So much Twain

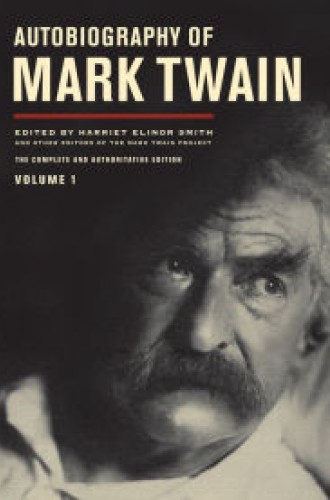

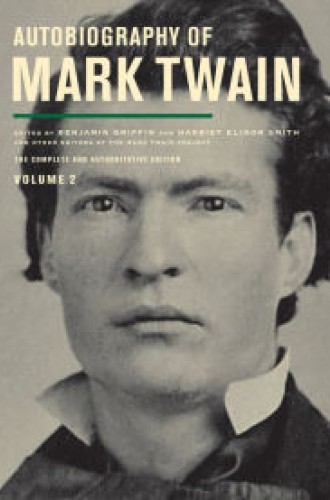

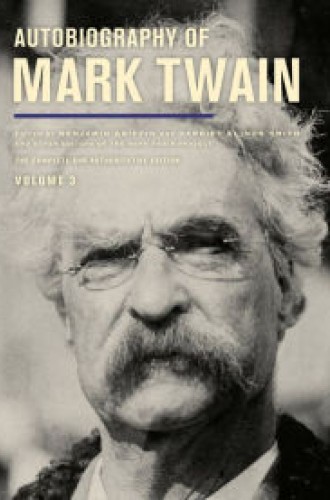

Together, the three volumes are five inches tall and weigh more than my children did when they emerged from the sea of their mother.

Many readers who know and love the works of the astonishing American polymath Samuel Clemens—better known as Mark Twain—are vaguely aware of the story of his autobiography. Between the ages of 35 and 69, Twain tried many times to write or dictate stories of his long and colorful life, each time getting a few reminiscences or a chapter down before moving on impatiently to other projects. This was a man who wrote some 30 books, was a licensed riverboat pilot, was briefly and ineptly a Confederate volunteer, was a (terrible) silver prospector, hobnobbed with the greatest writers and social figures of his time, traveled around the world, patented three inventions, was happily married and blessed with daughters—and much more.

However, as 1906 began, he hit upon a system that finally produced a vast manuscript of more than half a million words: he hired a brilliant stenographer, Josephine Hobby, and he abandoned all thought of chronology, preferring simply to tell a tale, which reminded him of a story, which reminded him of a person, which reminded him of an adventure, which reminded him of a funny anecdote, all of which the talented Hobby would capture in full flow, complete with the pace and rhythm of Mark Twain the glorious and legendary raconteur.

Thus the ur-Autobiography, which Twain insisted could not be published until a century after his death, because in the dictation he had been wholly free with “every private opinion I possessed relating to religion, politics, and men”—many of these bitter, insulting, and sure to bring public fury had they been published in his lifetime.