Sunday, April 17, 2011: Matthew 21:1-11

On Palm Sunday we can answer the question, "Who is this?"

When he entered Jerusalem, the whole city was in turmoil, asking, 'Who is this?' The crowds were saying, 'This is the prophet Jesus from Nazareth in Galilee.'"

This is how Matthew's version of Jesus' triumphal entry into Jerusalem ends. Palm Sunday answers the crowds' question by declaring that Jesus is worthy of praise and worship. He is the King of Kings, the promised king, one who rivals Herod, the one whom the wise men visit, whose lineage can be traced back through the Davidic line to Abraham. Jesus is worthy of a grand entrance and of being the object of exaltation and glorification.

But although Palm Sunday used to be one of the major celebratory Sundays of the church year, with real palm branches waved by children ushering in our King, today it has almost been forgotten. Over time this celebration has given way to an emphasis on the somber reality of Passion Sunday, with a few palms thrown in for good measure. While there are good reasons for a dichotomous festival that bridges Palm Sunday and Holy Week, there are also good reasons for restoring Palm Sunday to its rightful liturgical place. After five Sundays of Lent and with the expectations of the week ahead, we could use a little revelry, a little pomp and circumstance, on Palm Sunday.

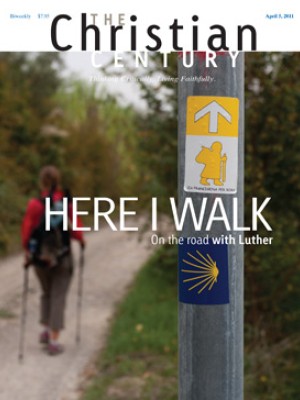

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

I don't meant to ignore reality or gloss over the events of Holy Week just because they are depressing. Rather, I want to propose that celebrating Palm Sunday can witness to our belief that the Jesus who will die on Good Friday is indeed the Christ, the Anointed One, the Messiah. The thing about Matthew is that Palm Sunday really works for this Gospel. Of course, there is the amusing detail in Matthew of Jesus riding on both a colt and a donkey. (Dear Matthew is all about the fulfillment of prophecy and trying to get his traditions right.) Of the four Gospel writers, it is Matthew whose portrait of Jesus as king is perhaps the most developed. Here is a Jesus who is immediately perceived as a threat to the throne, a danger to the established powers.

There is something quite poignant in the triumphal entry into Jerusalem as told in the first Gospel. The waving of palms, the scattering of cloaks upon the ground, the shouts of "Hosanna" are very public, unguarded and exposed expressions of belief. They're out there for the whole world to see, perhaps as much as the crosses on foreheads that began this season. Why is it that we publicly profess the suffering of the cross without hesitation but cannot easily express our praise and worship of the King of Kings? Have we liturgically endorsed suffering over celebration, affliction over adoration, even death over life? Have we tipped the scales to focus more on the ways in which the world tried to rid itself of Immanuel, God with us, rather than the means by which God's people continually witness to God's presence among us?

The misunderstanding is that Palm Sunday is simply a Sunday of adulation. This is not true. Jesus' triumphal entry into Jerusalem is just that--the arrival in the city where his fate will be decided and his future determined. To what extent might an emphasis on our celebration of Palm Sunday hold in tension God's reality and the world's reality? Might Palm Sunday be the occasion for suspense, not with the naive notion that we don't know what will happen, but with the acknowledgment of the tension within ourselves—that the Christ in whom we believe is the Jesus who died on a cross? Perhaps Palm Sunday can recapture the confession that we all must make at one time in our lives of faith: we can kill the King of the Jews, but we cannot take away his sovereignty. His governance has ushered in a reign where those who are blessed are the poor in spirit, the meek and those who hunger and thirst for righteousness.

Palm Sunday could be a moment of faith that happens too infrequently—a moment when we are allowed to feel the colliding of worlds and to experience a synchronization of who we think Jesus is and who God wants Jesus to be. It could be a moment when we sense, albeit only momentarily, not only that Jesus is worthy of our praise but also that our worship is integral to our relationship with him.

On Palm Sunday we can answer the question, "Who is this?" The remaining week in Lent will give us many ways to reflect on our reply—he is the suffering Messiah, the one who was crucified for me, the one who died for my sins. But on Palm Sunday we answer, "This is the King of Israel," my king, whose reign has not and will not be like the reign that is brought to light this week, and whose glory will conquer that which tries to crucify it.