Marketing plan: A mainline church in the Bible Belt

For ten years, I was the pastor of First United Methodist Church in Lebanon, Tennessee, a Bible Belt corner of the world that's chock-full of religious right, fundamentalist congregations. Every year on the anniversary date of Roe v. Wade, a church in that community places thousands of white crosses on its front yard. Every July 4, that same church puts out thousands of American flags. In a recent sermon, its pastor announced that "homosexuals will not be allowed into heaven." The vast majority of churches in my town are kindred spirits with that congregation.

I regularly received postcards from these conservative churches advertising their upcoming sermon series. About eight years ago I did some informal research and confirmed that the postcards are successful in attracting first-time visitors. Why, I asked myself, don't mainline churches advertise as successfully as these churches? That question led to an experiment. Our staff decided to create a compelling, mainline-appropriate worship series and market it to our community.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The title for the series came from a conversation I once had with Danny. When I first met Danny, he said, "Preacher, you need to know that I'm an atheist. I don't believe the Bible. I don't like organized religion. And I can't stand self-righteous, judgmental Christians."

In spite of Danny's avowed atheism and my devout Christian beliefs, we became close friends and shared many conversations about faith. One day Danny announced with a laugh, "I've decided to upgrade from being an atheist to being an agnostic." Several months later he said, "I've had an epiphany. I realize that I don't reject Christianity. Instead, I reject the way that intolerant Christians package Christianity." A few weeks after that conversation, Danny said, "Martin, you've just about convinced me on this religion stuff. So I want to know—what's the least I can believe and still be a Christian?"

That question became the title of the sermon series (and eventually of a book). Over a seven-week period, I preached about several things that Christians don't need to believe. In short, Christians don't need to believe in closed-minded faith. They don't need to believe that it's heresy to believe in evolution, that Jews are going to hell or that women can't be preachers. I then turned to what Christians do need to believe. They need to believe in Jesus—his life, teachings, example, death and resurrection. A great benefit of these beliefs is that they provide promising answers to life's most profound questions: What matters most? Where is God? What brings fulfillment? What about suffering? And is there hope?

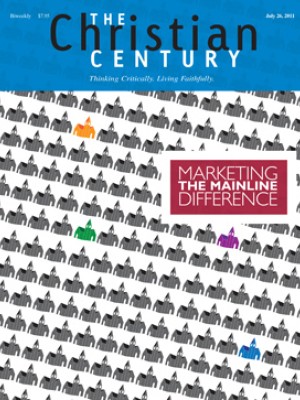

The series electrified our congregation, brought in a large number of guests and netted new members. We began to understand that we had a great opportunity to brand ourselves as a mainline church in a sea of fundamentalist churches. While we were not better than our sister churches, we were different, especially in our worship, our theology and our emphasis on grace. Most members were overwhelming enthusiastic about marketing this difference. Over the next few years we became bold in our identification with—and marketing of—our mainline connection.

The first thing we learned is that marketing ourselves as a mainline church came with a cost. The cost was not large but included both internal conflict and external criticism.

Internally, our initiative led one of our staff members to "come out of the closet" as a fundamentalist. Along with a few of his close friends in the congregation, he created a grand plan to change our congregation into a fundamentalist church. That plan included getting rid of me as pastor. He began to tell people that I was a "false prophet" and that I "did not believe the Bible."

Thankfully, his crusade failed. He resigned (instead of being terminated) and only a few people left the congregation. The experience took a toll on me and on other staff, but I had decided that maintaining our mainline identity was a "ditch I was willing to die in." Thankfully, that proved unnecessary. But a congregation that decides to boldly proclaim itself as a mainline church can expect some internal conflict.

We also paid for marketing our mainline identity with some external criticism. As you might expect in our community, other local clergy sometimes criticized our church. We found that the criticism had its benefits, however, as when a man at our local fitness club told me, "You don't know me, but I know your church. It's the one that's nonjudgmental, open-minded and inclusive." That kind of reputation is worth occasional put-downs from local fundamentalist pastors.

The second thing we learned about marketing mainline congregations is that, contrary to popular opinion, mainline laypeople are willing to engage in evangelism but won't use the word evangelism, which conjures up images of high-pressure, obnoxious gospel salesmen. Instead, they love the idea of being an "inviting and welcoming congregation." When they were asked to invite and welcome people to our worship series, they did so with gusto.

