The case against Wall Street: Why the protesters are angry

Read interviews with Gary Dorrien and Shane Claiborne on Occupy Wall Street.

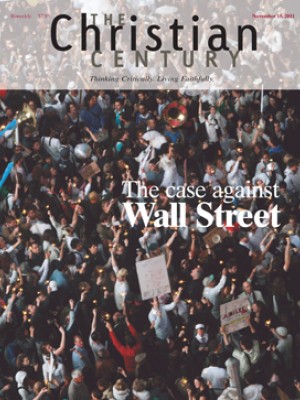

The Occupy Wall Street movement has spread from Lower Manhattan to more than 900 cities and four continents, with major protests occurring in Washington, D.C., Boston, San Francisco, Dallas, Seattle and Phoenix. In some ways it is not the movement that many of us have wanted to see emerge over the past three years—or 30 years. Its organizers are rooted in anarchist theory and strategy; it has no analyses of corporate capitalism or theory of constructive alternatives to it; and thus far it has no demands.

But the conventional activist groups that have demands and agendas have sparked nothing like a movement. Three years—make that 30 years—of stagnant wages and accelerating inequality offered an opening for a populist movement demanding a full-employment economy and a curtailment of Wall Street's speculation and gouging. Now a smattering of mostly youthful protesters has set one off. They would not have succeeded had they operated like conventional trade unions and social justice groups. They are building a social movement that prizes radical democracy, radical hospitality, and a distinct blend of nonviolence and outrage. And the long-term success of Occupy Wall Street depends on its ability to build constructive coalitions with the very groups that initially spurned it.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Since 1982, the share of America's income held by the top 1 percent of the population has more than doubled. Today the top 1 percent of Americans holds 39 percent of the nation's wealth and takes in 25 percent of its annual income. Occupy Wall Street has evoked much ridicule for its central claim about itself: "The one thing we all have in common is that We Are The 99% that will no longer tolerate the greed and corruption of the 1%." But the protesters sleeping in the cold and rain do not claim that 99 percent of Americans agree with them. Their point is that the top 1 percent plays by a different set of rules and has made fantastic gains while everyone else falls behind.

Today, America's superwealthy pay minimal or no income taxes while treating themselves to the capital gains rate—all perfectly legally, owing to the favors that Washington showers on the superwealthy. Investment managers earning billions of dollars per year are allowed to classify their income as carried interest, which is taxed at the same rate as capital gains. Thus, we have a system in which the top 10 percent of the population hold more than 70 percent of the wealth and the bottom 50 percent hold 2 percent of the wealth.

Unemployment is 9 percent officially and twice that figure in reality, with higher rates in African-American communities. The crash of 2008 wiped out $8 trillion of home value. The banks that gambled on the housing bubble they helped create are sitting on $2 trillion in cash, thanks to government bailouts and Federal Reserve easings. President Obama has spent most of his presidency cleaning up an economic disaster, coping with a global credit contraction, trying to appease Wall Street and capitulating to a Republican Party that wants to bust public unions and break America's social contract with the poor and elderly.

All of this, plus the grim fallout for young people seeking a starter job, created the opening for Occupy Wall Street. The unemployment rate for young high school graduates stands at 22 percent and the unemployment rate for college graduates under 25 years of age is 10 percent. Even these figures are lower than reality, because many young people have never entered the system and thus don't get counted, and many others are working in dead-end jobs that bear no relation to their education or training.

Occupy Wall Street began in mid-July with a call from a Canadian activist group, Adbusters, accompanied by an image of a ballerina perched atop Wall Street's iconic charging bull, with riot police appearing in the background. Helped by the online activist groups U.S. Day of Rage and Anonymous, the original protest took place on September 17. The Adbusters ad envisioned 20,000 protesters. Barely 2,000 showed up.

Conventional progressive organizations were leery of the call to occupy Zuccotti Park, just north of the New York Stock Exchange. They also didn't sympathize with how the protest's de facto decision-making group, called the NYC General Assembly, took pride in having no leaders and making no demands. The group explained that it identified with the leaderless revolutionaries of the Arab Spring.

The first few days of the occupation were chaotic and disappointing. The occupying group was small; arrests occurred almost every day; and the number of people actually sleeping in the plaza never exceeded 150. But new people joined every day, some arriving from other cities. The execution of Troy Davis in Georgia catalyzed some people to join the protest, and a breakthrough occurred on Saturday, September 24, when the protesters marched to Union Square. Eighty-seven were arrested, garnering major media coverage, and a movement was launched.

