Christian life in The School of Athens

My upbringing made me a Platonist. Motherhood made me an Aristotelian. I never left either behind.

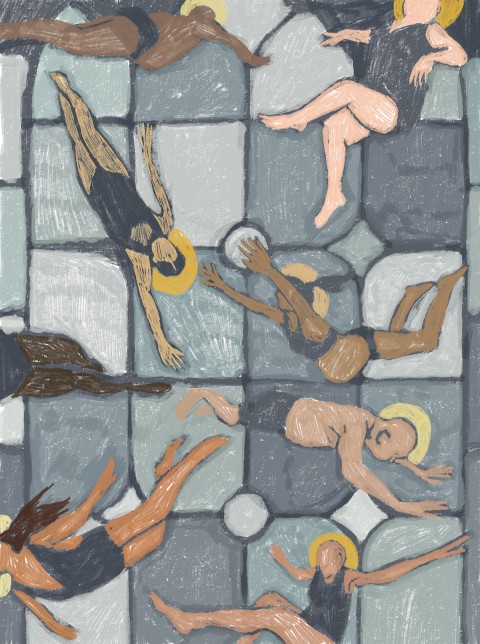

(Illustration by Martha Park)

I grew up in churches where the focal point was an unadorned, backlit cross high above the pulpit. Baptists are not big on images, but some do have a river scene painted above their baptistry in remembrance of Jesus’ baptism. Not ours. In our church, pictures were for Sunday school coloring pages and flannelgraphs. In the sanctuary, our imaginations subsisted on the Word and its echo in the words of hymns and sermons.

As a child, I went to my friend’s church from time to time. In her church, colorful statues and stained-glass windows depicted not just Bible stories but saints and martyrs. Though the cross in her church showed Christ perpetually suffering, I envied my friend. So many sights to puzzle over while puzzling words flowed from behind the altar. Something in me wanted to be fed through my eyes, not just my ears.

That hunger is no small part of why the Room of the Segnatura struck me forcefully when I first visited the Vatican in my late 40s. Such a feast for the eyes. The room was designed as a papal library where frequenters would read and reflect as their imaginations were saturated with its images. Now thousands of tourists pass through it, giving Raphael’s frescoes only a passing glance.