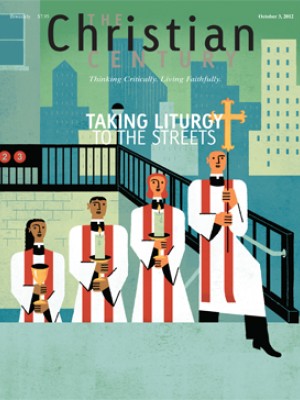

Worship without walls

Public ritual might be construed as a benign relic, as imperialism, or as marketing. Or it might be seen as a form of pilgrimage.

Many of us experience a special energy in worship when routine liturgical acts take place outside the church walls: processing around the block on Palm Sunday, offering ashes to strangers at a subway station on Ash Wednesday, attending a baptism at a public beach, or even simply gathering for or being sent from worship in a busy public place. The familiar becomes at least partly strange—perhaps uncomfortably so.

What contributes to this sudden strangeness? Can these acts teach us anything about Christian worship in general and its engagement with the wider world? Why worship out in public anyway?

It is increasingly unusual to attend worship in North America, and therefore to do so publicly is uncomfortable for some people. But all religious ritual is in a sense strange, and this strangeness is part of what generates ritual’s theological power. Imagine discovering someone intently tracing a large letter T in the air before a group of people; or someone repeatedly plunging another person under water without any apparent intention related to hygiene, play or malice; or people intently focused on taking one sip from a single, shared metal cup. These acts are curious because they appear intentional but do not have an immediately obvious purpose. Encountering them activates an imaginative search to solve the puzzle of what is happening in these acts.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The very strangeness of religious ritual—inside or outside church walls—becomes an invitation to the theological imagination: What is the meaning of that inscription in the air, and has it in some sense been traced on me? Is there something being cleansed in that immersion that I cannot immediately see? What power is in that drink to bring such attentiveness to a single sip?

Inside the church, the building itself assists in solving the puzzle of what a ritual signifies. In the most ancient house church yet discovered (Dura Europas in Syria), the community painted large stars on a midnight blue sky above the baptismal pool, ensuring that every baptism took place under a starry, predawn sky, in clear relationship with the full stretch of the cosmos. Beside the raised font is an image of what appears to be a stone sarcophagus with dimensions similar to those of the font, suggesting that the pool is like a tomb. Next to this image, nearly life-size figures of women approach with torches in darkness, suggesting images of the women who become witnesses to the resurrection and of the wise bridesmaids with their burning lamps. Thus members of this assembly, who perhaps themselves carried lights in the darkness when they came to witness the newly baptized rising from the font, were invited by the walls of the church to imagine themselves as something like witnesses to the resurrection and as wakeful bridesmaids leading the way into the wedding feast.

When such walls are stripped away, the strange nature of ritual is thrown into high relief: the significance of the ritual is no longer interpreted by the church’s physical structure but unfolds in a symbolically noisy public setting. The range of possible interpretations of the rite—and the number and diversity of interpreters—increases dramatically.

We might identify four ways that religious ritual that occurs in public is interpreted in the largely disenchanted culture of North America. First, the rites might be construed as benign relics of an outdated faith or a superstitious past. Second, the rites might be considered an imperialistic attempt by religious people to impose their views on what should be secular public space. Third, the religious activity might be understood through the dominant cultural models of business and marketing. In that view, the public ritual makes sense as a kind of advertising—an attempt to add members to a religious club—or else as a form of “liturgy to go,” an efficient way of providing goods and services to religious customers.

A fourth way of understanding ritual that takes place beyond church walls is to see such ritual not as a sign of irrelevance, nor imperialism, nor commercialism, but as a form of pilgrimage. Such ritual in public suggests that “there is another world, but it is within this one” (a saying sometimes attributed to surrealist Paul Éluard). The movement of worship outside the church building is a spiritual quest for “another city, whose architect and builder is God,” yet it is a city to be found within our local places and glimpsed through the kindling of the theological imagination by way of ritual. Rather than strictly dividing the world into believers and nonbelievers, a pilgrimage approach regards all people as potential seekers after the most true of worlds. This approach is well suited for our increasingly religiously pluralistic cultures.

Yet this approach enters the wider world vulnerably, having lost the interpretive power of the church walls. Given its vulnerability, several principles may serve as landmarks for such a pilgrimage.

Testimony to hidden realities: Poet Billy Collins locates his poem “Passengers” in the infamously mundane setting of an airport boarding gate, where he sits writing in a row of blue plastic seats “with the possible company of my death.” He observes among the “sprawling miscellany of people” the particular individuals whose lives, given “the altitude, / the secret parts of the engine, / and all the hard water and deep canyons below,” might be caught up together in death, and concludes that perhaps “it would be good if one of us / maybe stood up and said a few words, / or, so as not to invoke the police, / at least quietly wrote something down.” The poem longs to bear public, ritual witness to the unsung sacred nature of fragile, everyday mortality, but it recognizes that in our disenchanted cultures such acts are so strange that they might invoke not only the sacred but also airport security.

