Sacrament of friendship

I finished this epistolary memoir the same day that the conclave of cardinals chose the new pope. Watching that white smoke billow from the chimney of the Vatican, I and millions of other viewers were moved by this mysterious, ancient form of communication. That lovely smoke both disclosed information and obscured it: it told us that there was a new pope and reminded us how little we knew.

Although writing letters is not as antiquated as sending smoke signals, reading letters between other people can feel a little like watching the Vatican chimney. Even as we learn about the correspondents, we are reminded that we stand outside a conclave of two. The reader becomes a silent correspondent of sorts, conversing with the authors as she reads but remaining ever on the outside looking in.

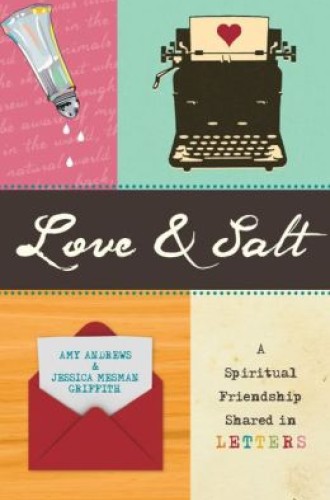

Love and Salt is full of sacramental imagination. Amy Andrews and Jessica Mesman Griffith render things like a walk through a graveyard, a dream about an elevator, and a Neil Young song into something else entirely.