The NYC General Assembly is a group of activists, artists and students involved in the occupation. To the extent that it claims an ideology, it identifies with the anarchist tradition, which shows through mostly in the group's process: egalitarian, autonomous, leaderless, and committed to a modified model of consensus. The organizers were, and are, determined to operate by at least 80 percent consensus, moving as slowly as consensus requires. They have developed a system of hand signals that enhances communication in group settings and have nurtured a powerful sense of community that many occupiers, including many of my students at Union Theological Seminary and Columbia University, have experienced as transformative.

By Day 9 (September 26), the protest was attracting teachers, trade unionists, and many others from traditional activist organizations, and protests in other cities were launched. The issue of demands arose repeatedly as the occupiers worked with their new allies and took questions from the media. Nathan Schneider, an insider to General Assembly discussions, remarked: "The General Assembly is currently in the midst of determining how it will come to consensus about unifying demands. It's a really messy and interesting discussion. But don't hold your breath."

For the occupiers, it is far more important to sustain a spirit of rebellion and to develop a radically democratic movement than to agree on what the government should do about derivatives or tax justice. Occupy Wall Street is not a progressive organization; it is a social movement with a distinct ethos. The organizers understand that making government policy will never be their job anyway. Their job is to raise hell about a system that has turned American society into a pyramid and made a mockery of American democracy and to build a social movement that practices radical, leaderless, direct democracy.

On September 29, the General Assembly issued a consensus statement on what the protests are against: they are against allowing corporate economic power to "run our governments," and they are against predatory banking and foreclosures, the bailing out of megabanks and the perpetuation of inequality and discrimination "based on age, the color of one's skin, sex, gender identity and sexual orientation."

The group also protested monopoly farming and the poisoning of the food supply, the abuse of animals, unsafe working conditions, the financing of education through student debt, outsourcing labor, the legal status of corporations as persons, lack of health coverage, the erosion of privacy and the abuse of military and police power. These protests were lodged against an unnamed "they": "They have poisoned the food supply through negligence . . ."

The crowds that have showed up in Zuccotti Park include people from every racial and ethnic community and all ages. There are tensions between insiders who sleep in the park and speak the movement's language and outsiders who show up occasionally or for the first time. Drop-ins sometimes wince at the odor and messiness of the occupation, and occupiers work hard at being hospitable. Hard words have been spoken between progressives who work in the left wing of the Democratic Party and radicals who think that trying to change the system from within is obviously pointless and corrupting. MSNBC anchor Ed Schultz got a mixed welcome at Zuccotti Park. Schultz wants the protesters and President Obama to help each other, but to many of the protesters, Obama is a bigger obstacle to the movement than a President Romney or President Perry would be, because loyalty to Obama restrains many progressives from breaking with the system.

Occupy Wall Street has set off something that is already too big not to make a difference. Coalitions are forming that were not possible two months ago. I believe that the organizers were right to concentrate on building a social movement and not issuing a list of demands. Any policy prescription would have been divisive and disabling in the early going. Sooner or later, however, this movement has to make demands and decide what it stands for constructively. I hope that it will opt for decentralized economic democracy and coalesce around some fundamental policy demands.

Whatever else the movement might pursue regarding Wall Street, two reforms belong at the top of the agenda: 1) preventing banks from becoming "too big to fail" and 2) strengthening the Volcker Rule, which aims to restrict banks from making speculative investments.

Today the seven largest banks hold assets equal to 66 percent of GDP—a staggering concentration of economic power in a democracy. Twenty years ago that figure was only 18 percent. The big banks, being too big to fail, got even bigger after they got their bailouts. During the 2010 Senate debate over the Dodd-Frank financial reform bill, Senators Sherrod Brown (D., Ohio) and Ted Kaufman (D., Del.) proposed sensible limits on the size of megabanks, with caps large enough to allow effective economies of scale. They argued that no single bank should be allowed to risk more than 3 percent of the nation's gross domestic product. A cap on bank size would put an end to the too-big-to-fail syndrome and free up lending to small businesses that megabanks spurn.

The Brown-Kaufman amendment imposed a 10 percent cap on any single bank or holding company's share of the U.S. total insured deposits. It limited the size of nondeposit liabilities to 2 percent of the nation's GDP for banks and 3 percent for nonbank institutions. And it established a 6 percent leverage limit for bank holding companies and select nonbank institutions.

This amendment, had it been included in the Dodd-Frank bill, would have broken up the nation's six largest banks. It won 30 Democratic votes and three Republican votes in the Senate, despite failing to win the support of the Obama administration or the Senate Democratic leadership. Brown-Kaufman would have passed had Obama supported it. But according to Obama, the Volcker Rule was a better way to restrain the speculative excesses of the big banks. It didn't help that Obama's Treasury secretary, Timothy Geithner, was the chief architect of making the megabanks bigger. As New York Fed chair during the financial crisis, Geithner cut the bailout deals and played matchmaker for bank mergers.