It is perhaps this same impulse that emboldens participants in the Ashes to Go movement to shrug off the risk of the police and head into city streets to offer to press ashes onto the foreheads of strangers on Ash Wednesday and to speak the ancient words, “Remember that you are dust, and to dust you shall return.”

A participant in such a liturgy in New York City, Mark Genszler, described the “wash of relief” that flowed over the faces of those who received ashes—a response he found partly surprising, as he had just told them that in addition to speeding toward the next subway stop they were more certainly traveling into death. But, he reflected, “if you share the secret of your mortality with someone else—even, or especially, a stranger—then you don’t have to pretend that you’re invincible.” The hidden vulnerability becomes at least momentarily public and honored as a holy mystery. And in any case, Genszler said, a shared burden may be lighter.

While on Ash Wednesday many Christians in Western traditions bear witness to the earthbound nature of human bodies, at Epiphany, in commemoration of the baptism of Christ, Orthodox Christians process outdoors to bear witness to the hidden character of earth’s waters at local lakes, rivers and seas in the Great Blessing of the Waters. On this day, every major body of water in the world is being blessed by the Orthodox. (Some have said that in Greece every puddle is blessed.)

Russian Orthodox theologian Alexander Schmemann writes that the Christian blessing of water—indoors or out—ought not be understood as making some water “holy” over and against all other “profane” water. Such a blessing would, Schmemann writes, render most of the world’s water “religiously meaningless.” Rather, he writes, the blessing of water is an epiphanic event in which the sacred character of all water is remembered and proclaimed through the prayer of blessing. This liturgical rite, complete with processional cross and fine vestments, often includes a celebratory full-bodied plunge into the water by members of the assembly, as if each local body of water is the Jordan River and the promised river of life.

Faithful Christian worship beyond the church walls bears testimony to another world hidden within this one. It names as holy mysteries not primarily what is esoteric or rare but rather what is shared, universal and partly forgotten: our bodies as “the earth we carry” (Augustine) soon to be laid down again, and the gift of water giving life to the earth and becoming for us a sign of the promised new creation.

Thanksgiving and beseeching: Every Sunday on the town green in New Haven, Connecticut, a eucharistic table on wheels forms the center of the Chapel on the Green, an outdoor gathering that begins with a half hour of an open drumming circle and concludes with the eucharistic table extending into a free lunch for anyone who is hungry, in a part of the city frequented by both the overfed and the underfed.

Deacon Kyle Pedersen described one man who danced his way across the green through the drumming session and into the Eucharist, embodying the spirit of thanksgiving through the hymns, psalm and Gospel. The only time he stopped dancing was during the intercessions, during which, Pedersen said, “he stood perfectly still and prayed out loud for his sobriety, for freedom from the addiction that had so powerfully grabbed hold of him.”

This liturgy made a public space literally resonant with two central patterns of Christian prayer, thanksgiving and beseeching, and so brought into the open prayers of both great need for healing and deep gratitude for blessings poured out and running over.

With years of experience worshiping on the green, Pastor Callista Isabelle knows how the outdoor setting has cultivated this pattern of prayer, especially in prayers for the interaction of humans and the wider creation. She heard more prayers about creation and weather in these services than in any liturgy held indoors. The prayers stretched out in thanksgiving for nurturing weather and in intercession for protection during harsh weather. The bodies of many of those praying are exposed to the elements not only during the liturgy but all night and day.

The pattern of thanksgiving and beseeching, what Don Saliers calls the “double helix” of Christian prayer, corresponds to a tension at the heart of Christian pilgrimage in the world: the world is seen (it is declared as an article of faith) as “very good,” while it is known (and attended to as a matter of conviction) as simultaneously groaning in travail, even crying out the accusatory question of why God has abandoned it. In both liturgy and everyday life, thanksgiving and beseeching become what Gordon Lathrop calls “a way to walk” on an earth that is both a miracle of abundant life and a crucible of unspeakable suffering. Liturgy beyond the church walls, at its most faithful, evokes such prayer and cultivates a spirituality for living in such a world.

A gathering wider than those present: Many protests against military imperialism are indistinguishable from one another, but the annual protest outside the gates of Fort Benning, Georgia, is striking. At its heart is an extended solemn chanted litany, sung in a procession of thousands, with each person bearing a white cross. From a raised platform, the leader sings the name of a victim killed by U.S.-trained forces in Latin America—“Irma Sanchez, six years old”—at which members of the procession raise their crosses and chant, “Presente!” For hours the names are read out, and the crosses—each inscribed with the name of a victim—are brought forward and placed on the giant fence erected to keep protesters out of the base that houses the infamous School of the Americas (now renamed the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation).

Father Roy Bourgeois, former marine and founder of School of the Americas Watch, says that the power of this annual ritual binds together the members of this disparate assembly: Sunday school students and teachers, recent immigrants, secular human rights activists, nuns and evangelicals. It also becomes for many, he says, a bridge across the boundaries separating Americans from the people of El Salvador, Bolivia, Guatemala, Argentina and Columbia. The communitas (to cite Victor Turner) generated by the ritual arcs out beyond the boundary of the assembly and connects in solidarity to distant peoples.

