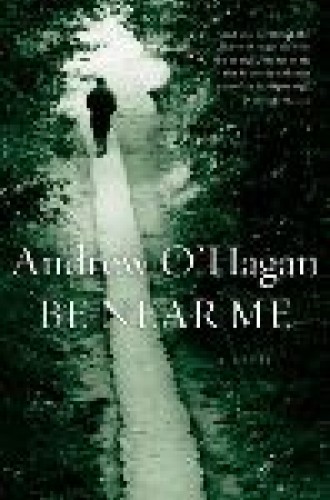

Be Near Me

This is a book I should not have liked. It’s a story of a lonely Catholic priest trapped in a bleak little parish in a nowhere Scottish town. Of course the priest is sexually repressed and socially inept, and of course his downfall is a chaste kiss plastered on a teenager under his care. It’s a hackneyed plot that’s no longer news. Yet to tell that story, and to tell it with lyrical persuasiveness, to actually make us feel more than pity for the priest, to show us the complexity of a life that we might dismiss as that of merely yet another priestly pedophile, is the wonder that beckons us into Andrew O’Hagan’s third novel.

As a bishop, it’s part of my present vocation sometimes to listen to stories of those who fall from their high churchly vocation by means of some unimaginative sexual misdeed. It is difficult to retell such stories well—their grubby, sordid banality makes cliché almost unavoidable. Add to that our society’s decidedly anticlerical, antichurch prejudice that renders suspect much of the media’s moral indignation and its gleeful accounts of the descent of priests, and who needs another novel about this topic? The stories of those who would betray their priestly vocation for a kiss are predictable and prosaic.

Which makes all the more notable what O’Hagan has wrought in Be Near Me. This is decidedly not just another novel about another priest groping another teenage boy. For one thing, O’Hagan is a wonderful writer. He employs such solid, understated, yet quietly lyrical prose that one fears that one likes the characters simply because O’Hagan writes about them so beautifully. I resisted his art at first, feeling that I was being enticed into friendship with people who would eventually deeply disappoint and in the end not be worth the effort. Is O’Hagan describing their essentially trite lives in a way that is almost too poetic, too graceful to ring true? Is he attempting to romanticize as victim a perpetrator of abuse? Yet then I realized that I genuinely cared about the characters because they are so believable, deep, true and even lovable.

Father David Anderton is, by anybody’s estimate, more interesting as a person than as a priest. It is difficult to figure out why he became a priest in the first place, except as a way of not having to make a life for himself. God plays, so far as I can tell, no role in Father David’s life or in this novel. God, like the reader, watches helplessly as Father David curls deeper into himself before lunging at a teenager in a last ditch attempt to have a life. He seems to have gone into the priesthood as a result of his vague, sentimental, neogothic student experience at Ampleforth, a prestigious Catholic boarding school. Father David is Kierkegaard’s aesthete through and through, treating life as a series of aesthetic experiences, inchoately felt, never actually engaged. (Back at boarding school he once asked one of his teachers, “What is more important to the world, ethics or taste?”) Perhaps O’Hagan is suggesting that those who are unable to be passionate and engaged with other people are also inept at letting God love them.

Father David serves the forlorn Scottish parish of Dalgarnock, dutifully going through the motions of being a priest without seeming to notice that his life is a sort of lie; Dalgarnock is a long way from the archaic tinting of Ampleforth. In Father David’s fateful 57th year, his unspectacular, repressed and drab little life stunningly unravels. He befriends a couple of beer-guzzling, drug-taking, profane teenagers, Lisa Nolan and Mark McNulty. Mark stupidly wants no more from his future than a fast car and a willing woman. In Father David’s romantic imagination, the boy is worked up into a wonderfully unbridled primitive who reminds the priest of his still-missed and beloved Conor, a boy with whom he had a fling while they were students at Cambridge.

Early in the story, Father David says that Mark

behaved as if the world was invented just for him, and his face was serene enough to convince anyone who looked at him that things would be all right if one stuck close. I think in our hearts we believe that beauty is a very sincere kind of knowledge: we fall for the wisdom of beautiful lips no matter what they are capable of saying. Mark knew it. He knew it the way a bird might know where to fly in winter.

It is more romantic sentimentality loaded upon the limited Mark than he can bear.

When Father David and Mark spend a night roaming about town and whooping it up under a train trestle, it is one of the most wonderful evenings of the priest’s life. Just before dawn, at the manse, he kisses, or attempts to kiss, Mark.

Earlier Father David had predicted that there are moments in which “our lives are liable to catch up with us.” His life catches up with him when his housekeeper, Mrs. Poole, walks in at the precise moment of the kiss. The police come and arrest him, a mob of the town’s Protestant Orangemen destroy his car and threaten a lynching, the manse is gutted by fire, and Dalgarnock’s newspaper broadcasts the headline “English Priest in Ayrshire Kiddie Abuse Scandal.” But on the way to that fateful plunge, we have been drawn into and have learned to care for Father David’s life—so much so that we realize that the stolen kiss and the priest’s conviction are not the whole story that O’Hagan wants to tell us.

The novel’s title is taken from a stanza in Tennyson’s “In Memoriam” that is the book’s epigraph: “Be near me when my light is low. . . . Be near me when the sensuous frame / Is rack’d with pangs that conquer trust. . . . Be near me when my faith is dry.” Father David embodies Tennyson’s words—a sentimental, self-absorbed, romantic plea arising out of his plaintive, dreamy life.

The no-nonsense, plainspoken Mrs. Poole is the most interesting character in the novel. We like her the moment she first bustles into his study to rearrange the dust while making pronouncements and displaying her prejudices. Mrs. Poole’s feet are firmly planted on the solid soil of this earth. Strong, opinionated and dutiful, only she seems capable of actually living what fate has dealt her—even though she has known much real sadness and is dying of cancer.

In a way the novel, in its delicate beauty and in its juxtaposition of Father David and Mrs. Poole, is a caveat on the perils of a life lived in Tennysonian romantic, aesthetic sentimentalism. Mrs. Poole alone tells Father David the truth about himself. He is a man, as Mrs. Poole says, who is a “clock with many faces.” While he yearns for affection, he never gets around to actually connecting with anyone. He misses the father he never really knew and is an enigma to his pulp-fiction-writing mother. Neither really English nor really Scottish, not actually a believer or a disbeliever, of uncertain sexual disposition, Father David acknowledges early in the novel, “I’ve never been sure I belong anywhere in the world.”

In the end, Mrs. Poole offers Father David the only grace that comes his way on his descent to oblivion. “It’s not a crime not to know yourself,” she tells him. “It’s not a crime to send life away. It’s just a shame.”

Father David confesses to his bishop, “I think I used the Church. It was a beautiful hiding place. I’m sure it has been for others.” Perhaps this is a story about the perils of attempting to be a priest. It is a great risk being enmeshed with God’s sinful people without being convinced God put you there. The church is not the hiding place that Father David hoped it would be. Perhaps this is also a warning about the dangers of being before people at the altar as a vicar of Christ without having attained some degree of self-knowledge and self-possession.

Perhaps. But O’Hagan seems to write without moralizing intent. Be Near Me is a delicate, beguiling, poetic novel, an honest depiction of lives intertwined on their way down. With just a few adept strokes, O’Hagan renders a complex portrait of people who are under the gaze of God without ever being touched by God. A quiet beauty, an understated stream of yearning and regret, flows through every page. Rarely has the fall of a priest, the mess of a life hardly lived, been so beautifully told.