To forgive is exclusively divine

Ancient Israel’s war with Amalek is a lesson in repentance and covenant.

Source: Detail from Battle of Israel against the Amalekites by Abraham de Blois (Creative Commons)

In 1969, Jewish Holocaust survivor and Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal published a controversial book called The Sunflower, based on an experience he had as a young man in 1943 in the Janowska concentration camp in Poland. Wiesenthal had been assigned to forced labor in a converted army hospital, where he was instructed to clear medical waste. It was there that he encountered a wounded soldier named Karl, who flagged Wiesenthal down. Knowing that his wounds were likely fatal and that he would almost certainly die in the coming days, Karl begged Wiesenthal for a favor.

He had been an SS officer who had committed horrific acts of evil, and there was one act in particular that was causing him anguish, a crime so heinous that he was certain he would not merit entering paradise unless he received forgiveness from a Jew. The crime had taken place the previous year, when Karl and some other SS officers surrounded a Jewish apartment building, poured kerosene around it, and set it on fire. As Jewish men, women, and children leaped out of the windows trying to escape, Karl gunned them down. Three hundred people perished.

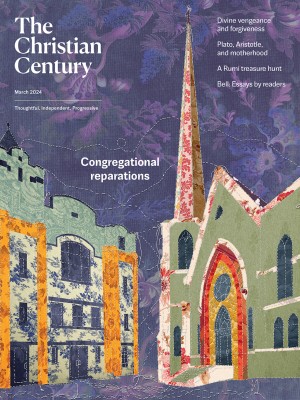

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Karl tearfully described his story to Wiesenthal and closed by begging him for absolution. He insisted that he was repentant but that he needed a Jew to forgive him before his soul departed for the next world.

Wiesenthal sat at Karl’s bedside, silently listening to his story. When Karl finally finished, Wiesenthal said nothing. After a few moments, he stood up, walked away from Karl’s bed, and exited the room. The next day, Wiesenthal returned to the army hospital and saw that Karl was not in his bed. He asked a nurse where Karl was, and she informed him that Karl had died the previous night. The question of whether Wiesenthal should have comforted the dying Nazi by granting him forgiveness rather than remaining silent haunted Wiesenthal for the rest of his life.

The first half of The Sunflower describes Wiesenthal’s encounter with Karl in detail; the second half poses this ethical question to ten scholars who weigh in on the topic in short essays. Some of them say that the right thing to do would have been to forgive, while others flatly refuse this possibility. Later editions of the book open the question up to more than 50 scholars, including Holocaust survivors, Christian clergy, and world leaders. The responses continue to be mixed.

I was looking at this book recently because my teenage daughter was assigned to read it in school. As I thumbed through the pages, I came across one response which I thought was especially striking, written by a Jewish writer known for his extraordinary compassion for all humankind. Rabbi, theologian, and Holocaust survivor Abraham Joshua Heschel insists that Wiesenthal was not permitted to forgive Karl because no human can forgive the moral wrongdoings committed by one person against another—only God can do that. This view was later corroborated by Elie Wiesel. “Who am I to forgive?” Wiesel said to an interviewer. “I am not God!”

Heschel and Wiesel were drawing from an idea that is deeply embedded in the Hebrew Bible: that forgiveness is an exclusively divine trait that the people of Israel require in order to survive. This theme is threaded throughout the Hebrew Bible, and it lies at the heart of the book of Leviticus. Leviticus opens with a series of theoretical scenarios in which members of the Israelite community, from communal leaders to common laypeople, err unknowingly. God provides these sinners with a mechanism by which to absolve themselves of their sins and encounter the presence of God.

