My wandering mind: A pastor goes to yoga

Last summer, at the urging of a friend, I began attending yoga classes. When I said to family and friends, "I've started practicing yoga," my declaration prompted a variety of responses, mostly along the lines of disbelief or amusement. "What's so funny?" I finally asked one giggling colleague. "Well, it's just a bit hard to picture," she replied. "Face it, Martin, yoga is a meditative practice, and you are one of the least meditative people I know."

It's true, in a sense. I have a hard time slowing down. I usually do my meditation amid bustle and noise. To me, the two most dreaded words in the English language are silent retreat. So it's not surprising that the last time I exercised in a studio was during the aerobics craze in the 1980s. I loved bouncing around to funky tunes by Earth, Wind & Fire or the B-52s. The class felt like a raucous party featuring line dancing. It was nothing like what happens in a yoga studio.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Yet I tuned my heart to the slower rhythms of yoga rather quickly. All the poses of yoga are still so new to me, and the physical demands so challenging ("You want my body to do what?") that the routine hardly feels like a meditation. I have begun to imagine how it could be meditative, however, which has to be some kind of progress.

Among the thoughts that course through my brain when I'm supposed to be focusing on my breathing are thoughts about worship. Being a newcomer to yoga has prompted me to reflect on what it is like to be a newcomer to one of our services. In the yoga studio there are no crosses, crucifixes or stars of David. Instead I look at a statue of the Buddha, another of a Hindu deity and some crystals. Yet none of these symbols are referenced. Why are they there? What do they mean? No one ever says.

At our church we try to make newcomers feel welcome. We greet them, invite them to coffee hour and ply them with brochures about our church. It always pains me when someone comes to worship and leaves without meeting a handful of friendly people. As a newcomer to a yoga class, however, I want to slip in and slip out unnoticed. As an off-the-charts extrovert, this has led me rather belatedly to a basic truth: sometimes the friendliest thing one can do is to leave a person alone.

At the beginning of one yoga class, the teacher led everyone in a chant in Sanskrit. Everyone except me seemed to know it, perhaps not unlike when a visitor new to the faith hears the Lord's Prayer recited in our worship. I wondered what the yoga teacher was saying and whether, once I understood it, I would feel able to join in. Perhaps I would have to hold back because I couldn't affirm whatever she was chanting. For now, all I do is listen.

All the yoga poses have Sanskrit names, and other Sanskrit phrases are used in reference to I-don't-know-what. Sometimes the teacher translates the words into English. When she doesn't, I feel as if I've wandered into a Latin mass and hope that I can figure out when I'm supposed to kneel by watching everyone else.

The music played in yoga class is different from what I would listen to at home. There seems to be a lot of Enya, an Irish singer with an ethereal voice that I've always disliked. I know that the music is supposed to relax us, but I find myself distracted as I imagine listening to different music. I guess it'd be too much to ask the teacher to play some Marvin Gaye or Dizzy Gillespie. But surely a Chopin nocturne or a Bill Evans riff would be mellow enough. In one class the teacher mixed in music of pop singers Jackson Browne and James Taylor. I wondered if that change stirred controversy among the yoga students in the way that changes in music get people riled up in churches.

At the end of class everyone is instructed to lie still while the teacher offers what might be called a meditation (I'm sure there is a Sanskrit name for it). We are encouraged to focus on our breathing, or to inhabit our bodies differently, or to become in tune with our spirits. At these times, it's a disadvantage to have a theological education because I find my mind wandering: "This sounds like Gnosticism. Or Neoplatonism, at least." Then I ponder how these affirmations fit or don't fit into my theology. Then I wonder if newcomers to our church ask similarly skeptical questions when they hear me preach. Eventually I quiet my mind and just let the words wash over me.

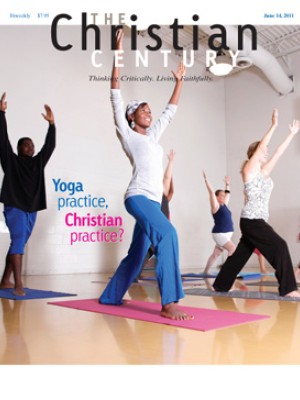

Yoga has also prompted me to consider some of the limitations of worship in our church. In our worship we declare the mystery of the incarnation. We also affirm the psychosomatic unity of all people—that is, that our bodies and spirits are not two separate realities but inseparably one. You would never know that from our worship, however, which tends to be from the neck up. For the most part, the only time worshipers move is when we stand up for the hymns.

We once had musicians from Nicaragua help lead our worship, and during one song they invited us to turn around in a circle. But there was not enough room in our pews to turn around without great difficulty, and most of us were in a quandary, feeling awkward and tense. How can we be incarnational in our worship when we cannot even turn around? In some ways yoga helps its practitioners experience the unity of body and spirit more fully than our current modes of worship do.

When I told someone that I had taken up yoga, she asked, "Oh really? What kind?" I replied with a self-conscious laugh, "There are kinds? I had no idea." I realize that my response exposed me as a rank beginner, one not able to make such distinctions. Sometimes I am on the other end of similar conversations. "So you're a Congregational minister, right? Is that really any different from Methodist or Presbyterian?" My usual response is something like, "Well, there are important differences—but none that you have to worry about."

So I guess I'm learning to meditate after all, even as I'm arranging my body into all kinds of new poses. Meditating about the church and our worship is a good thing. Besides, it helps distract me from my sore muscles.