Right-wing roots

The scholarly quest to discover the roots of the religious right has already passed through several iterations. The first task was to expose what I have called the abortion myth: religious right leaders' self-generated fiction that their moral outrage over the Supreme Court's 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling bestirred them out of their apolitical torpor and galvanized them into a political movement.

The facts tell a different story. At their meeting in 1971, delegates ("messengers") to the annual gathering of the Southern Baptist Convention, hardly a bastion of liberalism, passed a resolution calling for the legalization of abortion, a resolution they reaffirmed in 1974 and again in 1976. When the Roe decision was handed down, several evangelicals, including the redoubtable fundamentalist W. A. Criswell, applauded it as marking an appropriate distinction between personal morality and public policy. Only later in the decade, following the 1978 midterm elections and the circulation of a film series called Whatever Happened to the Human Race?, which featured Francis Schaeffer and C. Everett Koop, did evangelicals embrace what they had previously regarded as a Catholic issue.

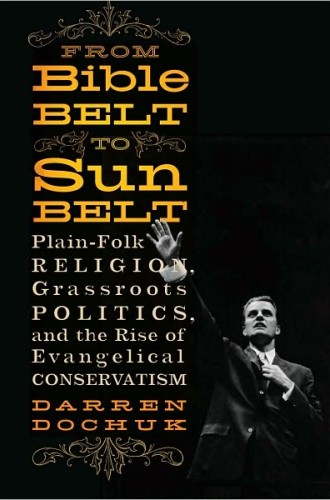

Having dispensed with the abortion myth, a second generation of scholars has peeled back additional distortions to reveal the deeper historical impulses that would come to the fore in the late 1970s. Steven P. Miller's Billy Graham and the Rise of the Republican South examines the complicity of the 20th century's most famous evangelist. For good and obvious reasons, some historians, such as Lisa McGirr in Suburban Warriors: The Origins of the New American Right, have trained their focus on Southern California, especially Orange County, as a kind of petri dish for political conservatism.