Sunday, December 12, 2010

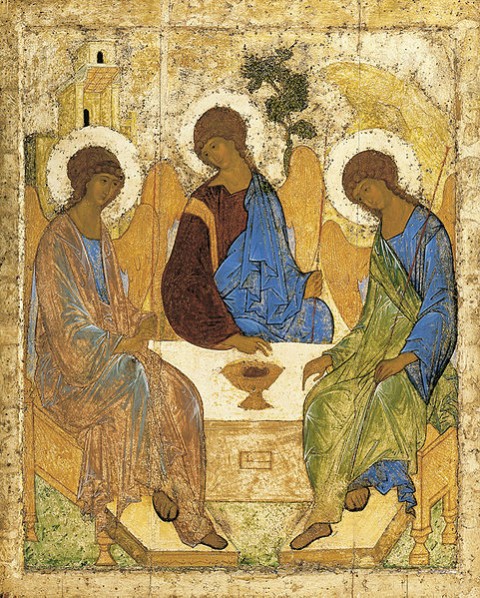

There is an ongoing debate about the angels in Andrei Rublev's icon of the Trinity, painted around 1410, and about which one represents the Son and which the Holy Spirit. For the Word become flesh, my money is on the one wearing blue and brown, for those hues suggest one who comes from heaven to earth to reconcile both in his one person.

In this Sunday's texts, brown abounds. Blessings flow "far as the curse is found." No topography is too remote (wilderness, dry land, desert, streams, sand, pool, swamp, earth), and no location is beyond Christ's reach (Lebanon, Carmel, Israel, highway, prison, palace). These Advent lessons "earth" our Christology in the soil of particular places.

Perhaps James isn't much interested in real farms, but only in the farmer as an analog for patient discipleship. Perhaps Matthew's specificity about John in prison is just good storytelling. Mary's Magnificat seems less interested in any place per se than in sending the rich away empty.