequently in middle-class white communities and are largely ignored.

Those released from prison are trapped in a legal second-class status for life. Finding work is not just difficult after prison; it is downright impossible. Ex-offenders are locked out of the legal economy. They are denied access to public housing; they are denied food stamps. And to make matters worse, they are saddled with hundreds of thousands of dollars in fees, fines, court costs—and often the need to pay back child support. Paying all of these fees can be a condition of parole.

I came to see that we have, yet again, created a vast new legal system for racial and social control, a penal system unprecedented in world history—a system that locks the majority of black men in many urban areas into a permanent underclass status. And yet we claim, as a nation, to be colorblind.

What made this system of social control possible?

The system of mass incarceration was born out of our nation’s racially divisive politics. The War on Drugs was part of the Republican Party’s “southern strategy.” That strategy used racially coded “get tough” language on issues of crime and welfare to appeal to poor and working-class whites, especially in the South where whites were anxious about the gains made by African Americans in the civil rights movement. When President Ronald Reagan declared his War on Drugs, it was an effort to make good on campaign promises to get tough on crime. Subtly, the enemy in the war became racially defined.

The courts rallied to facilitate the War on Drugs by eviscerating Fourth Amendment protections against unwarranted searches and seizures and by closing the courthouse doors to claims of racial bias at every stage in the criminal justice process, from searches to sentencing.

Legislators began to compete with each other over who could be tougher on crime. Democrats and Republicans alike began supporting harsh new mandatory minimum sentences for minor drug offenses, sentences even harsher than murderers receive in other Western democracies.

At its core, this system is supported by a deliberate indifference to people who are thought of as the other, people living in ghettoized communities, people who we consciously and perhaps even more often unconsciously imagine to be no good, not worthy of our care and concern, to be largely disposable, to be beyond redemption. Unconsciously willing to believe the worst possible things about “those people,” we’ve been able to turn a blind eye as we’ve passed these laws and ushered people into a permanent underclass.

How is colorblindness a problem?

People typically think of colorblindness as a virtue; to say “I don’t care if he is black” is considered a good thing. But it can also be a form of cruelty. It can be a way of being indifferent to the experiences of racial groups.

Colorblindness can be a way of dismissing an important dimension of a person’s experience and the experience of a community. This blindness and indifference allow many of us to turn away from those who are desperately in need of our care, compassion and concern.

What role has the privatization of prisons played?

Mass incarceration was not the result of a profit motive. It was born out of our nation’s racial divisions and anxieties. But once the race to increase incarceration began, it quickly became apparent to corporations and to a range of private interests that profits could be made from caging human beings. Private prison companies were born, and they are doing quite well on the New York Stock Exchange in a time of economic recession.

Some companies now use prison labor rather than send jobs overseas. They can use prison labor because even though the 13th Amendment abolishes slavery, it makes an exception for forced labor in prison. These companies can avoid minimum wage laws and the usual costs of labor.

There are corporate interests, like phone companies, that charge exorbitant costs for services to prisoners and their families. Private health-care companies do a great business through their contracts with prisons, though they usually provide substandard care to people behind bars. There are also the Taser gun manufacturers.

We also have to consider public organizations like prison guard unions. Those groups don’t just lobby for higher wages and better working conditions; they lobby for harsh mandatory minimum sentences that provide job security. There are entire communities—mostly rural and white—whose economic growth and stability are based on prisons. Most new construction of prisons has been in these communities. Although prisons are often advertised as providing far more benefits to their communities than they actually deliver, the reality is that many of these communities now view prisons as essential to their economic health.

How do we make sense of the fact that it is cheaper to pay for four years of tuition to Princeton University than to incarcerate someone, and yet we are willing over and over again to pay this exorbitant social and financial cost?

It was not a rational policy debate that led to the decision that we would incarcerate 2.5 million Americans and place another 7 million under correctional control. It was a system developed by emotionally and racially charged politics that are misinformed. The system we have is a reflection of our divisions, our anxieties, our social impulses, our conscious and unconscious racial biases.

