The Environmental Vision of Thomas Merton, by Monica Weis, SSJ

Thomas Merton was a monk, a poet, a contemplative, a peace activist, a nurturer of interreligious dialogue—and much more. Countless books have been written exploring most of these facets of Merton's life and work in the years since his tragic death in 1968. One aspect of Merton's work, however, is not so familiar: his commitment to ecological justice, especially during the final decade of his life. Monica Weis's delightful The Environmental Vision of Thomas Merton is a superb guide to the ecological themes of Merton's life and writings.

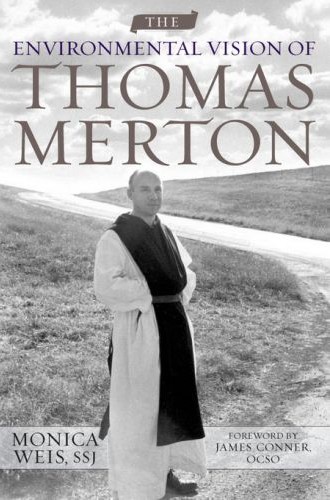

This book is the latest volume in the University Press of Kentucky's heralded Culture of the Land series. Weis, a sister of St. Joseph and a professor of English at Nazareth College in Rochester, New York, demonstrates that although environmental themes were most prominent in Merton's work in his last few years, a foundation was being built over the course of his lifetime, beginning during his early childhood, when his parents nurtured in him the art of attentiveness. Tracing his youth through a number of significant places Merton lived, Weis makes the case that his attention to the landscape of these places stoked in him a deep love for nature and wilderness. As he converted to Catholicism, followed a monastic call and then, toward the end of his life, increasingly adopted the life of a hermit, Merton became deeply focused on harmonizing his "inner geography" with the outer geography of his Kentucky landscape. Weis masterfully narrates this journey, focusing particularly on Merton's journals and poetry. Merton's own photographs, which illustrate the volume, demonstrate his deep love for nature and his keen attentiveness to the Kentucky landscape around the Abbey of Gethsemani.

A key point in the development of Merton's environmental vision was his reading of Silent Spring, Rachel Carson's 1962 critique of the widespread use of the chemical DDT as a pesticide. Merton was so moved by the book that he penned a letter of gratitude to Carson, calling Silent Spring "perhaps much more timely than even you or I realize," admitting the "follies" of his own previous use of DDT and stating that he had renounced the practice. Weis emphasizes that the writing of this letter represents a crucial point in Merton's life, a time of "significant enlargement of vision." Previously Merton had been deeply involved in issues of human justice, but after reading Silent Spring and writing to its author, he demonstrated a turn toward deeper concern about ecological justice and caring for the Earth.