Nanking

Viewing Bill Guttentag and Dan Sturman’s Nanking is emotionally devastating. The film is a record of the Japanese occupation of Nanking in 1937, which entailed unimaginable cruelty. In addition to the wholesale slaughter of the Chinese, the Japanese committed 20,000 acts of rape in the first month of occupation, according to the Tokyo Tribunal on War Crimes, convened after World War II. The occupation also evoked extraordinary courage.

The courage was embodied in a handful of Westerners, mostly Americans, who refused to leave the city even after the U.S. embassy had ordered them to go home. Instead the Westerners struggled to create a safety zone for the Chinese, negotiating continuously on their behalf with the Japanese military, who raided the zone for men, whom they immediately sent off to their deaths as soldiers, and for women.

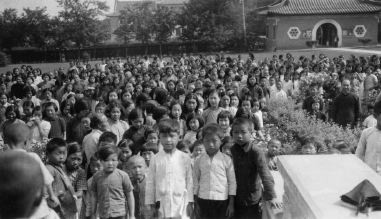

The Westerners were a disparate band of heroes: Minnie Vautrin, the dean of Ginling Girls’ College (which occupied the center of the zone); Lewis Smythe, a sociology professor at the University of Nanking; George Fitch and his fellow missionaries; an émigré German businessman named John Rabe, a devout Nazi (who believed Hitler would step in and rescue the besieged Chinese); and a surgeon, Bob Wilson, who wrote his wife back in the States that to return home “would be passing up the opportunity for service of the highest kind.” Together they saved 250,000 Chinese lives.

Guttentag and Sturman intercut newsreel footage, interviews with Chinese survivors (most of whom were children during the Japanese occupation) and Japanese soldiers, and first-person accounts, rendered by actors, based on letters and diaries of the dead. All the performances are fine; the best ones—Mariel Hemingway as Vautrin, Stephen Dorff as Smythe, Woody Harrelson as Wilson and especially Jürgen Prochnow as Rabe—are small marvels of emotional commitment and restraint. Prochnow renders Rabe’s fervency and compassion with surprising delicacy, while his eyes look wounded by what they’ve seen. The straightforwardness and lack of vanity in the acting is purifying: we never feel that the actors are standing between us and the historical events even as they guide us through material that is too brutal to bear.

The testimony of the Japanese soldiers is distanced, unemotional; you can hardly believe that the interviewers could get men who had participated in such atrocities to recount them in such detail. The Chinese interviewees are clear-eyed and articulate as they report on what they lived through. A woman remembers allowing herself, at 17, to be raped by soldiers over her grandfather’s protests because she knew that his intervention would simply get him killed. A man recalls the slaughter of an infant sibling. One man’s memory of seeing his dying mother struggle to suckle his wounded baby brother is as scalding a vision of hell as any offered in a film about war, whether a documentary or a drama.

The way Nanking successfully straddles the line between documentary and drama makes it one of a kind. The other element that keeps the movie pure is its refusal to soften the material by giving it a tone of moral uplift. A filmmaker might be tempted to let the heroism of the Westerners displace the unspeakable tragedy of the massacre. But to do that would be to break faith with those heroes and their sense that they hadn’t done enough.

Rabe returned to Germany to find that the Third Reich ignored his pleas and regarded him with suspicion. Vautrin, whose maternal instinct to protect her girls extended easily to the Chinese she managed to keep in the safety zone, returned to the Midwest and killed herself a year later. Rabe, at least, lived to see the mayor of Nanking travel to Germany after the war with money to ease Rabe’s declining years—money donated by those who felt indebted to him.

Nanking gets its tone from Vautrin and her cohorts’ ceaseless sorrow. It’s a work of art that seems to have been made out of tears.