We’ve known for decades that it is far cheaper to invest in education than incarceration. The billions of dollars for incarceration would be better spent on sending young people to good schools and colleges, rather than locking them up at early ages. Yet we continue to do it.

The New York police department just reported that in the year 2010, officers stopped and frisked 600,000 people; 90 percent of these people were African American and Latino, and less than 15 percent of these stops occurred in response to any sign of criminal activity.

Hundreds and thousands of people—mostly black and Latino young men—are being stopped, searched and frisked as a matter of routine. The data show a virtual police state in some communities that saddles young people with criminal records for having a little weed on them—all but guaranteeing that they will be locked out of the legal economy. Then we wonder why we have a recidivism rate of 70 percent. It is because we have constructed a system that is irrational and counterproductive.

Obviously changes in the legal system are needed, but you say they are woefully insufficient. Why is that?

Many people just focus on the size of the prison population when discussing the question of mass incarceration. For example, they say if we reduce prison sentences, then we can reduce the prison population by a third or a quarter or a half or whatever the target is. But simply changing the length of prison sentences does not in any way dismantle this castelike system. The system depends on the prison label, not just prison time. We could reduce the prison population in half by cutting sentence length, but if people, upon release, still face all of this legal discrimination, they will cycle back in and out of prison. They may stay for a shorter amount of time.

As long as we have a drug war raging, we are going to have people swept into the system at very young ages, usually before they are old enough to vote. They acquire criminal records that will follow them through their whole lives, relegating them to a second-class status by law.

To think about ending mass incarceration, we’ve got to think about much more than reducing the amount of prison time. In my view, that scale of change cannot be just about prison time or about saving state governments money. We’ve got to change an entire mind-set. We’ve got to learn to view poor folks of color, who have been so demonized in recent decades, with the same level of compassion that we extend to people we perceive to be “like us.”

If we were just to return to the incarceration rates of the 1970s, before the War on Drugs and the get-tough movement began, we would have to release four out of five of the people in prison today. A million people employed by the criminal justice system would lose their jobs. To talk in a serious way about ending the system means grappling with its scale. It is going to require a new public consensus that the lives of poor kids in the ’hood are equally valuable as the lives of the kids populating our college campuses.

You’ve said that many strategies of the civil rights era are ineffective in the new regime. Why?

In recent decades, civil rights advocacy moved from the streets and churches to courtrooms and behind-the-scenes negotiations with legislators. We’ve delegated lawyers as spokespeople of the movement, as opposed to community members and faith leaders. This means that the movement is less connected to the communities it claims to represent and has lost its moral authority. For understandable reasons, civil rights lawyers became very invested in affirmative-action programs, which helped a relative few but exacerbated the divisions and tensions between poor and working class along racial lines. Those programs resulted in a sprinkling of people of color attending elite universities and created an illusion of progress. The colorblind rhetoric contributed to all of us being deluded that we are on the road to the Promised Land, when in fact we had already taken a U-turn.

How have people responded to your work?

The biggest surprise to me is that it has been embraced so well by many of the folks that I imagined would resist it. Civil rights organizations, which I criticize pointedly in my book, have embraced it. Maybe it is because I criticize myself as well and acknowledge that I too did not understand the impact of mass incarceration—I wasn’t pointing a finger at others without pointing it at myself. I was as shocked as anyone to realize that there are more African-American people under correctional control today than were enslaved in 1850, that in some states 90 percent of the people sent to prison on drug charges are African American, even though they are no more likely to be guilty of drug-related crimes.

People don’t realize the extent to which ex-felons are excluded from the legal economy. You can’t even get a license to be a barber in my state of Ohio if you have a drug felony on your record. A whole web of laws has been independently justified on the basis of getting tough on crime, but it really does add up to a trap for people. I have been encouraged that when provided with the data and information, many are willing to say, “We do need to make this a higher priority.”

I have also been pleased by the reception in faith communities. The deep irony is that the very folks who ought to be the most sensitive to the demonization of the “despised,” the prisoners, have been complicit and silent.

