The gates of evangelicalism

Isaac Sharp traces the story of the groups that find themselves outside, pushed there by the conservative White men standing guard.

I could hear the piano playing and people singing—especially the majority-male voices that were louder and carried farther than the female ones. As a newly employed assistant professor of religion, I was at my first all-faculty retreat. I’d taken a chance on this evangelical university because it had a Quaker connection, and I hoped the egalitarian Quaker impulse would neutralize the patriarchal and sexist aspects that thread through evangelicalism. Eager to belong, I found a seat, picking up the song sheet as I began to sing.

And then my heart sank. The lyrics were laden with masculine language. The full force of 21st-century evangelicalism’s marginalizing deftness, a determination to keep people and ideas that challenge the status quo at arm’s length, landed squarely on my shoulders. It was a weight I carried not only through the refrain of “This is my father’s world” but indeed throughout my tenure there.

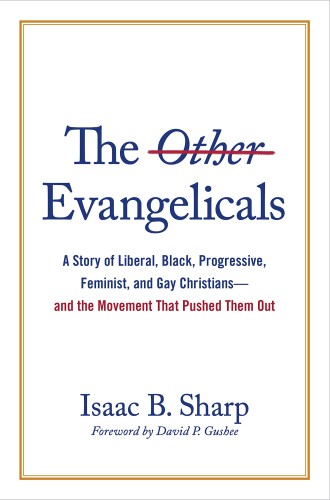

In hindsight, my experience at George Fox University is a microcosm of the astute analysis Isaac Sharp provides in The Other Evangelicals. Sharp, who currently teaches at Union Theological Seminary in New York City, provides a compelling story of evangelical gatekeepers—conservative White men who used (and continue to use) their power to restrict to the margins anyone who challenges their conservative White male identity.