Blessed and dangerous

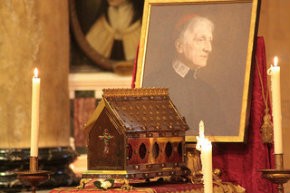

What might be called the year of John Henry Newman has come and gone with a flurry of books devoted to the former cardinal. His beatification—the last stage before granting full sainthood—was conferred by Pope Benedict XVI in September 2011 at an outdoor ceremony in Birmingham, the city where, from 1848 until his death in 1889, Newman did most of his work after becoming the most famous convert to Roman Catholicism in the 19th century.

The prospect of Newman’s being raised to the altars as the Blessed John Henry has not pleased all Catholics. Garry Wills called Benedict “a dissembler and disguiser” for praising Newman as “a model of submission to church authority.” For Wills, Newman was a testy rebel against Vatican obfuscation and authoritarianism until, in 1881, the newly consecrated Pope Leo XIII “bought him off with a cardinal’s robes when he was eighty and tamable.”

The recent spate of books on Newman shows that there is little hope of settling all arguments about Newman or about Benedict’s understanding of him. Yet one matter can be set straight: Newman’s entry into the Church of Rome hardly turned him into a lapdog of the Roman curia. One 19th-century Vatican monsignor was quite alarmed by Newman’s alleged “radicalism”—his stress on the primacy and inviolability of conscience, his insistence on fairly viewing all sides of a controversy, his open criticism of the papacy, his argument that Christian doctrine is not ahistorically fixed but historically developing. These accumulated “heresies” prompted the prelate to call Newman “the most dangerous man in England.” He also recommended that Newman be “crushed.”