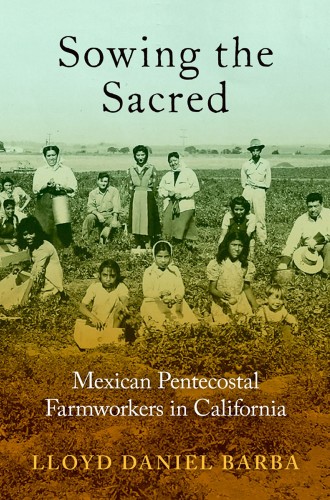

Pentecostals laboring in the field

Lloyd Barba shows how Mexican farmworkers established a viable life in the face of California’s industrial agriculture machine.

“The book is dedicated to the farmworkers who have broken their bodies, atoning for the nation’s sin of starvation.” So begins Lloyd Barba’s learned, perceptive, and hauntingly beautiful study of the miners, railroad workers, and crop pickers who toiled in California’s agricultural valleys between 1910 and 1960.

On the surface, the book’s subject is the origin and early history of the Apostolic Assembly of the Faith in Christ Jesus. This Pentecostal sect, gathered in the first decade of the 20th century and formally organized in 1930, was centered in the southwestern United States and northern Mexico. It now numbers more than 300 churches in California and nearly 800 nationwide. Until recently, most members spoke only Spanish.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Like almost all Pentecostal groups, the AAFCJ affirms the gifts of the Holy Spirit, strict rules about lifestyle, and exuberant worship enriched by stringed instruments and vigorous hand clapping. Divine healing is part of the package too. Barba tells of an Apostolic laborer who, when asked to name his family doctor, answered, “Jesus.” Unlike most Pentecostal groups, however, the AAFCJ is ardently Oneness in theology. A sect of a sect, it holds that God is not triune but one, manifesting the divine persons in three modes as Creator, Redeemer, and Sustainer.

“One’s heterodoxy is another’s orthodoxy,” Barba quips. To outsiders, this debate about the inner nature of the Godhead might seem a distinction without much of a difference, at least at the practical level. But to insiders, it is a life-and-death matter, splitting families and churches down the middle. The controversy drove Oneness partisans to the far edge of respectability on the American religious landscape.

Beneath the surface, Sowing the Sacred is a richly textured study of the daily lives of the Apostolics who packed the AAFCJ’s tents (and later, adobe mission-style tabernacles). Barba shows how they established a viable life for themselves in the face of an industrial agriculture machine that exercised iron control over the economy and social structures of California agriculture.

The exploitation ran so deep and proved so intractable that it defies simple description. For most believers, it entailed backbreaking toil, giving rise to the epithet “stoop labor.” Starvation wages, no benefits, and the necessity of uprooting their families and following the crops wherever and whenever they were ready for picking gave rise to another epithet: “vagrant.”

Juan Crow laws dictated “social discrimination, religious marginalization, and hard physical labor.” Barba tells it without flinching. “‘No Ni***rs, Mexicans, or dogs,’” ran the signs. Apostolics faced “dehumanization, biological reductionism, delousing, DDT fumigation, pesticide exposure while out at work, wage exploitation, relegation to the status of replaceable laborers, squalid housing, polluted water, denial of cultural and legal citizenship, and deportation along with its constant threats.” The lettuce and cantaloupes that graced White people’s tables came at a price.

How did Apostolics survive? By fashioning their experience into a sustained counternarrative, a stubborn refusal to let the growers’ master narrative represent them. Simply put, they survived by fighting back, in their own muted but defiant ways. While they harbored many forms of what political scientist James Scott calls “hidden transcripts,” Sowing the Sacred focuses on their religious experience at the site where the supernatural intersects with the mundane. To do water baptisms, for instance, Barba recounts how they turned “the most profane of places”—ditches, canals, fetid ponds, low-running muddy waters replete with pesticides—“into sacred space.”

Barba pioneers new ground with his granular depictions of women’s work. Women baked the prized tamales that were sold to fill the coffers that built the buildings, sewed the doilies that adorned the altars, maintained the movement’s boundaries with strict holiness dress codes, and nurtured the sinews of fellowship with their chatter in the kitchens and bathrooms, all outside the “panoptic male gaze.” They never made it into the pulpit (and still haven’t), but they perennially filled the majority of seats in their meetings.

Given the relative paucity of printed and archival sources for the AAFCJ, Barba creatively turns to other and perhaps more revealing ones. Hymnals, for one, were passed from hand to hand and found loving preservation in partisans’ living rooms. But most conspicuous is Barba’s mining of what historian Simon Schama calls the “veins of myth and memory” by meticulous examination of the photographs partisans took of themselves. Who made the cut? Who didn’t? How did they arrange their hands and feet and bodies for the camera? More than any other medium, these photographs show how profane materials came to embody sacred meanings.

Barba never comes close to reducing Apostolics’ experiences to their settings, as if those experiences were artifacts of some deeper reality. Rather, he shows how religion worked in the midst of believers’ lives, filling them with song and laughter and ligaments of love binding brothers and sisters in the Lord.

Barba’s prose is lovely. The book is not beach reading, but for a volume that seamlessly blends so many distinct disciplines—religion, ethnicity, immigration, agriculture, and economic history—it is remarkably fluid. Moreover, Barba is blessed with an eagle eye for the choice quotation. For pages on end, I found myself utterly lost in the inner worlds of Apostolics’ aspirations.

Like all great books, this one leaves readers with questions. What about attrition? Who left, and why? Did they come back when the outside world proved disappointing? More importantly, Barba—who teaches religion at Amherst College—never plays his hand about his own relationship to the Oneness Pentecostal tradition. Is he an insider? Outsider? Both at once? Does it matter? I think it does, because point of view influences what’s included (or not) and shapes the nuances that lie between the lines.

Finally, is the historical-critical method, when applied to a group that attributes its origins to the Holy Spirit, inherently intrusive? Differently asked, would Barba’s subjects have recognized themselves in this portrait? Would talk of counternarratives and hidden transcripts have made sense to them as they spoke in tongues amid the rhythms of guitars and mandolins?

I don’t know, but I am reminded of Richard Bushman’s advice to historians. We will meet our subjects in heaven someday, and when we do, we will have to look them in the eye and account for how we portrayed them. I suspect that Barba will come away a lot less scathed than most historians (me included), and quite possibly not at all. Someone has said that historical data are human faces with the tears removed. Barba puts back the tears.