Junk food epidemic

Michelle Obama wanted to expand access to fresh, healthful food; Walmart wanted to expand into urban markets. When the First Lady and the retail giant got together last year to try to eliminate food deserts—low-income areas where there’s nowhere to buy fresh produce—many hoped this effort would put a dent in obesity and other public-health problems.

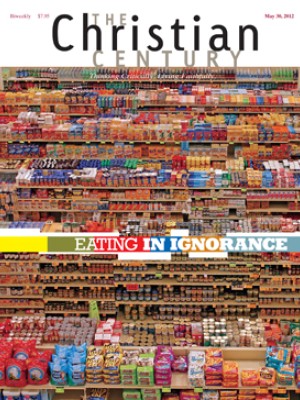

But recent studies have found little connection between food deserts and obesity. Whatever benefits a supermarket provides, improving people’s diet doesn’t seem to be among them. After all, even supermarkets offer more junk than healthful food—and the junk is more convenient, alluring and affordable.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Making healthful food available isn’t enough. People need to acquire the habit of eating well. Such habits are learned in families and communities. Forming good habits involves fighting unhealthful traditions (as Mississippi pastor Michael Minor is doing in banning fried chicken at church meals) and reconnecting to the land (see "Eating in ignorance"), as in projects that help children from low-income families grow vegetables. (This is an area in which Mrs. Obama has provided leadership.)

Public policy has a role to play as well. Exhibit A is the federal school lunch program. Public school cafeterias serve millions of low-income children on the taxpayer’s dime. Yet they have been thoroughly colonized by the fast-food industry, and even their unbranded meals are mostly prefab and nutritionally lacking. Some cafeterias are trying to return to making simple, wholesome meals from scratch. But they need support from school boards—and from Congress, which both drastically underfunds the school lunch program and blocks nutritional standards in order to placate junk food lobbyists.

The school lunch program is required to incorporate excess commodity food from the Department of Agriculture, which points to a second problem: the U.S. subsidizes the overproduction of grains and soybeans, creating a glut of artificially cheap carbohydrates, fats and animal proteins. To improve public health, fruits and vegetables need to be not just available but price competitive with the array of grocery-aisle junk the current system produces.

Here, too, community efforts play a role. Many farmers markets accept food stamps; some also offer income-based discounts. Farm-based gleaning programs are notable as well.

But the root problem, again, is bad policy. It would be a huge step if the government stopped propping up grain and soy bean production and used the money to subsidize vegetables instead—or simply added the funds to the school lunch program. But agribusiness exerts massive control over farm-state lawmakers. Though the omnibus farm bill is up for reauthorization this year, food activists are pessimistic about serious reform.

The junk food status quo is not the natural order of things. When general food shortages were a serious concern, the government stepped in with subsidies to make sure that farmers produced enough food. Today Americans face different issues and so require different policies. Families, churches and communities can take responsibility for local food cultures, but elected officials need to step up as well.