The Dutch Bible Belt

I am writing these words in the heart of the Bible Belt. I'm in a small town that is traditionally pious but has swelled in recent years with the infusion of well-educated commuters who have left the nearby big city to escape crime and immorality. Here and in neighboring communities, newly built megachurches are growing. They preach a very traditional orthodox theology. Also booming are hardline right-wing political parties which take very conservative positions on issues such as homosexuality, abortion and gender roles.

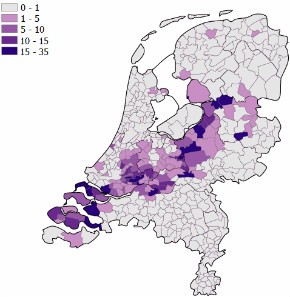

This certainly is not the standard picture that Americans have of the Netherlands. But the Dutch have a Bible Belt, or Bijbelgordel, which runs from the northeast of the country to the southwest. Its borders can be easily mapped using patterns of religious affiliation and political voting. It is not a large territory—in places it is only 30 or 40 miles wide—but it represents a substantial portion of this small country (the entire Netherlands is only about as large as Maryland and Delaware combined).

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The persistence of a rigorously orthodox Protestant area in such a bastion of progressive liberalism must make us rethink any generalizations we might be tempted to make about the state of religion in Europe as a whole.

The belt is the location of the conservative and ultraorthodox Reformed churches and sects that refused to join the general movement toward Protestant unity. Although these groups account for just 4 or 5 percent of the population, their geographical concentration gives them a profound influence. In the purest orthodox communities, women long wore the traditional clothing that defined these black-stocking churches. In this area at least, church leaders can still aspire to the kind of Calvinist moral discipline that prevailed in places like Scotland, the Netherlands or New England in 1630. Everywhere, the sabbath is strictly observed, and it's enforced by law in some communities. Many families refuse to own televisions. Some villages ban swearing.

The Netherlands was long famous for the "pillars" that defined everyday life. People adhered to one or another of three pillars, Catholic, Protestant or Socialist-secular, and that membership strictly determined the schools and institutions that one attended, the newspapers and radio programs that shaped one's opinions, and the political parties one voted for. The collapse of those pillars in the 1960s contributed powerfully to the general secularization. But among the ultraorthodox churches, the pillars survive intact, allowing believers to live their whole lives within denominational limits.

The new megachurches demonstrate this local power. Built by sects like the Gereformeerde Gemeenten (Reformed Parishes), megachurches have arisen in the past decade or so in belt towns like Barneveld, Veenendaal, Staphorst, Opheusden and Zwolle. The buildings seat 2,000 to 3,000 every Sunday, and like American megachurches they offer a comprehensive roster of activities throughout the week. One church in Drachten has been proudly termed the European Saddleback.

As in the United States, the Dutch Bible Belt has long been a base for conservative political activism. One potent movement is the long-established Reformed Political Party (Staatkundig Gereformeerde Partij, or SGP), which holds extraordinarily traditionalist views on gender and social issues. Not until 2006 did the party even admit women to full membership. It supports repealing most aspects of Dutch social liberalism and seeks to restore capital punishment in accordance with biblical teachings. Although the SGP has next to no presence in most of the nation, it regularly attracts 10 to 15 percent of votes in the Bible Belt, and it constitutes the majority in some small communities. Other conservatives favor the ChristianUnion, which in recent years has shocked some observers by taking its strongly pro-family and communitarian message outside the ultraorthodox heartland.

Of course, groups like the SGP can never dream of national political power. Bible Belt church leaders need never confront the compromises of religious principle that a national political effort would entail. Other political trends, though, raise real concerns, especially the rise of new national right-wing movements that threaten to seduce tradition-minded religious voters.

The greatest danger is the Party for Freedom, led by anti-immigration and anti-Islam activist Geert Wilders, who might someday win national power. While agreeing with Wilders's calls to assert and defend Christian civilization, Protestant pastors worry that their moral message might easily become lost in racist and anti-immigrant rhetoric. Although the Dutch Bible Belt has succeeded, almost incredibly, in keeping its identity through the centuries, real conflicts lie on the horizon.