The theme of divine forgiveness is a fitting starting point for Leviticus, which details the ritual practices and moral instructions pertaining to the administration of the tabernacles. These instructions address a tension that derives from the Israelites’ urge to draw close to God and the behaviors that disqualify them from doing so because they make the people ritually or morally impure. Leviticus 1–4 initiates the process of reconciling this tension by clarifying how the Israelites can be forgiven for their sins. It opens with a manual that lists the precise offerings that the Israelites should bring, depending on the nature of their sin:

The Lord summoned Moses and spoke to him from the tent of meeting, saying, speak to the people of Israel and say to them: “When any of you bring an offering of livestock to the Lord, you shall bring your offering from the herd or from the flock. If the offering is a burnt-offering from the herd, you shall offer a male without blemish; you shall bring it to the entrance of the tent of meeting, for acceptance in your behalf before the Lord. You shall lay your hand on the head of the burnt-offering, and it shall be acceptable in your behalf as atonement for you.” (Lev. 1:1–4)

The instructions described in this passage and what follows comprise a sort of handbook that guides the sinner through the process of atonement and exculpation. This process requires the sinner to recognize that God’s central characteristic is forgiveness—and that without God’s forgiveness, an encounter between God and Israel cannot take place.

The opening chapters of Leviticus are read in synagogues once a year on sabbath morning as part of the annual cycle of Torah reading. It’s at the same time of the year that Jews also recite Deuteronomy 25:17–19, which is tied to the holiday cycle and read each year on the sabbath prior to Purim, a holiday that usually falls in February or early March. This latter reading, known as the Portion of Remembrance, seems to ignore God’s desire for repentance and appears entirely uninterested in God’s inclination to forgive. In the Portion of Remembrance, God does not forgive.

Nor does God seem to want the people of Israel to forgive. Rather than telling the Israelites to remember to forgive Amalek, God instructs them to annihilate them:

Remember what Amalek did to you on your journey out of Egypt, how he attacked you on the way, when you were faint and weary, and struck down all who lagged behind you; he did not fear God. Therefore when the Lord your God has given you rest from all your enemies on every hand, in the land that the Lord your God is giving you as an inheritance to possess, you shall blot out the remembrance of Amalek from under heaven; do not forget. (Deut. 25:17–19)

How can we square God’s desire for repentance and reconciliation with God’s promise of eternal vengeance? If God by definition embodies moral perfection, then God must forgive those people who are repentant. In fact, besides the biblical passages regarding Amalek and his descendants, there is no instance in the Hebrew Bible in which God refuses to forgive.

Nor is there any example in the Hebrew Bible of true human forgiveness: it is a uniquely divine trait. For this reason, when Joseph’s brothers ask him for forgiveness after years of estrangement at the end of the book of Genesis, Joseph reminds them that only God has the capacity to forgive. As a quality only possessed by God, forgiveness must be extended to all those who repent.

What are we to make, then, of the contradiction between the presentation of God in Leviticus as a God of benevolent forgiveness and the presentation of God in Deuteronomy 25 as a God of justice and vengeance?

Because God by definition embodies moral perfection and therefore is self-obligated to forgive those who are repentant, God’s refusal to forgive Amalek must mean that Amalek refused to repent of its immoral attack against the defenseless Israelites. The story about Amalek’s attack, however, is about more than God’s refusal to forgive the unrepentant Amalekites. It is about how God’s treatment of Amalek is an empathetic act which reflects God’s desire that all people, and the Israelites in particular, repent of their sins through the restoration of their faith.

Amalek’s attack takes place after a series of complaints and misbehaviors on the part of the Israelites, who continuously express skepticism about the strange and unfamiliar God who redeemed them from slavery. The last of these misbehaviors takes place when the people stop to rest in the desert wilderness and cannot find water. Delirious with thirst, the people become panicked and beg Moses to take them back to Egypt. Desperate to quell the people’s incessant complaints and fearful for his life, Moses responds by turning to God, who instructs him to strike a rock with his staff. This action causes the rock to miraculously gush water, which satisfies the people.

The place where this incident occurred is named Masa uMerivah, which can be rendered as something like “trial and strife” on account of the argument that the Israelites made against God by asking whether God was truly in their midst: “He called the place Massah and Meribah, because the Israelites quarreled and tested the Lord, saying, ‘Is the Lord among us or not?’” (Exod. 17:7).

