Rev.

I turned to Rev. belatedly, having ignored friends’ praise and a British TV audience nearing 2 million. I feared it would reprise the mid-1990s sitcom The Vicar of Dibley, which portrayed with saccharine sweetness a woman vicar in a rural parish. Episode one of Rev. (available at Hulu.com) set me straight.

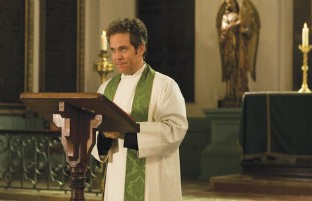

The Rev. is one Adam Smallbone (played by the wonderfully blinky Tom Hollander), a pastor who responds to lewd gestures from construction workers by carefully taking off his collar, fixing his gaze on the workers and shouting, “Why don’t you just fuck off?” This is a pastoral portrait drawn in a post-Christendom world: we see a tow truck drag away a hearse that is parked directly in front of the church—and this happens during a funeral.

The makers of Rev. seem to get church life. St. Savior in the Marshes is a struggling city parish willing to try new things, but members get nervous when evangelicals from elsewhere in the diocese pull out pews, hire a DJ, install a smoothie bar and impugn women’s ordination: