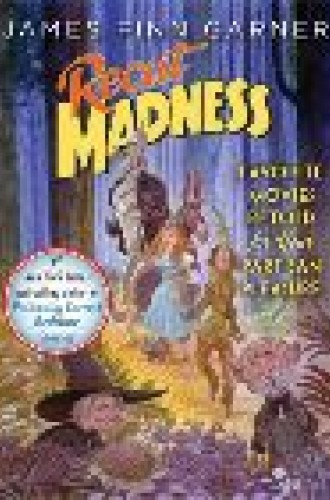

Recut Madness

If Abe Lincoln were to once again borrow from Jesus—but for C-SPAN’s cameras—he might say, “A house divided against itself cannot stand each other.” Partisan rancor is everywhere, leaving a few brilliant minds—Stephen Colbert, Jon Stewart and Bill Maher among them—to revel in and play with the fray on TV.

Joining them in print is author James Finn Garner, whose latest book shares a sharp humorous kinship with his 1994 New York Times chart-topper, Politically Correct Bedtime Stories. Whereas that tome took a dozen fairy tales and recast them for the soft, too-sensitive 1990s, Recut Madness imagines what classic cinema might look like from a strictly Red State or Blue State perspective. So we get Tom Joad in The Grapes of Wrath coming to this epiphany: “If I jus’ keep listenin’ to the fellas on the talk ray-dio, it should all make sense some day.” Or Alex in A Clockwork Orange, rehabilitated as a chic Blue Stater, “in his Dockers and L.L. Bean sweater, happy to be escaping confinement and strangely craving a tall skim latte half caf, half synthemesc.”

Sometimes the parody takes on a politically charged film itself, as when Garner’s narrator becomes a crotchety Republican interpreting Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth: “Now some boring guy in a blue suit is giving some kind of PowerPoint lecture on rising ocean levels and severe tropical storms. Hello! Alert to the obvious: No one likes cold weather!” And weaving a crazy-quilt thread through it all is “The Wizard of Dubya,” a six-part story interspersed through more than three dozen chapters (“Dubya” was Garner’s original concept for the book). The president appears as a Scarecrow who works for the Heartland Defense Anti-Crow Project and as a donkey who sings “If I Only Had a Spine”: “If you ask me what I’m thinkin’, I’ll stand there dumb and blinkin’ / Then check the New York Times.”

Garner, of course, deals in time-honored stereotypes: Democrats are indecisive, sensitive and soft; Republicans are rigid and macho and march in lockstep. But by pasting cardboard cutouts into well-loved movies, Garner accomplishes two things. First, he creates scenes that suggest what might happen if actors and directors were held hostage by brainwashing political action committees. And second, he puts his finger on the pulse of a social ill that sorely needs laughter as its best medicine. What runaway political correctness was to the 1990s, partisan politics is to our times.

Capping Recut Madness is a list of “recuts in development” that invites readers to let their own imagination loose: “Willy Policy Wonka,” “Honey, I Shrunk Our International Standing,” “Dial M for Mass Transit,” “Saving Private Retirement Accounts,” “Commie Dearest.” Throughout the book, Garner maintains a lively bounce spiced by sharp one-liners and a focus that stays fixed on the overarching theme. At a time when political peace talks look about as likely as getting a duck elected president, Recut Madness at least allows donkeys and elephants to laugh loud and hard together—or, if they so choose, separately.