Wizard comes of age

In the third Harry Potter movie based on J. K. Rowling’s wondrous series of children’s novels, filmmaker Alfonso Cuarón takes the wheel from Chris Columbus, who steered both of the earlier pictures. It would be hard to think of a director with finer credentials for the job. In A Little Princess, he brought a witty, complex understanding of the ways children instinctually subvert adult authority. His scandalously overlooked Great Expectations, updated and set in the Gulf Coast and Manhattan, preserved Dickens’s spirit, and its saturated, expressionistic images hinted at what a young Bernardo Bertolucci might have brought to a contemporary American setting. Returning to his native Mexico with Y Tu Mamá También, Cuarón articulated both the hedonism and the private terrors of a pair of adolescents on an erotic adventure that drops them without warning on the thorny path to manhood.

Cuarón combines all these resources in Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. Working with screenwriter Steve Kloves (who penned both the first two Potter movies), he gets at the heart of the Rowling books, which chart the gradual—and rough—coming of age of the orphaned wizard Harry, who alternates between summers spent in the miserable suburban home of resentful relatives to school years spent at Hogwarts, a private school for the supernaturally gifted.

As Harry, Daniel Radcliffe was a bit of a stiff in the earlier films. Cuarón had him watch François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows and Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thief to prep for this one. That shorthand tutorial in the loss of innocence and the director’s own wizard’s touch with youthful performers have yielded fruit. The kid has turned into an actor. (So has Rupert Grint, who plays his eruptive carrot-top pal Ron Weasley; Emma Watson, as the prodigy Hermione, the third of the trio, was already there.)

In Prisoner of Azkaban, based on the most accomplished of the Potter books thus far, Harry has reached the age of 13. His discovery of the depth of his own powers implies a severing of his reliance on his father, who is no longer there to shelter him. That revelation is both painful and liberating. But he gains a new protector, his godfather Sirius Black (Gary Oldman). It’s Black, the wrongly convicted prisoner of Azkaban, the dreaded dungeon of the magic world, whose reckless escape sets the terms of the story.

The film begins with Harry’s own escape from his aunt and uncle (Fiona Shaw and Richard Griffiths), hilarious caricatures of narrow-mindedness and mean-mouthed tyranny. The opening sequence, where he takes illicit magic revenge for the insults of his uncle’s visiting sister by turning her into a balloon, sets free an anarchic comic spirit not found in either of the earlier pictures. Cuarón really gets into the unhinged mind-set of English farce.

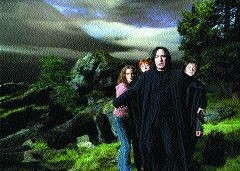

He certainly has the cast to pull it off. The combination of familiar faces—Robbie Coltrane as the part-giant Hagrid, whose compassion for the wildest of beasts figures large in this story; Alan Rickman as the permanently affronted Professor Snape (who looks like a pre-Raphaelite Hamlet); and the still-underused Maggie Smith as the Scots witch McGonagall—and new arrivals reminds us of the enduring glories of the British theater. Michael Gambon wears gracefully the cape of Hogwarts headmaster, Dumbledore, bequeathed by the late Richard Harris, and there are contributions from Emma Thompson, Timothy Spall, Julie Christie and David Thewlis.

To describe the visual sorcery in Prisoner of Azkaban would be to diminish the pleasures of discovery. Suffice it to say that, like the Lord of the Rings series, it’s a resplendent demonstration of the intersection of imagination and technology, and that it contains a trio of creatures—a woebegone werewolf, a black dog that seems to be made of mist, and something called a hippogriff—that suggest the dreams of true cinematic poets.

Cuarón draws on a pendulum motif to link the narrative strategy of the last act, which involves time travel, with the thematic idea of Harry’s (and his friends’) ascent into teenhood. It’s a marvelous idea, and typical of the way this director links storytelling, imagery, character and emotion.