Father Bourgeois recalls Rufina Amaya addressing the assembly just before the procession. She is the sole survivor of the 1981 massacre in El Mozote, El Salvador, that killed hundreds of villagers, including her husband and three children. Attending to her quiet voice, the assembly of thousands was silent. Bourgeois says that through her presence and her voice, this “humble campesina” incarnated bonds that have extended far beyond the ritual event.

When liturgy travels outside the church walls, a band of pilgrims can cultivate living bonds of solidarity among those who might otherwise be strangers or even enemies. Such a procession is drawn outside by the spirit of humble solidarity expressed by the indigenous Australian activist Lila Watson: “If you have come here to help me, you are wasting your time; but if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.”

Agency: In Columbus, Ohio, a faith-based community organization identified a problem in the neighborhood: boarded-up houses owned by the city had become rat nests and crack dens, and the city refused to clean them up. One Sunday the local churches synchronized the ending of services (no small feat). Church doors opened at the same time and a stream of people poured into the street in procession. People came from the Catholic church, with incense and tall banners in the wind; from charismatic churches, with gutsy singing and handclapping; from the Lutheran church, with the pastor leading the way, playing trombone while people sang about the saints marching in and rats marching out. This river of people followed a processional cross, stopping traffic while neighbors waved and gaped. They marched to a block of boarded-up homes where they prayed, sang and called for the abandoned buildings to be cleaned up or torn down by the city, which owned them but refused to care for them.

The city maintenance crews arrived the next morning, so the event was a success. But the greater victory was that in a part of town not considered powerful, people knew their crucified neighborhood as also, at least for that moment, risen and still rising. At a similar event in another city, I heard a child express his experience in images resonant with the Spirit’s power at Pentecost: “I felt like a spark in a bonfire; so tiny and so powerful!”

When liturgy steps vulnerably into the world, when the stability or strength provided by the church walls is stripped away, the band of pilgrims may themselves become a sign of the strange, other world within this one, where the promises of scripture are being fulfilled: God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise; God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong . . . for God’s foolishness is wiser than human wisdom, and God’s weakness is stronger than human strength.

After such worship we might critically reflect: Are those who are despised in the world and counted as nothing now coming to know themselves as temples of God and experiencing the Spirit’s power? Do our processions share in the same Spirit and cultivate similar agency as those other processions that overcame the power of evil in Soweto, Warsaw and Selma?

A strange sign: Recently a woman named Christiane told me the story of an outdoor funeral procession in 1943 that became a living parable for the German village where she grew up. A young boy had accidentally drowned in a local lake. He had been a member of the Hitler Youth, and many members of that group came to the funeral in uniform, carrying Nazi flags. After the funeral, the procession was assembling to walk from the church to the cemetery. Christiane’s father, the local Lutheran pastor, assigned Christiane’s older sister, Gabrielle, 14 years old, to carry the cross at the head of the procession. He took her aside and said, “The cross will lead the procession; you must not let anything come in front of the cross.” The procession set out, led by the cross, followed by the pastor, the pallbearers and coffin, and then the mourners.

As Gabrielle carried the cross, she began to see people in uniforms with flags following her closely. She walked more quickly, but one boy with a flag matched her pace and attempted to pass her. She quickened her pace, and the pallbearers struggled to keep up. Gaps opened in the increasingly hurried procession. Soon, in order to stay at the head of the procession, she broke into a run with the cross. It had become, Christiane said, a race, with both the cross and the flags careening toward the grave. In the end, “my sister won the race; nothing came before the cross.”

For days afterward, the village talked and wondered about this sign. What had happened? What did it mean? A race between the cross and the flag, ragged gaps opening up in the church’s procession, youth and death swept into contention.

Having lived in the United States for decades, Christiane recently returned with her sister to visit their hometown, now part of Poland. The old Lutheran church is now a Roman Catholic church, but when they visited it they saw in the nave the same diminutive processional cross that had been carried in that long-ago procession to the cemetery, standing ready to be carried in the week’s coming procession. They stood before it and wept.

Christian worship outside the walls of the church unfolds in a setting in which many of the stabilizing patterns and symbols of the church building have been stripped away. Such events stand in some senses naked to the world, vulnerable, fragile and strange. The cross carried in procession is from the beginning such a sign: God’s power and wisdom hidden in what is apparently foolishness and weakness, a strange sign standing exposed to a wide public, its few words addressed to the world in Hebrew, Latin and Greek. In the theological imagination of the early church this sign also became the tree of life, bearing abundant fruit, its leaves healing and its branches sheltering, planted and flourishing in the most unexpected of places.

Our processions today outside church walls may be a similarly strange sign: bearing testimony to another world within this one, speaking of the world’s deep goodness and searing need in prayer, cultivating bonds of peace beyond our little gatherings, and in our weakness coming to rejoice in the Spirit’s power.