Russian heart

The opening lines of Dostoevsky's Notes from the Underground (1864) can hardly be described as inviting: "I am a sick man. . . . I am a spiteful man. I am an unattractive man. I believe my liver is diseased." Yet generations of readers have been engaged by the writer's exquisite self-awareness, his extreme ambivalences and his complex understanding of life in a dysfunctional society. The book is a touchstone in literary history, social theory, existentialism and theories of neurosis. In a prefatory footnote, Dostoevsky made the bold claim that, though his narrator is imaginary, "it is clear that such persons as the writer of these notes not only may, but positively must, exist in our society, when we consider the circumstances in the midst of which our society is formed."

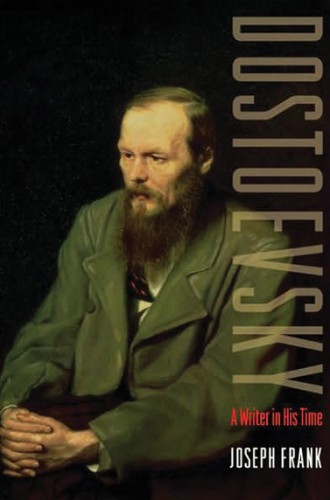

From his earliest works to his consummate achievement, The Brothers Karamazov (1881), Dostoevsky set a new standard for psychological verisimilitude that, as Joseph Frank points out, inspired many writers, perhaps most notably James Joyce, to experiment with ways of getting at truths we often hide, even from ourselves, and at the root causes of psychological and social disorders. Freud considered him the greatest of all novelists.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

This one-volume edition of the remarkable five-volume biography Frank completed in 2002 reviews Dostoevsky's psychological, political and spiritual life. Frank points out that most biographers have focused on Dostoevsky's eventful personal life—especially his unjust imprisonment and near-execution in Siberia—and neglected to take sufficient account of the political and intellectual currents that shaped his work. "Indeed, one way of defining Dostoevsky's originality is to see in it [his] ability to integrate the personal with the major social-political and cultural issues of his day."

The extraordinary self-awareness evident in characters like the narrator of Notes from the Underground and the astute diagnostic sensibilities of the narrators in The Possessed and The Brothers Karamazov mirror Dostoevsky's own capacities. He was shaped by ambivalences about family (his revered father was a violent alcoholic); Russia (his sympathies were divided between Europeanizing "Westernizers" and patriotic "Slavophiles"); and himself. At 26 he wrote to his brother and confidant Mikhail: "I have such an awful, repulsive character. . . . I am ready to give my life for you and yours, but sometimes, when my heart is full of love, you can't get a kind word out of me. My nerves don't obey me at such moments."

As with many 19th-century writers, references to "nerves" covered a broad range of psycho-physical tendencies, from mood swings to uncontrollable compulsions to—in his case—epileptic fits, which started at age nine and plagued him throughout his life. Numerous biographers and critics have commented on the relationship between Dostoevsky's epilepsy and that of characters like Prince Myshkin in The Idiot or Smerdyakov in The Brothers Karamazov. Frank goes well beyond tracing those connections to consider Dostoevsky's own concern over what he called his "mental illness."

"I always suffer from the unjust conclusions drawn about me," Dostoevsky told his brother. He was mocked, avoided, rejected and rebuked for his aberrant behavior by the writers and critics he counted on for acceptance—including Ivan Turgenev, with whom he had once enjoyed an exhilarating friendship. At such times he vacillated between defending himself and retreating into elaborate repentance and self-castigation. The latter response was especially true during his cycles of compulsive gambling.

His second wife, Anna, bore the brunt of repeated gambling sprees that left them nearly penniless. In addition to enduring those losses, she bore his frantic, self-abasing pleas for forgiveness. That she did forgive him, time after time, and remain faithful to him through poverty, public controversy and the deaths of two of their four children may offer some insight into his capacity for creating heroic, long-suffering women characters.

Frank's account of the Dostoevskys' much-tested marriage is deftly embedded in an account of the economics of publishing and the fortunes of the periodicals that published his stories. Those fortunes in turn depended on ideological fashions among the reading audience. Dostoevsky's work primarily appealed to intellectuals (though he drew heavily on Russian folk tradition and customs), people who argued passionately and publicly over the plausibility of Christian faith in the post-Enlightenment world, the validity of fantasy and imagination, the appropriate uses and aims of art, and the relationship of art to the institutions of church and state.

Dostoevsky's own concerns ranged from the relationship between sin and suffering to the ubiquity of money in human conflict. Speaking to us across a considerable historical and cultural divide, his novels continue to involve us in essential questions of theology, social justice and moral responsibility—about what it means to live in unjust servitude, about how to be our brother's keeper, about how even acts of violence may call for compassion, about how personal decisions intersect with politics and public life, and about how to retain an authentic faith in a world and church in which God is dismissed, oversimplified or institutionalized.

The section and chapter titles give some measure of how many angles of vision are represented in Frank's portraiture. "A Russian Heart" offers a sympathetic view of Dostoevsky's passionate feeling for a culture he couldn't bear to see neutralized or eviscerated by Westernizers. "The Insulted and Injured," a reference to one of Dostoevsky's own early titles, provides a glimpse of the writer's chronic sense of marginalization. "History and Myth in Demons" articulates the dialogue of fact and imagination that create the tense counterpoint in that novel and in Dostoevsky's own understanding of the role of the fiction writer as historian. "Rebellion and the Grand Inquisitor" comments on Ivan Karamazov's dark vision, in The Brothers Karamazov, of Christ and on the paradoxes of Dostoevsky's own complex faith.

Dostoevsky was convinced that "to love man like oneself, according to the commandment of Christ, is impossible. The law of personality on earth binds. The ego stands in the way." In response to that sorrowful claim, Frank comments: "It is only in the afterlife that 'the law of personality' could be decisively overcome."

Frank gave himself unstintingly to the task of biography, taking the time to master Russian, delve into archives and reflect on others' scholarship. Yet for all his thoroughness, he is never pedantic. Like Dostoevsky himself, Frank urges us toward a wide and generous view of character, a critical comprehension of political and social pressures, and a deeper understanding of how personal pain may be transformed in creative work. Like his subject, he invites us to take due account of "the circumstances in the midst of which our society is formed" and to refrain from easy judgments. He writes with a compassion that can only come of having entered into the great and troubled mind of his subject and identified in some measure with the spiritual longings of Dostoevsky's most memorable characters.

Frank understands Dostoevsky in terms of what he calls the writer's "eschatological imagination," preoccupied with ultimate consequences of ideas and beliefs. As a longtime professor of comparative literature, Frank also positions Dostoevsky in relation to great writers such as Sophocles, Dante, Milton and Shakespeare. Frank's five-volume biography has been called "magisterial" and "monumental," as well as "nuanced," "lucid" and "penetrating." The same might be said of this shorter version.