In my research, I found that many people would say that church was the last place where they would go for help or support or understanding when they got out of prison. It was the place where they felt the most condemned and unwelcome. Pastors would be quick to wave a finger at black men for the way they dressed or for their conduct as fathers. Church was the place where they felt the most shame for their circumstances. As a result, I viewed faith leaders as an important audience for this book. I wanted those people to have a broader understanding of the system and to realize that it wasn’t all about individual choices.

Some have criticized your book for overlooking the experiences of women within the criminal justice system. Is that criticism fair?

The book explicitly focuses on the experiences of black men in the criminal justice system—a system whose prison population is overwhelmingly made up of men. That being said, women are the fastest growing segment of the prison population, and their experiences are as important, and even more disconcerting, than those of men. Women are often the primary caretakers of children, for example. What does it mean for the future of families if more and more women are incarcerated?

But my work on this book was primarily inspired by investigating patterns of law enforcement directed at young black and Latino men. I find in the academic community that when scholars write books about the experience of women in the criminal justice system, no one says, “Well, why didn’t you talk about men?” When you write a book that addresses the unique experience of black men, everyone says, “Well, why didn’t you talk more about women?”

There is a lot more to say about the experiences of women and immigrant groups, a whole host of folks who have been negatively affected by this system. I intended to contribute one piece of the puzzle with the hope of inspiring others to add other pieces.

Do you see seeds of the social movement that you envision?

Absolutely. There are people who have been trying to approach this work from a movement-building perspective for a long time. I am particularly inspired by the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights, a group in Oakland that has conducted youth campaigns to close juvenile prisons in California. These are successful multiethnic, multiracial campaigns for education, not incarceration, with a human rights framework.

I see a potential paradigm shift in faith communities in prison ministries, from primarily viewing prison ministry as a way to save individual souls to viewing it as an opportunity to serve communities and populations in prison and to raise consciousness for collective liberation rather than only individual salvation. I’ve seen a shift in the approach to reentry from providing “job training and pep-talks” to beginning to organize “ban the box” campaigns to end the practice of preventing convicted felons from finding work. Faith groups are showing more of an interest in felon disenfranchisement, shifting away from viewing the problem of criminality as one involving an offender who can’t get his life together to the bigger picture of a systemwide problem.

Many people are turning to the Occupy movement for new forms of political action. Do you see any connection between the kind of social movement you call for and Occupy?

I am so grateful that the Occupy movement burst onto the scene and forced into mainstream discussion the problem of economic inequality and the concentration of wealth and power. That is enormously important. But the 99 percent vs. the 1 percent framing obscures a lot. We are not all situated similarly within that 99 percent. Most of the 99 percent has been willing to turn a blind eye to the predicament of the demonized other. And many in the Occupy movement come from backgrounds in which it has been easy to be ignorant of and indifferent to those who are in ghetto communities or cycling in and out of prisons. That is not a swipe at them. It is a statement of how easy it has been to overlook this system of social control and how disparate our communities can be.

The old Jim Crow system had “Whites Only” signs. Black people were at the back of the bus. It was obvious and undeniable that a system of social control existed designed to deny some people access to resources and equality. But prisons are out of sight and out of mind. People in and out of prisons and enmeshed in poverty are physically separate from the rest of us, from places where there are jobs and a good education system. It is easy to be ignorant and in denial. Consciousness-raising is critically important at this stage.

If you could direct the energies of people who read your book and want to act, what would you urge them to do?

I think the better question might be: What do you feel most inspired to do? What is your sphere of influence? In your faith community, what can you do to raise awareness? You are more likely to get constructive answers that way than by asking. “What is most important to do?”

A great deal depends on what region of the country a group is in. What is the makeup of the group? Some are really fired up to end disenfranchisement laws. Others are outraged that people cannot get access to food. Some simply want to make sure that their particular faith community is really open and welcoming to people who are returning home from prison, setting a tone of welcome.

No matter what a group decides to do, what matters is the way you do it. The need for far-reaching compassion and for a serious understanding of the politics that gave rise to this system is high. We need to paint with a broad brush to get at the magnitude of the problem. We cannot shrink from the hard conversations about race. The way that we go about this work will transform our efforts from piecemeal ones into a larger movement, grounded by a shared commitment to the humanity of us all.