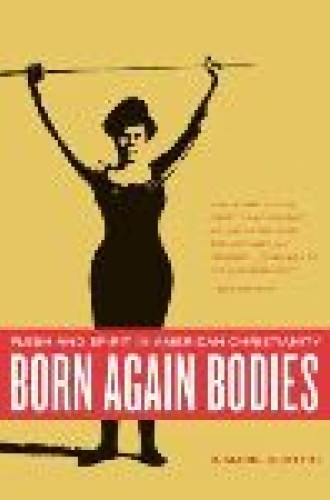

Born Again Bodies

If you are a Protestant and you are on a diet, you may not want to read this book. Although R. Marie Griffith examines the American Protestant understanding of the relation between body and spirit with vivid detail and skillful sensitivity to the complexity of the issues involved, after seeing the book’s pictures and reading its descriptions of the multitude of Christian diet movements of the past two centuries, you may never be able to diet in the same way again.

Griffith’s ultimate goal is to trace the history of Christian dieting movements (with names like the Weigh Down Workshop and Overeaters Victorious) that have had significant influence, particularly in evangelical circles. A professor at Princeton University and author of God’s Daughters: Evangelical Women and the Power of Submission, Griffith argues that these movements have their roots in phrenology, eugenics and the spiritualist movements of the 19th century. They promote the idea that the ideal human body is a slim white one and hint that other bodies are less loved by God and less likely to be saved.

Griffith begins her narrative with a brief and general history of understandings of the body in the Christian tradition, noting the ambivalence toward the body: it is both a vehicle for and an inhibitor of salvation. But her real story commences with the rise of consumer culture and the growing ties between consumerism, religion and control of the body. Grouped under the heading “New Thought” are a number of late-19th- and early-20th-century spiritual health gurus, including both the familiar founder of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, and others who have not exactly become household names, such as Gilman Low and Alice Long. Many of these leaders advocated fasting as a means to both spiritual and physical health, and some even went so far as to argue that over time the body could reach perfection and would no longer require food, being able to live on air alone.

The next section of the book leaves behind the New Thought spiritualists and continues on to Christian dieting books and movements, beginning with Deborah Pierce’s 1960 volume I Prayed Myself Slim. Griffith argues that what ties these two movements together is a white, middle-class obsession with the perfectible body and an insistence that such bodies are more inclined to divine favor. The dieting books that became a significant part of the Christian, and eventually evangelical, publishing industry during the 1980s and ’90s were written in styles that evolved from a confessional mode, with the requisite before and after photos, to an expert mode, with specific health and diet advice and biblical and devotional materials designed to increase motivation.

Both evangelical diet writers and evangelical dieters frequently emphasize that a slimmer body makes them more attractive not only to God but also to non-Christians; dieting, they argue, improves their Christian witness and makes them more likely to win converts. With this as justification, evangelical dieting movements have expanded with little protest or even acknowledgment from theological quarters. By defining a particular religious and devotional justification for dieting, these movements have created a niche market and have neatly and without contradiction tied their interests to the demands of consumer culture.

Griffith takes on the difficult task of including ethnographic material. She offers quotations from dieters whom she interviewed and some analysis of these interviews. But because of the book’s historical and textual emphasis, these few excerpts remain marginal. The interviewees accent her analysis, but don’t challenge or deepen it. This may be because, as Griffith acknowledges in her introduction, her own understanding of what Christian dieting movements mean departs severely from the understanding of those she interviewed. Her growing belief that dieting movements signal both misogynistic and racist tendencies in American culture cannot be reconciled with dieters’ belief that they are acting with God’s blessing as they develop slimmer and more disciplined bodies.

Griffith hopes that historical awareness of where the desire for a “born again body” comes from and how it has previously manifested itself can act as an antidote to the discourse on race, class and gender that is deeply intertwined with the desire for thinness and the link between thinness and faith. She asks readers not to disdainfully distance themselves from the images and descriptions she offers, but instead to recognize themselves in the cultural and historical formulations that make a born-again body the object of such intense desire. Griffith provides no easy answers, but she does offer the most complex and comprehensive view of these historical trajectories to date.