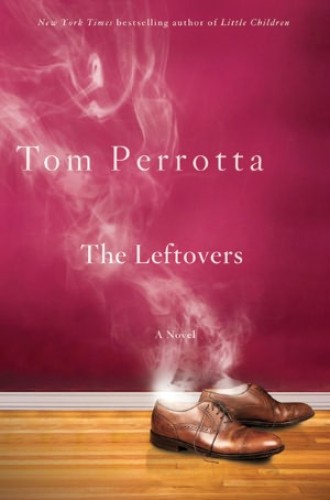

The Leftovers, by Tom Perrotta

What if the Rapture really happened? This is the question Tom Perrotta takes up in his novel The Leftovers.

The novel opens with a retrospective description of the “Sudden Departure,” which happened a year or so before the prologue. One day, millions of people were just gone—poof. Residents of Mapleton, the Everytown, USA, suburb where the book takes place, disagree about whether the event was the biblical Rapture or something else. The Christians can’t help but notice “the diversity of the disappeared. Muslims and Buddhists were gone alongside Christians; gays, lesbians, and adulterers joined the ranks of what seemed unlikely to them to be a heavenly throng.”

If the Rapture were to occur in a fashion similar to what premillennial dispensationalists anticipate, my theology would be rocked by God intervening in the world in such an unquestionably supernatural way. My sense of self, justice and holiness would be shattered if certain outspoken fundamentalists left me behind.