Ordinary 19B (John 6:35, 41-51; 1 Kings 19:4-8; Ephesians 4:25-5:2)

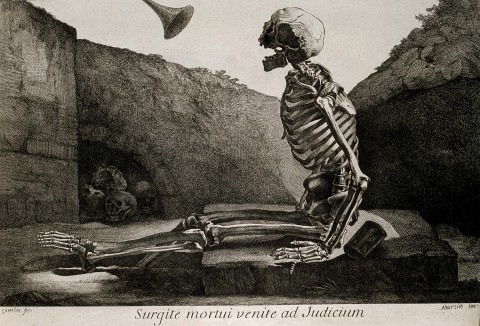

For decades, my students have failed to grasp the resurrection of the body as an article of faith.

The readings this week—John 6 and its dancing partner Elijah—invite our imagination into extraordinary places.

In John, the miracle of Jesus is not that he is born of a virgin—this man from Nazareth is the son of Joseph and an unnamed mother—but that he is from God. Since ancient writers did not know that mothers had eggs, providing half of what conception required, they wrote as if the essence of one’s identity derived solely from the father. So John calls Jesus a son of God the father. I recall Chaim Potok’s My Name Is Asher Lev: when Asher asks his mother what Christians mean when they say that Jesus is the son of the Ribbono Shel Olom (Master of the Universe), she responds, “I don’t begin to understand it.”

About an afterlife, John 6:44 says that we will be raised up on the last day. The New Testament claims that the end has already begun, for Jesus’ body has already been raised. I have taught university religion for 20 years, and no matter how I explain the resurrection of the body as an article of faith, students get it wrong on exams, the resurrection apparently being too bizarre for them to write out in a blue book. John 6:50 says that we will not die. This sounds like the Greek hope in the immortality of the soul—that something in us will not die but, like God, lives forever. Most of my students claim to have a soul, although they cannot define what it is. I am glad that this passage offers two ways to speak of our faith that life in God destroys the power of death.

John 6:41 is the first place in the Gospel that calls those who deny Jesus as Christ “the Jews.” By the year 95, considerable antagonism existed between those who accepted Jesus as Messiah, by then more gentiles than Jews, and the Jews who did not. What does this mean for us? Even in vernacular speech, the noun Jews has several meanings. You preachers have your work cut out for you, what with “The Jews” in John, God as “he” in Hebrew and Greek, slavery approved by God, women subservient to men, the three-tiered universe.

When encountering John’s over-the-top talk about eating flesh, I think of the Lakotas’ restored Sun Dance, where men who have vowed to suffer for the life of their people hang through the heat of the day by a cord that has been threaded under their skin, their pierced flesh symbolizing the arche typal human realization that all life is born through suffering. The author of Ephesians uses the same religious metaphor: our gift to God must be a fragrant offering, and from the sacrificial flesh presented to the divine comes life for the people. So Jesus hangs from the Lakota cottonwood tree, is burned up on a stone altar, and we consume his flesh to ingest the power of his life.

To help us imagine our eating the food of God, the lectionary offers the story of Elijah fed by the angel. I like that he is sitting under a broom tree. In scripture we find Abraham sitting under the oaks of Mamre, Deborah under a palm tree, Nathaniel under a fig tree, Zacchaeus up in a sycamore tree. Even Augustine was sitting under a tree when he heard the voice telling him to read the scriptures. We gather under the tree that we call the cross, its fruit available all year long, red drops of blood, and we drink its juice and so live.

Strengthened by the angel’s bread, Elijah walks for 40 days and 40 nights to the mountain called both Horeb and Sinai. Of course it is a mountain, for in many ancient societies the top of the mountain is where God lives. So in John 6 Jesus serves the meal of bread and fish to the multitude on a mountain. By the conclusion of the chapter, Jesus is teaching in the synagogue: from the law on Sinai to the assembly in a synagogue, these sacred places now make way for Christians to the Word of God whom we name Christ. How can we say this, respectful of those for whom Sinai and the synagogue remain places of divine encounter?

Forty days and 40 nights is always the waiting time: the rains of the flood, Moses on Mount Sinai, the spies scouting out Canaan, the taunting of Goliath, Ezekiel lying on his right side, the threat of the destruction of Nineveh, Jesus’ temptation, Jesus’ appearing after the resurrection—longer than a lunar month, the number of the weeks of human gestation, always 40.

Living deeply into the metaphors of the Christian faith is not for the faint of heart. You need an inspired heart, a flexible mind and even a steady stomach to read the Gospel of John.