Trouble the Water

Tia Lessin and Carl Deal’s documentary Trouble the Water is a devastatingly effective depiction of the experience and aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. It isn’t the first: Spike Lee’s exhaustive, four-hour When the Levees Broke ran on HBO in 2006. But superb as most of Lee’s movie is, with footage that sticks in your head for months afterward, it starts to repeat itself and devolves into a rant against the ineptitude and negligence of the federal government.

Trouble the Water comes in at a brisk 90 minutes, and though President Bush, New Orleans mayor Ray Nagin and FEMA director Mike Brown make brief appearances, Lessin and Deal don’t linger with them. The inadequacies of the powers that be are conveyed through the visual evidence and the exasperation of the handful of survivors the movie focuses on.

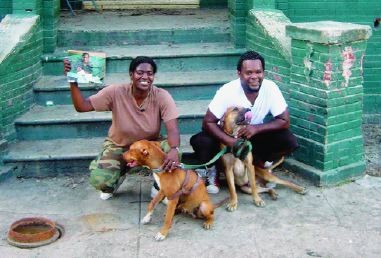

Among those survivors are Scott and Kimberly Roberts, a young couple from the Lower Ninth Ward who remained in the city during the hurricane because, like many others, they lacked the means to get out. Kim, an aspiring rap artist whose professional name is Black Kold Madina, used a video recorder to make a record of the ordeal, and Lessin and Deal build the film around her remarkable footage. (Black Kold Madina also provides the soundtrack music.)

Kim and Scott finally get out of their besieged house, negotiating the floods in a tiny boat, rescuing many others and eventually leaving the city in a truck they’ve managed to hunt down. They pass hundreds of desolate faces enduring the heat and waiting for the promised federal assistance.

Kim’s footage doesn’t contain the whole story; we hear some of it from them after the fact—like the story of how Kim, Scott and hundreds who sought shelter at a navy base were chased away at rifle point. Kim is as faithful as possible to her self-appointed mission to report her and Scott’s travails. We see them with a newfound friend in Alexandria, Louisiana, where her uncle has a house; back in New Orleans, surveying the damage (she discovers the body of a young drunk, a neighborhood figure whom she had warned to go inside before the storm struck); in Memphis, where they try to start a new life with the help of some cousins.

Lessin and Deal couldn’t have chosen a more compelling pair to follow. Kim has a complicated past. Her mother, a drug addict, died of AIDS when Kim was 13; her brother is in prison; and she has had her own skirmishes with the law. So has Scott. But they’ve been working hard to remake themselves, and Katrina enables them to do so. They become not just survivors but heroes. The testimony of one of the people they save from the hurricane, a wonderful, lanky old woman known as Miss Daisy who might have stepped out of a Eudora Welty story, is so effusive that Kim, who normally isn’t modest, hides her blushing smiles from the camera. Raucous and indomitable, Kim is a kind of earth spirit. Later we see her consoling Brian Nobles, who has been denied federal aid because he lived in a church-run home for recovering addicts before the hurricane struck and can’t come up with proof of residence.

Kim is determined to record her music, and Scott is equally resolute; when we see him for the last time, he’s working for a carpenter (they’re back in New Orleans, having been unable to earn a living in Memphis), cheerful and grateful, fixing up houses in his eviscerated hometown. The film doesn’t sentimentalize these two; it presents them with clear-eyed admiration and respect.

At the end of the film a perky representative from the New Orleans Bureau of Tourism declares that the city is back up and running, its tourist attractions having fortunately survived Katrina. She plays a video recorded before the hurricane that pays generic tribute to the city’s jazz heritage. Then a series of titles on-screen recites the sober facts of life for the city’s underprivileged. Kim’s rap song “Amazing,” which proclaims her refusal to become a casualty of her environment and her past, strikes a piercing contrast to the canned jazz on the video. It’s a living sound, made by an authentic citizen of New Orleans.