Most of our growth can be attributed to these invitations, especially during the special worship series mentioned earlier. Although Lebanon is a small town, the church added 1,100 new members over ten years and doubled attendance.

The third thing we learned is that mainline churches can market themselves with integrity. Many mainline congregations cringe at the concept of marketing themselves. But for us it was about sharing the good news of mainline faith with our community. Word of mouth was our best marketing tool, and our members did a good job of talking up our church around town. They constantly lifted up their core value of being an "inviting and welcoming congregation."

We also got a lot of mileage from sermon series. After we did the "What's the Least?" series, we did "Jesus on Life" (the Sermon on the Mount), "God Lessons from the Great Recession" (various texts) and "Dead Man Walking: How a Burned-out Prophet Came Back to Life" (1 Kings 19). Even if you are a lectionary preacher, you might want to consider doing a similar series once a year to help market your church.

We promoted these series with bulletin inserts, newsletter announcements and e-mail. We prepared e-mail advertisements about our upcoming worship series, sent them to members of the congregation and asked them to forward them to family and friends, along with a personal invitation to attend worship. They did so faithfully.

The church maintains a website that's unashamedly mainline and includes articles such as "The Answer to Bad Religion Is Not No Religion but Good Religion." Members have a well-organized and intentional system of following up on visitors and constantly brand themselves as people with "Open Hearts, Open Minds, and Open Doors." The United Methodist motto is everywhere in the church, including in bulletins, newsletters and on the sign, website and postcards mailed to newcomers in the community. One couple told me, "When we saw your sign, we decided to visit. When we discovered that the church inside lived up to the sign outside, we wanted to become members."

The fourth thing we learned is that marketing alone is not enough to grow a vibrant mainline church. Unless we delivered more than a sales pitch, we'd lose our visitors. So we supplemented our outreach efforts with three other core values—quality worship, small-group ministry and community service.

We practiced a blended worship style that we called "ancient-modern"—it incorporates historic, traditional and contemporary styles of praising our Creator. If you were to visit the church, you'd see frequent celebration of Holy Communion, affirmation of the Apostles' Creed and anointing of oil for healing and wholeness. In the early contemporary service, you'd find praise choruses, drums and guitars, and projection screens.

After attracting people to worship services, members work hard at connecting them to small groups. I once heard a story about a northerner who came down south for a business conference. On his first morning in town, he went to eat breakfast at a little mom-and-pop diner close to his hotel. He ordered eggs, sausage and toast, but when the waitress brought his order, he noticed a little pile of white stuff on his plate. "What's that?" he asked. "Grits," she said. "What is a grit?" he asked. "Honey," she drawled in her southern accent, "they don't come by themselves." Neither do Christians. The Christian faith is not an individual faith but a community faith.

We learned that the best way to experience Christian community is to participate in a small group. We offered Sunday school for all ages as well as music groups, Bible study groups, groups for men, women, youth and Scouts, and short-term groups like those on marriage enrichment and financial planning. Ten years ago 200 people were involved in weekly small groups; today more than 600 people participate. It is by far the most effective assimilation tool.

The church's final core value is community service. Several years ago we showed our congregation a tongue-in-cheek video called The Me Church. It features people making ridiculous demands of their church. One woman wants her car buffed and waxed during worship. A young man wants tickets to the Super Bowl. A little girl wants a pony. In every case the church meets the request. Then the video ends with these words: "The Me Church. Where it's all about YOU."

If we are not careful, we church leaders can spend all our energy meeting the needs of our own members while neglecting the rest of our community. But as Jesus inconveniently reminds us, church is not about us but about others. As a result, at First United Methodist, members are working to make community ministry a vital part of the culture. They established a counseling center and helped establish a homeless center for women and children. Every year they build a Habitat for Humanity house. They provide a food pantry and are about to launch a soup kitchen. They've become involved in earth-care concerns.

This fourfold combination of community service, quality worship, small-group ministry and aggressive marketing was the key to growth and vitality. Large numbers of people are starving for an alternative to closed-minded, judgmental, antigay, antiwomen, antiscience, religious right fundamentalism. The Lebanon congregation responded by offering open-minded, grace-filled, gender-equal, socially conscious, life-giving mainline faith. People are coming to hear more.