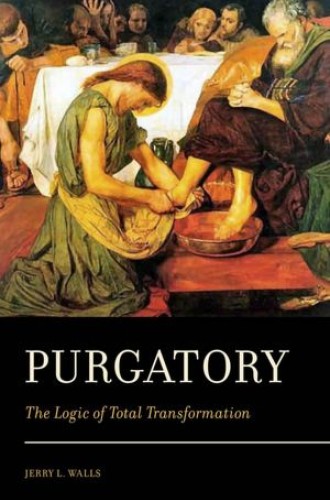

Purgatory, by Jerry L. Walls

Can Protestants believe in purgatory? Should they? Might agreement on purgatory enhance ecumenical relations between Catholics and Protestants? These are some of the questions Christian philosopher Jerry L. Walls addresses, and his answer to all of them is yes—much to the chagrin, no doubt, of many conservative Protestants and to the delight of many progressive Catholics, Walls argues that purgatory is biblically permitted, if not explicitly biblically taught, and that it is reasonable to deduce its existence on the basis of universal Christian convictions about the nature of persons and of heaven.

Walls is a Wesleyan philosopher who has written extensively on eschatology. His books Hell: The Logic of Damnation and Heaven: The Logic of Eternal Joy are widely discussed philosophical treatments of these subjects from an evangelical perspective.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Walls’s main conclusion is summed up thus:

Critics of the doctrine often have a tendency . . . to depict it as a matter of salvation by works and then to reject it highhandedly in the name of grace. However, to pit purgatory against grace is to fail completely to grasp that purgatory itself is very much a matter of grace.

He admits that some traditional accounts of purgatory, especially those produced by medieval Catholic writers, focus on punishment to the detriment of grace. However, he demonstrates that contemporary Catholic theology, including that of Benedict XVI, has substantially altered the purpose of purgatory so that it is now generally understood as an opportunity for sanctification rather than for satisfaction of God’s justice.

Purgatory includes a meticulous account of the doctrine’s history. Walls gives the most attention to Dante’s vision of purgatory, which he finds ambiguous and sometimes inconsistent, and to C. S. Lewis’s idea of it, with which he seems to be in complete agreement. Walls also discusses purgatory as a postmortem opportunity for salvation for those who would have accepted Christ in life but who for whatever reason were not able to.

Walls’s basic reason for asserting the existence of purgatory is the character of God. Surely a God of love who wills the salvation of all people and who wants even the already saved to be transformed totally into Christ’s likeness would make provision for such salvation and transformation beyond bodily death. This summary of his reasoning, however, does not begin to do justice to the subtleties of his arguments.

Walls does a very good job of dispelling many Protestant and Catholic caricatures of purgatory. For him purgatory is not for the punishment of sins, and belief in it does not take anything away from the doctrine of salvation by grace alone. Still, he may be expecting too much of Protestants to suggest that they adopt a term loaded with so much medieval baggage.

The author ably demonstrates that Catholic imagery of purgatory has evolved over the centuries until now it is understood to involve something more akin to continuing spiritual formation than to hellish suffering. And he mentions several notable Protestant theologians who have believed in purgatory, without the medieval imagery or the aspect of punishment for sins. Among them are the turn-of-the-century British theologian P. T. Forsyth and Clark Pinnock of a century later. He also offers reason to think that evangelical Donald Bloesch believed in something like purgatory.

The most notable example Walls offers of a Protestant who openly embraced a version of purgatory is that of C. S. Lewis. For Lewis, hell, in the intermediate state, turns out to be purgatory for those who leave it for heaven, which Lewis thought was a rare possibility. In some of his writings it is apparent that he expected to spend time in purgatory, in which case he portrayed it as a kind of educative process preparing a person for the beatific vision of glory. That’s Walls’s idea of purgatory.

Walls’s main argument is intuitive: we know that the vast majority of believing sinners, justified by grace, die with sinful dispositions. Heaven is a place of perfect holiness; sin cannot exist there. Purgatory is whatever process forgiven people go through, whether lengthy or short in duration, to become the kind of person who can enter into God’s presence. It is the completion of sanctification.

Fortunately, Walls does not offer his version of purgatory as dogma or even doctrine. It is what theologians have called theologoumenon—opinion put forth for discussion. Clearly his own mind is settled about it, but he is not advocating a new doctrine for Protestants to confess. He’s offering his opinion for consideration. And he makes a good case for it. However, I would not call what he is describing purgatory. I would call it heavenly preparation for the complete and direct face-to-face encounter with God. And I would argue that if Protestants embrace the concept, they should admit that we cannot know how long the preparation takes or what it involves except that it is a work of the Holy Spirit and not of human achievement. Many Catholics can agree with that.

One aspect of Walls’s belief about this postmortem process, whatever it should be called, is that it is completely voluntary. That is, a dying believer will want it and will cooperate with the Holy Spirit in it. If it involves some kind of suffering, that suffering will be welcomed. Walls refers to the one bus rider in Lewis’s The Great Divorce who chooses to stay in heaven. The man allows an angel to remove from him a giant lizard—lust. The removal is painful, but the man is glad for it.

Most Protestants will resist any idea labeled purgatory and probably any notion of a sanctification process after death. They believe that God completes their readiness for heaven instantaneously when they die. Walls is simply arguing that for most people the preparation takes some time. If Protestants can stretch their minds to accept his reasons for that, they may be willing to accept his view of the afterlife, even if they never refer to the intermediate stage as purgatory.