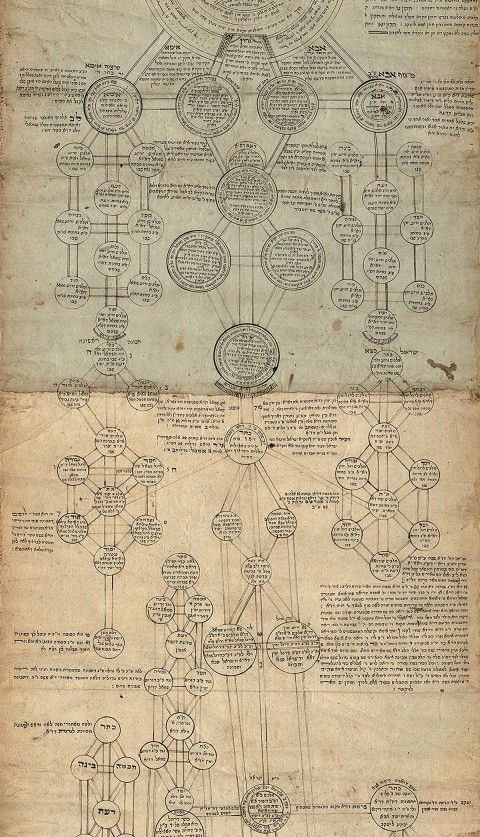

The tree of God’s mysteries

The Jewish Kabbalah tradition offers a way of understanding God in the world—one that has profoundly influenced Christianity.

The patriarch Abraham not only introduced monotheism but also proposed the concept of an invisible deity. Abraham’s God was beyond anything that the ancient world could imagine: this God could not be bribed nor inveigled to do something against God’s will. This God was both all powerful and totally humble. How, then, was an individual supposed to relate to God? How could humanity visualize the invisible?

The Jewish tradition had a further problem. One of the Ten Commandments forbids making a graven image. Though aimed mainly at the idolatrous practice of creating objects of worship, the commandment was taken more generally as a ban on any visual expression of the Divine. All suggestions of what constituted the Divine had to be verbalized, which is what the tradition of the oral law—or Torah shel b’al Peh, as opposed to the written law, Torah shel bichtav—does in spades.

Yet even this did not satisfy everyone, and in the 12th and 13th centuries, a new concept took hold in the Jewish rabbinical tradition: Kabbalah. The word literally means “receiving,” indicating that Kabbalah was an ongoing tradition received by the rabbinic elite, which in turn could share it with a select few acolytes. Kabbalah arose as an attempt to define the indefinable–the Ein Sof, the unending, or infinite, presence of God. God’s immanence could be intuited through sefirot. This Hebrew word contains a number of associations, including story, a thing written, a sapphire, and also sphere. In kabbalistic circles, these sefirot were graphically depicted as fruit hanging on a tree.