The story of Israel’s lack of faith at Masa uMerivah is a middle chapter in a much longer story about the Israelites failing to recognize the total dominion of God. The next chapter of this story is Amalek’s attack. It is clear from the outset that the only way for the Israelites to defeat Amalek is to rectify their sin of doubting God. This is why rabbinic traditions suggest that Moses’ raised hands, which lead to Israel’s military victory, are a sign of prayer that inspires the people to recognize God’s universal dominion. The people lack faith, and they need to acquire it, fast—before God presents them with the Torah and the covenant at Mount Sinai.

Moses’ raised hands also signify something more basic: that Moses is not directly involved in the battle. Unlike other tribal leaders in the ancient world, Moses did not come into his position by military might. Instead, he was chosen to serve as a mediating figure for the people’s true leader, their God. By showing that he holds no weapon except for a simple walking staff, Moses demonstrates that the people’s victory has nothing to do with his physical power and everything to do with their surrender to God. As a reminder that the Israelites’ survival depends on God, Moses’ raised hands act as reparation for the people’s lack of faith that they exhibited at Masa uMerivah, and they embody his attempt to garner divine forgiveness.

Reading the story of Amalek as a story about the Israelites’ attempt to attain forgiveness also explains why God instructs Moses to put the story into writing and memorialize it for perpetuity. The Israelites must forever remember their encounter with Amalek—not because it is so important that they annihilate an enemy, but because they must remember that God is in control of their survival. This concern is reflected in the name that God gives this battle:

Then the Lord said to Moses, “Write this as a reminder in a book and recite it in the hearing of Joshua: I will utterly blot out the remembrance of Amalek from under heaven.” And Moses built an altar and called it The Lord Is My Banner. He said, “A hand upon the banner of the Lord! The Lord will have war with Amalek from generation to generation.” (Exod. 17:14–16)

This is a war that God wages on behalf of those who recognize God, even as those very same people wage a battle (a riv in Hebrew) against God.

In the wake of Masa uMerivah, the people discover that God controls their destiny. And in the wake of the war against Amalek, the people learn that God protects them, even when they lack faith. This protection is an act of irrational love. God’s desire for revenge against a sinner who embodies moral evil, therefore, is not a reflection of excess rage. By definition, God simply cannot forgive Amalek, because Amalek has not repented. What is excessive is not God’s rage but God’s mercy toward the people whom God has chosen. This mercy motivates God to encourage Israel to draw closer to the divine Presence, even as they doubt God’s loyalty.

Read this way, the injunction to take vengeance upon Amalek in the book of Deuteronomy is consonant with the opening chapters of Leviticus. Both sections of the Torah present God as desiring human repentance. But because Israel participates in a unique covenantal relationship, God nudges Israel toward repentance even when the Israelites do not take the initiative to repent. The difference between Israel and Amalek lies not in the innate superiority of one community over the other but in the mysterious and incomprehensible selection of Israel over the other nations.

All nations, including Israel, have moral failings. But only the Israelites’ moral failings pain God so much that God jump-starts their repentance by fighting their wars and by giving them a tabernacle through which they can repent of their sins and encounter the Divine. Only the Israelites are gifted with a unique and special mechanism to bring them to repentance. The mystery at hand is not the question of why the Israelites are instructed to take vengeance upon Amalek, but why God chose the people of Israel for a covenantal relationship.

God’s desire for Israel’s repentance is also at the foreground of Amalek’s story in the book of Deuteronomy, when Moses repeats the injunction to wipe out the memory of Amalek to a new generation of Israelites in the 40th year of the desert. Whereas in the book of Exodus Amalek attacks just after the people lose faith at Masa uMerivah, Amalek is mentioned in the book of Deuteronomy just after a description of potential social conflicts that will arise after the people settle in the land of Israel. These conflicts are referred to as a riv, the same word at the heart of the name Masa uMerivah. In both passages, Amalek’s attack comes on the heels of incidents, whether in the past or in the theoretical future, that test the people’s faith and that highlight how their own impiety endangers their survival.

