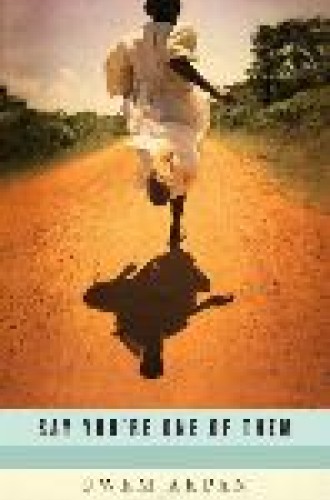

Say You're One of Them

The three short stories and two novellas that form this debut collection from Nigerian writer Uwem Akpan offer a stunning array of opening sentences:

“Now that my eldest sister, Maisha, was twelve, none of us knew how to relate to her anymore.”

“Best Friend said she liked your little eyes and lean face and walk and the way you spoke your English.”

“It was late afternoon. It was before the new democratic government placed a ban on mass transportation of corpses from one end of the country to the other.”

“I’m nine years and seven months old. I’m at home playing peekaboo in my room with my little brother Jean. It’s Saturday evening, and the sun has fallen behind the hills. There’s silence outside our bungalow, but from time to time the evening wind carries a shout to us. Our parents have kept us indoors since yesterday.”

And this devastatingly deadpan statement: “Selling your child or nephew could be more difficult than selling other kids”—the first sentence in “Fattening for Gabon.” It forecasts not just the plot—a tale of child trafficking—but also the skill with which Akpan, a Jesuit priest educated in Africa and the U.S. who teaches in Zimbabwe, writes about the most difficult and heart-wrenching topics.

There is little sentiment here and no sentimentality. Akpan thrusts us intimately into situations that we might prefer to keep at a safe distance on the nightly news. Maisha, the 12-year-old to whom no one can relate, is moving from part-time to full-time prostitution in an effort to provide for her family, who live on the streets outside Nairobi. Best Friend is a six-year-old Ethiopian Muslim girl wrenched from her Christian playmate when political unrest pits neighbor against neighbor. The mass transportation of corpses is instituted following an outbreak of mob violence between Muslims and Christians in northern Nigeria. The shouts that nine-year-old Monique and her little brother Jean hear are harbingers of the Rwandan genocide. And ten-year-old Kotchikpa is being fattened, along with his five-year-old sister Yewa, for sale to traders they are forced to call Mama and Papa.

But Akpan is no sensationalist. As shocking as these stories are, he does not mine them for their horror or use them as political propaganda. Akpan himself has said in an interview that “fiction allows us to sit for a while with people we would rather not meet,” and these stories invite us to linger with Maisha and Monique and Kotchikpa and Yewa. Indeed, they compel us to sit down, to come face to face with these child protagonists instead of looming over them with our adult sensibilities.

Children are drawn to possess things, to mark their place in the world with objects they can touch and hold. For eight-year-old Jigana, in “An Ex-mas Feast,” the talisman is a new school uniform tucked away in a carton at the very center of the family’s cardboard shack. The uniform, and the promise of attending a real school, symbolize the better life he can still imagine, despite growing signs of his family’s disintegration. For Monique and Jean, the talisman is a glow-in-the-dark crucifix hanging above the family altar in the parlor of their home. For Kotchikpa and Yewa, it is a Nanfang motorcycle imported from Holland that symbolizes freedom and access to a world outside their grinding poverty. Akpan uses these talismans to help us look not just at but with these children as they awaken to large and sinister realities. When Jigana realizes that Maisha will not be coming home again, he destroys his school supplies and turns his back on the new school uniform. The translucent crucifix is snatched off the wall and broken; the motorcycle fails to bear the children away to safety.

