On December 6, 1876, in the tiny village of Washington, Pennsylvania, an Austrian-born immigrant named Baron Joseph Henry Louis Charles De Palm became the recipient of what is described as the first cremation in modern America. It was not a pretty sight.

For one thing, De Palm had already been dead for more than six months. He died in May in New York City, but finding a proper site for a cremation in 19th-century America was not a simple matter. Finally De Palm's friends located a crematory that Francis J. Lemoyne, an eccentric physician and radical politician, had constructed for his own use on his Pennsylvania estate. To preserve the body over this lengthy delay, De Palm had been primitively embalmed, first with an injection of arsenic and later with a sterner treatment of potter's clay and crystallized carbolic acid, with definitely mixed results. When the coffin was opened on December 5 for the viewing of the now badly shrunken and discolored corpse, some marveled that De Palm was recognizable at all. A queasy newspaper reporter gasped, "No spectacle more horrible was ever shown to mortal eyes."

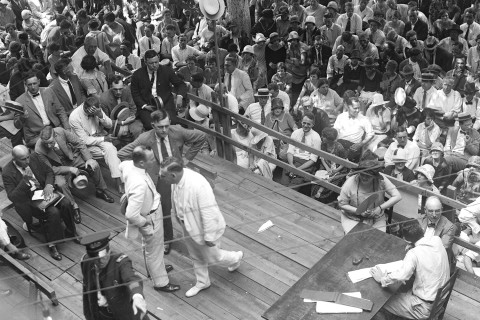

De Palm's cremation generated a three-ring media circus. Just before his death, De Palm had joined the newly formed Theosophical Society, a group of freethinkers and genteel social reformers, and, true to the Theosophical vision of that day, he left behind instructions to conduct his funeral "in a fashion that would illustrate the Eastern notions of death and immortality" and then to cremate his body. This was precisely the public relations opportunity the Theosophists needed to attract attention to their cause, and they set about making public ceremonies of both the funeral and the cremation.