Sundown Towns

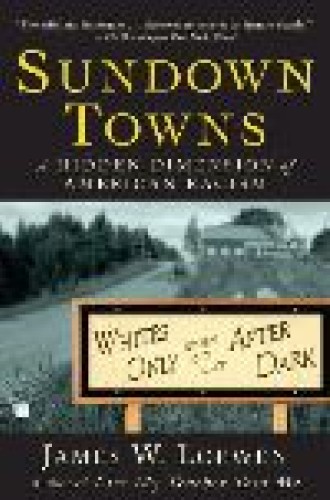

The horror of ethnic cleansing may seem a dreadfully common part of today’s global news stories, but America’s own history of ethnic cleansing is still waiting to be told, James Loewen contends. In Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism, Loewen exposes, explores and explains the forceful establishment of towns, cities and suburbs that would not let the sun go down on African Americans—and in some cases not on Jews, Chinese Americans, Mexican Americans or Native Americans either.

In the same decade when the German government took down its embarrassing “Jews Not Wanted Here” signs in preparation for the 1936 Olympics, Loewen notes, U.S. officials tacitly accepted and sometimes warmly embraced the presence of hundreds or thousands of similarly menacing signs: “N___, Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on You in ________.” It is our collective comfort with this piece of our racist past that troubles Loewen most. It should trouble more of us as well.

Loewen, a Harvard-trained sociologist who has taught at Tougaloo College and the University of Vermont and whose books include Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong (1995) and Lies Across America: What Our Historical Markers and Monuments Get Wrong (1999), relishes the role of iconoclast and exploder of treasured myths. Much of what he recounts in Sundown Towns is not news to historians, despite his repeated claim to the contrary, but he is certainly correct that most white Americans know little about the enormity of this history.

If Loewen’s anger over injustice is evident, his telling is far from a simple rant. Sundown Towns presents the subtlety and complexity of America’s twisted history of race, the relationship between sundown and nonsundown jurisdictions, and the ways white residents explained their segregated lives and justified the exceptions that embodied the rule.

Sundown towns were largely a northern phenomenon. In the South a humiliating system of Jim Crow social segregation was possible, but demographics in most parts of that region meant that communities were too dependent on African Americans to engage in the kind of ethnic cleansing that characterized significant sections of the North (there were at least 472 sundown jurisdictions in Illinois alone, Loewen believes). By the mid-20th century the phenomenon of sundown suburbs—Loewen explores the region around Detroit, among others—shifted the practice into another key, drawing legitimacy not only from earlier court rulings that had upheld sundown ordinances and restrictive covenants (which forbade homeowners to sell their property to members of certain minority groups), but also from Federal Housing Administration policies that supported neighborhood “stability” over equal opportunity.

Loewen’s presentation provides context for understanding the story of my own town, Goshen, Indiana (which the books mentions twice, but only in passing). Typical of sundown communities, Goshen was a northern city that had had some African-American residents in the 19th century before sundown towns began to emerge after about 1890. In the years following the Civil War, emancipated slaves had settled all over the United States. But around the turn of the 20th century, town after town, especially in the Midwest, forcibly—and sometimes lethally—expelled its African-American residents. Neighboring jurisdictions might then assert sundown sentiments to make it clear that blacks fleeing other places should not relocate there.

Unlike some other Indiana municipalities, Goshen never had a citywide ordinance banning black residents (although a good number of home deeds there bore restrictive covenants, which the U.S. Supreme Court declared unenforceable in 1948). Legislation, racist signage and violent expulsion were methods of the most egregious or desperate sundown communities. But, as Loewen explains, astute chambers of commerce, politicians and newspaper editors often managed racial customs in other ways and cast them in other terms. From 1939 to 1955 the self-description in Goshen’s city directory remarked that “crime has been reduced to a minimum, and contributing in a large measure to the absence of crime is the character of the population—97.5% native-born white, 2.5% foreign-born white, and no Negro population.” From 1957 to 1978 the sentence appeared without the final four words, but with the meaning still intact.

Such was the mood that when Marian Anderson twice sang at Goshen College during the 1950s but spent the night in nearby Elkhart, many residents instinctively believed that she had been denied lodging in Goshen. In fact, all of the white performers in the college arts series stayed in Elkhart too because the college did not think either of Goshen’s two modest hotels worthy of acclaimed guests. But the fact that Anderson’s stay was so readily interpreted in this way points to the city’s sundown sentiments. And indeed, a poll of the town’s two hotels and four other overnight establishments conducted in February 1961 by the Goshen News revealed that only one manager “indicated that a Negro had recently been given overnight lodging.” The others were either forthright about their denial of rooms to African Americans or hesitated to disclose their policies.

By the time the first black professor arrived in 1969, and a black postmaster in 1977, public mores in Goshen were beginning to change, again in line with Loewen’s national chronology. By about 1980, he shows, most sundown towns had caved in (though a few new sundown-style suburbs and gated communities were springing up). However—and here Loewen’s analysis is especially insightful—this quiet revolution occasioned no public acknowledgment, no reckoning with the past, no effort to expose the truth and pursue reconciliation. Thus our sundown legacy still haunts and hurts us.

That complex legacy includes a tendency to frame race as a puzzlingly elusive problem, and one for which whites have no responsibility. As early as 1951 a Goshen College sociology student who was curious about why none of the county’s African-American citizens lived within the borders of the county seat had noted that when he asked people if they thought there was a problem of prejudice in Goshen, nearly all said that they were “aware of no problem because there are no Negroes living here.” Loewen explores the assumptions behind such statements in a substantial chapter called “The Effect of Sundown Towns on Whites.”

Facing our common past is the first step toward a remedy, Loewen asserts in the final chapter. But what shall we do with this knowledge? To his credit, Loewen offers a number of suggestions for moving neighborhoods and towns toward integration, ranging from raising uncomfortable questions in public forums to pressing for major new legislation. He also challenges the contemporary assumption that with the formation of virtual communities in cyberspace, physical place and proximity no longer matter.

The book relies on a host of black voices to document sundown practices, but Loewen does not address how these people and similarly excluded Americans have survived and thrived, what kind of a future they envision and how they want to get there. In his unmasking of a hidden aspect of white American history, Loewen ended up telling a story driven by white actors. As we move toward some reckoning with and remedy for America’s experience of ethnic cleansing, we would do well to continue the work of storytelling that Loewen has begun—making sure that those who have been and often still are marginalized can share their stories and visions and have a role in directing all of us who take up this common task.