Although readers sense the deepening tragedies before the children in the stories do, Akpan keeps us focused on their perceptions. “My Parents’ Bedroom,” a finalist for the Caine Prize for African Writing, is told in the first-person present, so that along with Monique we only slowly recognize the extent and savagery of the unfolding genocide. We stay just one step ahead of the narrator and so are drawn into her soul. By contrast, the first sentence of “Fattening for Gabon” alerts us to the end of the story. As each new treat is offered to Kotchikpa and Yewa—the motorcycle, better food, fresh books for school, new godparents—we know it to be poisoned fruit, but we also taste its savory delightfulness. And as they are hardened into the privations of slavery, we drink the salt water with their tears and slowly suffocate in their prison storeroom. Small, emblematic scenes—Yewa carrying broken clay figurines “close to her heart, in open palms, like shattered pieces of a jewel”—foreshadow the heartbreaking trajectory of the plot.

Akpan’s child narrators are smart, sensitive, loving and determined. In the midst of horrifying situations, they are emotionally resilient and loyal to a fault. It is a tribute to Akpan’s craft that as we come to know the narrators, we feel hope rather than merely pity, despite the fact that no Mr. Brownlow comes to rescue these African Olivers. It is not merely the goodness of these children that makes them subjects rather than objects, but also the love they inspire in and share with their families. Monique’s Hutu father and Tutsi mother adore each other and their two small children, which deepens both the terror around them and the sacrifices they make. Kotchikpa’s AIDS-ravaged parents entrust their youngest son and daughter to an uncle who promises them a better life.

More surprisingly, even weak and despicable adults are revealed to be complicated characters. Jigana’s Baba, a small-time thief deeply in debt, sleeps the day away, sniffs glue and giggles futilely while his children slip away into prostitution and despair. And yet when he ties down Maisha’s trunk in a vain attempt to keep his family together or demands that his son pursue a better life, we sense a tug of empathy, a moment of recognition. (“No matter how bad somebody is,” Akpan has said, “I always try to put something into that character that complexifies it a bit for the reader.”) Even Fofo Kpee, the uncle who discovers that “selling your child or nephew could be more difficult than selling other kids,” shifts from monstrous to miserable, and the thought crosses our minds, Who are we to cast the first stone? even as we react viscerally to the brutality and sheer evil of child slavery.

The evil in these stories erupts from many directions—greed, failed economic policies, religious intolerance, corruption, tribal divisions, poverty, despair—and Akpan holds it before our faces unflinchingly. As we sit for a while with these children we consider the unraveling of the moral fabric of Africa. And it is fair to ask, Where is God in the midst of these horrors? The broken crucifix, the Christmas feast that marks the end of a family, the church that fails to intervene in the slave trade, the violence of Christian against Muslim, Muslim against Christian—all these seem more potent than the faith of small children, especially when that faith is betrayed or trampled.

And yet there are whispers of grace and faithfulness. A Muslim family hides Christians at the cost of their own lives; two little girls preserve their friendship despite deep religious divisions; the broken body of Christ casts its shadow across a broken and suffering Africa. If there is religious violence and religious apathy, there is also martyrdom and sacrifice. Love of God and love of neighbor intertwine, even when they exact a fierce cost.

We may be looking in the wrong place if we search for God only within the plots and among the characters of these stories. Akpan has said that he writes about African children in part because “the situation in Africa is very urgent and we need more people to help us see the complexity of our lives.” Similarly, in “Moral Fiction,” published in the Atlantic Monthly in 2005, Mary Gordon writes:

The moral good of fiction stems mainly from a habit of mind it inculcates in the reader. . . . What we might like to call the truth is often made up of several truths, including the first thing we thought, its opposite, and something in between. Some things cannot be known without careful pondering; horror can sometimes be averted only if we take our time to look and think and look and think and look and think again.

The responsibility of the writer is to write stories so compelling that we will take the time to sit with those we would rather not meet. The responsibility of the reader is to sink into these stories—to look and think and look and think again. As we do so, we may find ourselves sadder and wiser and drawn more deeply into penitence and true love of God and neighbor.