The Volcker Rule got into the Dodd-Frank bill only in mutilated form, and the big banks are trying to eviscerate what's left of it. The Volcker Rule, conceived by former Federal Reserve chair Paul Volcker, seeks to minimize conflicts of interest between banks and their clients by prohibiting banks from simultaneously entering into advisory and creditor roles with their clients. In essence, it attempts to reinstate the wall between commercial and investment banking established by the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933, which created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and excluded commercial banks from the securities business.

In 1999 the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act tore down the Glass-Steagall wall, allowing investment banks and commercial banks to merge. This invited speculative investment and opened the door to the megabank empires and mergers of the Bush years. Volcker, surveying the wreckage in 2009, implored that it was not too late to repeal Gramm-Leach-Bliley. In a world gone so awry, he contended, the seeming quaintness of this view was not a defect: "People say I'm old-fashioned and banks can no longer be separated from nonbank activity. That argument brought us to where we are today."

By October 2009, Obama agreed with Volcker, but Geithner and Larry Summers, head of the National Economic Council, were opposed. Geithner contended that prohibiting banks from speculating for themselves would unnecessarily hamper America's wealth machine. Summers worried that the Volcker Rule would prompt many banks to opt wholly for speculative trading. If the big banks had to choose between gambling for themselves and taking care of customers, they would choose themselves. And if they got out of banking, the system would be plunged into another crisis. Geithner and Summers, though respecting Volcker's iconic status, admonished Obama that the financial world had left Volcker behind.

But the Volcker Rule made sense to Obama, who argued that it had been a serious mistake to allow banks to stray from their mission of serving customers. The federal government provides deposit insurance and other safeguards to ensure that America has a stable banking system. These privileges were not created to give advantages to banks operating hedge funds or private equity funds. It is inappropriate, Obama maintained, for a bank to speculate with cheap money that the government safety net provides.

Worse yet, Gramm-Leach-Bliley allows banks to make trades that conflict with the interests of their customers. The system allows hedge funds and private equity firms inside banks to place risky bets, posing obvious risks of conflicted interest, which taxpayers subsidize. Obama rightly argued that the system is unacceptable on both counts, plus it fuels a riot of speculation. The best remedy for too-big-to-fail syndrome is to draw a line between trading for customers and trading for yourself.

This was not mere technocratic tinkering. This was using political power to change the system. In the spring of 2009, as the Dodd-Frank bill moved through the Senate, the Securities and Exchange Commission offered an instructive example of what was (and still is) at stake by filing a civil suit against Goldman Sachs for misleading investors in an opaque collateralized debt obligation (CDO) deal, or Abacus deal.

Goldman routinely shorted (betted against) CDOs that it created and marketed to investors—a showcase example of the unseemly but legal double dipping that Volcker wanted to prohibit. According to the SEC, however, Goldman took a further step in its Abacus 2007-AC1 deal by creating a derivative that was designed to fail at the request of a client, John Paulson, who wanted to bet against it. Paulson is the head of a giant New York hedge fund that made billions betting against the housing market. The SEC said that Goldman misled investors by not disclosing that Paulson handpicked some of the bonds underlying the derivative. Goldman said it had no obligation to do so.

This case proved enlightening to many who were just beginning to pay attention to what Wall Street has done to the country. The ostensible purpose of Wall Street is to raise money to finance making things in the real economy. But CDO deals are not investments. They do not create any actual bonds or mortgages or add anything of value to society. They are gambles on whether somebody else's bonds will succeed; they inflate the housing bubble without financing a single house. They are like side bets at a casino, except the Federal Reserve implicitly protects these bets. Moreover, according to the SEC, Goldman looted its own customers.

The Goldman case and a flock of media stories about Wall Street corruption incited public rage at a delicate moment, as Democratic senators competed to strengthen the financial reform bill. But in the end, the Dodd-Frank bill could not pass without the vote of Massachusetts Republican Senator Scott Brown, who gutted the Volcker provision, demanding exemptions for proprietary trading in Treasury bonds, bond issues by government-backed entities such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and municipal bonds. Advocates of the Volcker Rule lamented that these exemptions would surely breed others. Volcker agreed that what passed was not the Volcker Rule. Regulators are now debating how to implement the bill that was passed.

The Dodd-Frank bill contained some worthy reforms. It required most derivatives to be traded on a public exchange and cleared through a third party to guarantee payment if one of the trading parties goes out of business. It expanded the authority of the Federal Reserve, abolished the inept Office of Thrift Supervision and established a new Financial Services Oversight Council, chaired by the Treasury secretary. It established a new consumer agency and authorized regulators to require higher capital reserves. It won greater authority for shareholders over how much corporate executives should be paid and called for new rules on the trading that financial companies do with their own accounts (proprietary trading).

