Call of the wild

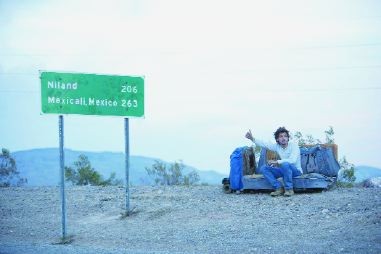

Fashioned from a book by Jon Krakauer, Sean Penn’s Into the Wild is an elegiac film about Christopher Johnson McCandless, who, upon graduating from Emory University in 1990, set out, without notifying his family, to live as elementally as possible in a manner inspired by Thoreau, Tolstoy and Jack London. He donated his life savings to charity, junked his car, burned his cash and traveled through the West and the Northwest (and, for a brief time, Mexico), taking odd jobs when he needed to and dreaming of Alaska. And that’s where he ended, holed up in an abandoned bus and starving.

Penn’s screenplay is set up as a series of flashbacks with a double frame: Chris’s final days and the voice-over narration by his sister Carine (Jena Malone). She provides background on the family and comments philosophically on her brother’s choices—which sadden her, but which she also champions.

Penn’s previous work as a director (The Indian Runner, The Crossing Guard, The Pledge) showed self-conscious poeticizing and a tendency to overindulge actors. Into the Wild is free-flowing but not undisciplined, the filmmaking is often truly poetic, and Penn’s work with his cast is consistently fine.

To carry the film he chose Emile Hirsch, the actor who made a strong impression in The Dangerous Lives of Altar Boys. Hirsch has an unusual quality that’s just right for Chris: a lyrical contemplativeness. He’s inward in a way that draws us in, and his physicality is plain but a little awkward. This tension underscores poignantly, and then tragically, the character’s essential haplessness. You admire Chris’s nerve but also recognize, when he lands in Alaska, that the odds are against his survival.

The most movingly explored theme in the film is that of family. As Carine’s voice-over makes clear, Chris’s conviction that he can live without human connection is provoked by bitterness about his parents’ embattled relationship and their materialism. Ironically, he continually runs into grownups who offer him the kind of selfless love he’s always wanted—people like Jan (Catherine Keener), a hippie who doesn’t know where her own son is, and Ron Franz (Hal Holbrook), a retired career soldier who lost his son and his wife in a car accident years ago. It takes Chris a while to realize that his efforts to pull away from other people have been misguided.

Keener and Holbrook, the latter’s familiar face wizened by age, give beautifully calibrated performances. Brian Dierker (as Jan’s partner) and Vince Vaughn (as Chris’s boss at a South Dakota grain elevator) also etch memorable characters. The only scenes that don’t work at all involve Chris’s parents, played by William Hurt and Marcia Gay Harden. Hurt’s silent expression of his grief over losing his son is the single example of the flamboyant emotionalizing that blights Penn’s earlier work. (The fancifully overwritten voice-over is the movie’s other flaw.)

A number of episodes are memorable, including some glancing ones, like that of Chris considering calling home and opting instead to give his last quarter to a man in the next booth who’s been cut off in the middle of begging his wife to forgive him. The film’s cinematographer, Eric Gautier, emphasizes the immense range of the land that Chris covers. And Eddie Vedder’s tremulous, craggy voice and the bardic style of the songs he’s written for the soundtrack offer the perfect complement to both Hirsch’s performance and the siren call of the wild that captivates Chris. In the final scenes, Chris looks like that voice sounds: his hair wild, his eyes deep-set and haunted, with an almost Inuit cast to his face. He’s already a ghost, and as you get up to leave you expect him to turn up in your dreams.