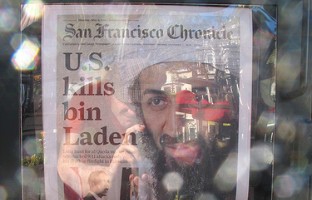

Justice or vengeance? The killing of bin Laden: The killing of bin Laden

"For

God and country. Geronimo, Geronimo, Geronimo!" These were reportedly

the words the commander of the Navy SEAL team uttered in signaling that Osama

bin Laden had been killed and his body captured. In a televised speech

announcing this news, President Obama asserted that "justice has been done,"

and he concluded with lines from the Pledge of Allegiance, along with a parting

"May God bless America."

Earlier

on the same day, the second Sunday of Easter, also known as Divine Mercy

Sunday, Roman Catholics and others around the world celebrated the beatification of Pope

John Paul II.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

I

write neither to cheer nor to jeer about either the killing of bin Laden or the

jubilant response by many Americans to his death. I pray that my identity as a

baptized Christian takes precedence when the ways of the nation—including

actions by the government and the military but also attitudes and activities

among many of my fellow citizens (and, alas, many fellow Christians)—are in

tension with the ways of God as revealed to us in Jesus Christ. Is the God

being invoked by the commander and the president the same God invoked during

the beatification ceremony? What kind of justice was done in the killing of bin

Laden?

Unquestionably,

bin Laden was responsible for terrorist acts of mass murder of Americans and

others, including fellow Muslims, around the world. Vatican spokesperson Fr. Federico

Lombardi, SJ, observed:

"Osama bin Laden, as we all know, bore the most serious responsibility for

spreading divisions and hatred among populations, causing the deaths of

innumerable people, and manipulating religions to this end." Nevertheless, as

John Paul II wrote

in his 1995 encyclical Evangelium Vitae

("The Gospel of Life"), because God "is always merciful even when he punishes"

evildoers, "not even a murderer loses his personal dignity, and God himself

pledges to guarantee this."

I

am well aware of how difficult it is to view a murderer as possessing dignity.

As a former law enforcement officer in both corrections and policing, I have

seen my share of evil. Yet there it is—the view that even murderers still

have some dignity is part of a cornerstone of Catholic teaching about the

sanctity of life rooted in our being made in God's image and likeness.

Accordingly, in

the Vatican statement, Fr. Lombardi added: "In the face of a man's death, a

Christian never rejoices, but reflects on the serious responsibilities of each

person before God and before men, and hopes and works so that every event may

be the occasion for the further growth of peace and not of hatred." I do not

expect all Americans to share this view, but I do hope that Americans who are

Christians allow it to shape their attitudes and actions.

Of

course, for many Christians this teaching does not mean that a murderer should

go unpunished or be allowed to continue to threaten people. Force may be used

to protect the innocent. But it must be justified and employed in

accordance with the criteria of the just war tradition.

Space

does not permit me to conduct an analysis of the war on terror or of every angle of this particular action. (Was it legal? Was it an assassination?

Was it the result of information gained through torture?) I'll focus on one

aspect that relates to the attitude of celebration on our city streets and university

campuses, and for this I'll turn to St. Augustine (354–430), who offered some

important lessons for Christians who claim to embark upon just wars.

Augustine

anchored the justice of war with God's divine will in creation, wherein God

created humankind to live in a just and peaceable community. Just wars are

supposed to restore and maintain a semblance of that tranquil order. The aim of

a just war—its right intent—should be to restore a just and lasting peace.

Augustine wrote,

Peace should be the object of your desire. War

should be waged only as a necessity and waged only that through it God may

deliver men from that necessity and preserve them in peace. For peace is not to

be sought in order to kindle war, but war is to be waged in order to obtain

peace. Therefore even in the course of war you should cherish the spirit of a

peacemaker.

He

argued that wars were justified to defend the innocent, avenge injuries, punish

wrongs, and to take back something wrongfully taken. He ruled out revenge and

vengeance, let alone mere retributive justice. Rather—and this is tied to his

understanding of right intent—his hope was to

have evil persons repent and reform, thereby restoring the peace. "We do not

ask for vengeance on our enemies on this earth. Our sufferings ought not

constrict our spirits so narrowly that we forget the commandments given to us.

. . . We love our enemies and we pray for them. That is why we desire their

reform and not their deaths."

Augustine

did not think that just war contradicted Jesus' injunction to love one's

enemies. Just war is a form of love in going to the aid of an unjustly attacked

innocent party; however, it is also an expression of love, or "kind harshness,"

for one's enemy neighbor. It aims at turning the enemy from his wicked ways and

toward making amends and helping him rejoin the community of peace

and justice. "Therefore, even in waging war," Augustine wrote,

"cherish the spirit of a peacemaker, that, by conquering those whom you attack,

you may lead them back to the advantages of peace."

But,

one may ask, how is this a benefit or how is it loving for those enemies who

are killed on the battlefield? Augustine replied, "Let necessity, therefore,

and not your will, slay the enemy who fights against you." According to the

latest reports, bin

Laden was unarmed when he was shot above the eye and in the chest—which

leads a number of commentators to question whether these lethal shots were

necessary. Split-second decision making by special forces personnel, as with

police, especially in the dark and in a building where hostile fire has already occurred, is indeed very difficult. If bin Laden had raised his arms in

surrender and still had been shot, I would call that shooting as unnecessary.

Augustine

added that a mournful mood should accompany even justified force. In his view, the "real

evils in war are love of violence, revengeful cruelty, fierce and implacable

enmity, wild resistance, and the lust of power," all of which would be at odds

with restoring a just peace. At the end of the day, even though he regarded

just war as congruent with Christian love, Augustine held on to the belief

that "it is a higher glory still to stay war itself with a word, than to slay

men with a sword, and to procure or maintain peace by peace, not by war."

If

the God that Augustine had in mind when he formulated these reflections were to

shape how we think about war, I doubt there would be much room, if any, for

celebrations about what has been said to have been done "for God and country."