Praying strings

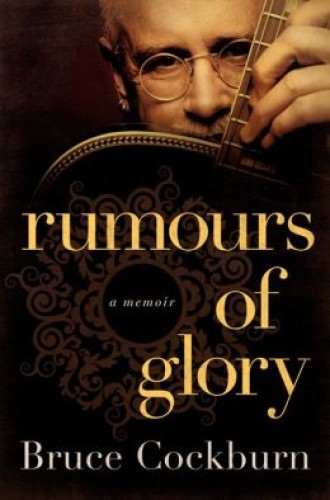

Some things generally known about the great Canadian singer-songwriter Bruce Cockburn: he’s recorded more than 30 albums of his jazz-rock-folk-pop songs, he’s a masterful guitar player (legend has it that when Eddie Van Halen was asked what it felt like to be the greatest guitarist in the world, his reply was “I don’t know, ask Bruce Cockburn”), he is eloquent about his own brand of mystical Christianity, and he is a passionate, well-traveled activist, especially for environmental causes and against wars.

Some things hardly known about Cockburn and revealed in his articulate, thoughtful, sweeping autobiography: he is an avid gun collector and enjoys shooting competitions; he has all his life been so reserved and shy that he still is uncomfortable with crowds, with pretending to be a star, and with being “open enough to allow another human beyond the courtyard of my heart”; he was so hapless musically as a child that his teacher gave him sticks to bang together in lieu of wasting an instrument on him; and at least twice he has been visited by a presence he believes to have been Jesus: “invisible to the eye but as solid and obvious as any of the people in the room. . . . I felt bathed in the figure’s energy. . . . The presence was real, male, and loving.”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Century readers may be most interested in Cockburn’s complex spirituality. He is a devout Christian who detests religiosity and fundamentalism, is enraged by violence in God’s name, and wanders into churches and chapels worldwide, hoping for peace and epiphany. Religion is no fixed abode for him (nor has he ever called one place home for long; he now lives in San Francisco). He is a wandering minstrel in the ancient tradition, but one able to reach many millions of hearts and souls in the wild new world of modern technology.

Born in Ottawa in 1945 while his doctor father was serving with the Canadian army in Germany, Cockburn early on fell in love with the wilderness, with books and ideas, and, at age 13, with the battered guitar he found in his grandmother’s attic: “my holy grail, the North Star and trail guide of my life.” By 19 he was an apprentice in his trade, playing in a series of bands in Boston and Toronto, and diving into the New Testament, which he had never really read as a boy, having much preferred the juicy murder and rape in the Old. He made his first record at the age of 24 and was almost immediately a star in Canada, where he is today something of a national treasure.

By the time he recorded his fifth album (Salt, Sun and Time), he was open and eloquent in public and in his lyrics about being “a follower of Christ, . . . the presence, . . . a male entity more fraternal than paternal, radiant with calm power, a savior showing up to save me because I’d asked.” With the album In the Falling Dark, a couple of records later, he began to speak bluntly about injustice and violence—the mistreatment of First Peoples in Canada, and then later of innocents in Guatemala, Nicaragua, Chile, Mozambique; the savagery and world-fouling scope of global capitalism; the epic sneer of the powerful at the endless screaming of the poor. In Rumours of Glory he says that he does not “write protest songs,” but “personal lament, a cry of spiritual anguish that arose from feeling helpless in the face of endless assaults against people and the land. . . . I want to paint sonic pictures of what I encounter, feel, and think is true.”

The virtues of Cockburn’s memoir are many. A great artist explains, more fully than he has in the 40-year chronicle of his lyrics, the tides and swirls of his fascinating life; a superb musician and songwriter delves a bit into how he works his craft, works with bandmates, is startled to compose by songs waiting to be written; an admirable and large-hearted man wields a sharp and eloquent tongue against greed and violence in religion, government, and business; a shy man learns, slowly, to open, and to love, and to come out from behind his façade.

I gobble up books by musicians, partly because I have not the slightest musical facility myself but know music to be the greatest of arts and am endlessly curious about how craft can become such a stunning and indeed holy thing. But most such books are flimsy ego trips or breezy ghostwritten mush. I have read only two beautifully written and piercing memoirs of this sort: Bob Dylan’s Chronicles: Volume 1, and the great Australian rocker Paul Kelly’s How to Make Gravy. Bruce Cockburn’s book now joins that august company for me, and it has the additional and substantive quality of being uniquely thoughtful and eloquent about the author’s Christian faith and how it informs his life and work.

Prayer is “a way of breathing and seeing,” Cockburn writes:

of caring, a means of giving thanks and opening the mind and soul. . . . The Divine is there, no matter what the ism. . . . The Divine infiltrates our being and manifests, as it must, through the electrochemical processes in our brains. . . . God is the matrix in which we move, if we were only aware of it. The Divine touches us. We feel it as a species. We hunger for it. Sometimes we run from it. A distortion occurs when the gifts of God are translated by cultural gatekeepers, . . . seek to usurp divine power, make it their instrument, and crown themselves God’s regents . . . brutal deeds done under the banner of God, fueled by men’s ego, greed, and fear, . . . [but] from the first to the last we are all one in the gift of grace, and if we hold this gift dear we can be whole again.

Or, as this master songwriter and composer once wrote in a song, “God waves a thought like you’d wave your hand / and the light goes on forever.”