Moses, however, makes some perplexing changes to the story of Amalek. In Exodus, God defeats Amalek in order to encourage the Israelites to overcome their lack of faith and gain God’s forgiveness. The story’s central theme is that God alone controls Israel’s survival. But in Deuteronomy, Moses imagines a time when the people will bear the personal agency to independently perfect their society and their relationship to God. This accomplishment will negate the need for Amalek to ever attack. Exodus has God doing all the work of erasing Amalek. In Deuteronomy, Moses instructs the people themselves to “remember what Amalek did to you. . . . Do not forget” (25:17–19).

Moses insists that the people must associate Amalek’s attack with their personal failure to fear God. Most translators interpret the Hebrew phrase for “did not fear God” in this passage as a reference to Amalek. But the clause could also refer to Israel, the same Israel that asked whether God is in its midst in the book of Exodus before Amalek attacked. Forty years after the war with Amalek, Moses tells the people that they are now expected to take the project of their moral perfection, and their fear of heaven, into their own hands.

If the Israelites successfully achieve this, their lives will be so harmonious that a time will come when they will not remember what it was once like to have enemies who wanted to annihilate them. Read this way, the phrase “you shall blot out the remembrance of Amalek from under heaven” is not an injunction to annihilate but a blessing of comfort.

A close reading of Amalek’s attack suggests that this story is about God’s desire for the Israelites to repent so that God can forgive them. Rabbinic commentators on this story, however, struggled with the long-term nature of the injunction to be at eternal conflict with Amalek. It makes sense that God would not forgive the generation of Amalekites who attacked Israel and did not repent. But how could God promise to be at war with Amalek forever? Would not such permanence negate the possibility of Amalek’s repenting?

One solution suggested by the rabbis is that the possibility of repentance is always present. Amalek is only the enemy of Israel as long as it decides to be. Amalek always has the potential to abandon its immoral nature through repentance: Amalekites, according to some rabbinic sources, can even convert to Judaism. According to one passage preserved in the Babylonian Talmud, not only did descendants of Amalek convert to Judaism but their descendants studied Torah among the greatest rabbis in the city of Bnei Brak:

The Gemara adds that some of Haman’s descendants studied Torah in Bnei Brak, and some of Sisera’s descendants taught children Torah in Jerusalem, and some of Sennacherib’s descendants taught Torah in public. Who are they? They are Shemaya and Avtalyon, the teachers of Hillel the Elder.

(b. Gittin 57b)

This same idea finds earlier expression in the book of Esther, when Persians who had supported Haman the Amalekite’s project to wipe out the Jews convert to Judaism. Esther contains the only reference in the entire Tanakh to such converts, whose repentance led to their incorporation into the nation of Israel:

In every province and in every city, wherever the king’s command and his edict came, there was gladness and joy among the Jews, a festival and a holiday. Furthermore, many of the peoples of the country professed to be Jews, because the fear of the Jews had fallen upon them. (Esther 8:17)

The Persians in this passage convert out of fear of the Jews—rather than out of fear of God, the very kind of fear the Israelites themselves lack in Exodus and Deuteronomy. Nevertheless, the Persians’ conversion is regarded in rabbinic memory as ultimately sincere.

If the Amalekites and their supporters can repent so completely that they transform, convert, and assimilate into the Jewish nation, then the story of Amalek in the books of Exodus and Deuteronomy cannot be read as a story of divine ruthlessness or as a story about God’s desire to enact genocidal vengeance against the nation of Amalek. The story is not about biological identity at all. Just as any individual can choose to engage in moral or immoral behavior, any nation can don or doff the characteristics of Amalek.

The story of Amalek is about God’s desire for Israel to repent so that God may forgive them and nurture a relationship with them. It is a story that reminds us that God forgives all those who repent of moral evil. But because God has chosen Israel for a special relationship, God nudges Israel toward repentance. As Heschel and Wiesel once noted, the Jewish people cannot forgive unrepentant moral evil because forgiveness is not a human trait. But they can, like all people, remember their obligation to strive for moral perfection. Acting upon this obligation is an affirmation that God engages in the human realm, continuously longs for Israel, and, for mysterious and incomprehensible reasons, invites a covenantal people to participate in a transcendent relationship that can mobilize the world toward moral perfection.