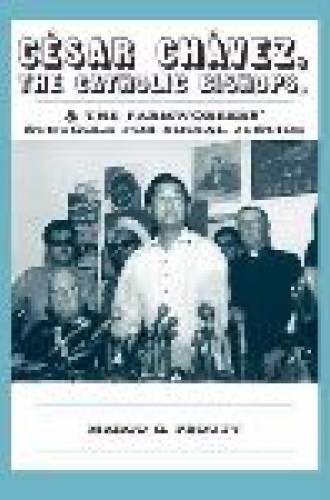

César Chávez, the Catholic Bishops, and the Farmworkers' Struggle for Social Justice

Next to Martin Luther King Jr., César Chávez was the most important Christian social activist in recent American history. His commitment to nonviolence lent moral credibility to his leadership of the farmworkers movement in the 1960s and 1970s. Since Chávez was a Catholic, Marco Prouty asks: What was the connection between the Catholic bishops and the social-justice aspirations of Mexican-Americans during the civil rights era? The answer is disappointing for advocates of social justice. Notwithstanding the large body of Catholic social teaching and despite the determined efforts of Monsignor George G. Higgins (the main hero of Prouty’s book), much of the hierarchy of the church remained socially conservative and was reluctant to support Chávez and the farmworkers in their strikes and boycotts.

Prouty is ironically correct that precisely because the Catholic Church did not support Chávez very much or very well, it was in a position to be a broker between workers and growers about eight years after the strike began. But he seems unaware that the workers’ union would no longer have been viable by the time the Catholic Church got around to supporting Chávez were it not for the truly heroic efforts of Protestants from the time the strike commenced in 1965. Prouty does not discuss the real hero among those who helped Chávez: Chris Hartmire, a Presbyterian minister and longtime director of the California Migrant Ministry. If the Migrant Ministry had not been there early and constantly in support of la causa, the growers would have beaten down the campesinos as they always had done previously.

I am also perplexed that a book published in 2006 fails to take note of excellent recent scholarship, especially the work of Gastón Espinosa and Virgilio Elizondo on Latino civic engagement and a new biography of Chávez by Dan La Botz. Engagement with both would have improved Prouty’s work.

This is a sad story. The farmworkers of the Southwest are still among the poorest paid and least visible workers in the U.S. The Catholic Church, with its great strength, could have made a difference. Its reluctance to support for Chávez until 1973 and its virtual abandonment of him after 1976 are perhaps part of the reason the growers have largely won, leaving the workers without substantial protection. There are today few voices to protect American farmworkers from the unfair competition of the guest-worker program advocated by President Bush and Senator McCain. The “least of these,” those who bring food to our tables, deserve better both now and in the histories of their struggle for dignity and justice.