These were significant victories in the face of an overwhelmingly better-funded opposition. But the lobbyists and political opponents riddled the bill with poison pills and loopholes—carve-outs for select corporate users of derivatives, exemptions for foreign exchange swaps—and it restricted scrutiny of corporate pension funds. The plan's heavy reliance on the Federal Reserve is a mixed blessing at best, as the Fed is very friendly to the big banks and the new consumer protection agency is housed there. The bill did not require higher capital reserves or abolish gambling with CDOs. It took a pass on the biggest problem—that the ever-growing too-big-to-fail banks are too big to be regulated.

Wall Street is pouring over $50 million per quarter into gutting the Dodd-Frank rules; thus far it has won victories on debit card fee caps, oversight of complex derivatives and leadership of the consumer protection agency. In the first quarter of 2011 alone, Wall Street spent $52 million to weaken the Dodd-Frank Act.

I have focused on the too-big-to-fail syndrome and the Volcker Rule because these reforms could potentially make the biggest difference and because pressing for them is no more of a long shot than other important reforms, such as demanding that Wall Street invest in the job-creating real economy instead of gambling on credit default swaps, stopping the ruinous speculation on gasoline and heating oil, establishing a speculation fee on derivatives and futures (the U.S. had such a fee from 1914 to 1966) or capping credit card interest rates.

Simon Johnson, chief economist of the International Monetary Fund in 2007-2008, argues that the finance industry has effectively captured the U.S. government. At the IMF Johnson got a close look at the symbiotic relationships between the world's economic elites and its governments. In the U.S. the symbiosis goes far beyond mere access or even collusion, he says; here government and high finance are melded together. That is a problem when the oligarchy screws up and the economy implodes.

Johnson stresses that when the IMF enters the scene of an economic crash, the economic part is usually straightforward. Nations are told to live within their means by increasing exports, cutting imports and breaking up bankrupt enterprises and banks. Every country that is not the U.S. would get this prescription. But the U.S. controls the IMF, it has a powerful and well-connected oligarchy, and it pays its foreign debts in its own currency. So our recovery began by paying off Wall Street.

There are significant differences between the South Korean and Indonesian crashes of 1997, the Malaysian crash of 1998, Japan's lost decade, the recurrent crashes in Russia and Argentina and the U.S. meltdown of 2008. But they all have in common one important thing: a financial oligarchy that rigged the game in its favor, built an empire on debt, overreached in good times and brought the house down on everybody. When the house collapses, elites do what they always do: they take care of their own. To get a different result, a nation has to take control of the problem and break the grip of the oligarchy.

If the U.S. opts for muddling through the next decade, it can just print more money and ride out the deflationary spiral. That is the path we are on. Deflation, once started, has a terrible tendency to feed on itself. Income falls in a recession, which makes debt harder to bear, which discourages investment, which further depresses the economy, which leads to more deflation.

Today businesses are holding back because they lack customers, not because they lack confidence in the government's efficiency or competence. The economy is sluggish because of weak consumer demand caused by stagnant wages, job uncertainty and the ongoing ravages of the mortgage disaster, not because the low taxes that Americans pay are somehow too high.

Creating a healthy and productive workforce is far more important than the fluctuations in tax rates that political campaigns obsess over. Educating the workforce for 21st-century jobs and investing in research and technology are more important. Sustaining a middle class that buys goods and services is more important. Developing a strong infrastructure (the U.S. ranks 23rd in the world) and saving for investment (most Americans have no savings) are at least as important as tax rates.

The U.S. cannot move forward without making massive investments to build a clean energy economy. Labor costs, equipment costs and the cost of capital will never be lower than they are today. The U.S. has massively underinvested in infrastructure for decades, and a national infrastructure bank, once created, would plow money into infrastructure rebuilding on an ongoing basis. If we can spend trillions of taxpayer dollars bailing out banks and setting up "bad bank" contraptions to eat their toxic debt, we ought to be able to create good public banks at the state and federal levels to do good things.

Public banks could finance start-ups in green technology that are currently languishing and provide financing for cooperatives that traditional banks spurn. Cooperatives can be established at the state level, following the leads of North Dakota and Washington, to create state credit machines not dependent on Wall Street. They can be established at the federal level by congressional mandate or by claiming the good assets of banks seized by the government, or both.

If we democratize economic power and the process of investment—breaking the dominance of Wall Street, investing in full employment and a green economy, strengthening social market sectors that serve the needs of communities, and creating public banks and new forms of socially owned enterprises—we get something better than the regime of inequality and deflation that has been laid out and is leading to the evisceration of Medicare and Medicaid.

Occupy Wall Street will probably not produce theories of economic democracy or policies for it. But to their immense credit, the occupiers set off the first protest movement that responds with anything like the moral outrage that is appropriate to the situation.