An anti-Christian lawsuit

When Texas attorney general Ken Paxton filed a suit against a Catholic volunteer organization in El Paso, he went against his own church’s statement of faith.

Hospitality as an exercise of Christian faith is not groundbreaking theology. The hospitality of early Christian communities was so great it earned them the ire of the Roman government. “These impious Galileans not only feed their own poor, but ours also,” wrote emperor Julian the Apostate. “While the pagan priests neglect the poor, the hated Galileans devote themselves to works of charity.” A century later, Saint Benedict insisted to his fellow monks that every guest who arrived on their doorstep “be received as Christ.” More recently, Black Christians in the US hosted escaped enslaved people in their homes as part of the Underground Railroad, and European Christians such as Corrie ten Boom found themselves sent to Nazi concentration camps for harboring Jews in their homes.

Liberation theologians like Gustavo Gutiérrez may have given the practice of Christian hospitality new names or new contexts, but it is not novel in any way. The tradition of Christianity is a tradition of hospitality, one that has flourished alongside, and often despite, a second, equally historic pattern: one of vitriolic, sometimes violent government opposition.

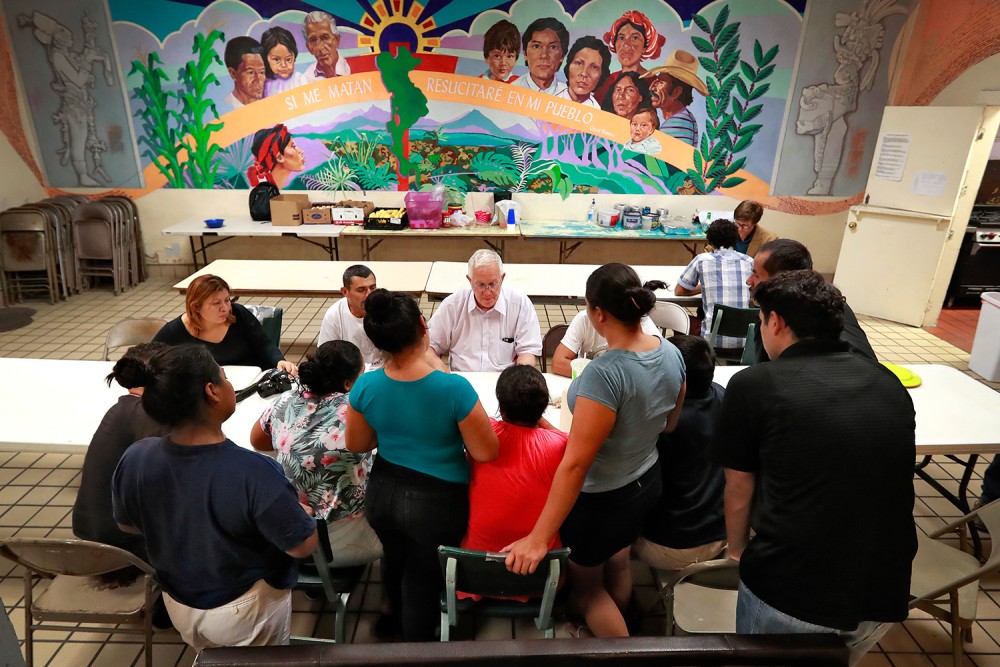

In February, Texas attorney general Ken Paxton announced a lawsuit against Annunciation House, a Catholic organization in El Paso that seeks to “accompany the migrant, refugee, and economically vulnerable peoples of the border region.” The organization runs multiple shelters, staffed almost entirely by volunteers, where migrants are given food, a place to sleep, and a change of clothes. Paxton’s suit claims that Annunciation House is facilitating “astonishing horrors” including human smuggling, lawlessness, and the maintenance of stash houses. (Last week, a state district judge blocked Paxton’s investigation for the time being.)