End times for end times

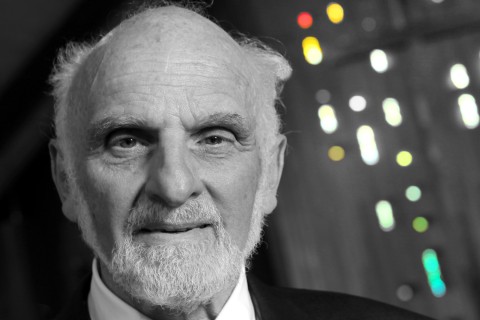

Franklin Graham, son of the famous evangelist, recently warned that the rise of Ebola signaled that we are living in the last days. Few people noticed. Christian filmmaker Paul Lalonde released an awful movie in October about the end of the world. Despite snagging Nicolas Cage for the lead role, Lalonde’s retooling of Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins’s bestselling Left Behind books fell flat with audiences. Meanwhile, megastar preachers Rick Warren, Joel Osteen, and T. D. Jakes all downplay the strident eschatology that characterized the churches of their youth.

Evangelical apocalypticism looks almost dead.

This was not always the case. As modern evangelicals’ grandparents and great-grandparents gave birth to fundamentalism and then its successor neo-evangelicalism, nothing animated their lives or their theology more than the conviction that Jesus was coming. And nothing distinguished them more from their liberal Protestant counterparts than the belief that the earth was beyond redemption.

Fundamentalists believed that the world was careening rapidly towards a series of cataclysmic events described in biblical prophecy. They taught that the Holy Spirit would soon turn this world over to the Antichrist, a diabolical world leader who would preside over an awful holocaust in which those true believers who had not already been raptured to heaven would suffer interminable tribulations.

But just when all hope would seem lost for those still on earth, fundamentalists preached that Jesus would return with an army of saints to defeat the Antichrist at the literal Battle of Armageddon. His victory would pave the way for God to establish a millennium of peace and prosperity, a new heavens and a new earth.

In crafting this argument they adapted traditional premillennial theology and fit it to their time and place. Fundamentalists and evangelicals saw in each of the major global events of the 20th century proof that the time is nigh. World War I, women’s suffrage, the Great Depression, World War II, atomic bombs, the creation of the United Nations, the “lawlessness” of the civil rights movement, and a 1970s oil crisis all seemed to be incontrovertible evidence of the looming tribulation.

Then came the rise of the religious right and the presidencies of Ronald Reagan and especially George W. Bush. Evangelicals, no longer prophets and dissidents, were welcomed into the highest echelons of power.

As their influence and power skyrocketed in the 21st century, the faithful have invested more and more time in working towards achieving the kingdom of God in this world rather than in preparing humanity for the next.

Most evangelicals no longer draw elaborate maps seeking to identify Gog and Magog, or look for evidence of the rebirth of the Roman Empire, or wonder when animal sacrifices will commence again in Jerusalem.

Evangelicals, and evangelicalism, have become respectable. Charles Colson made this clear immediately after 9/11. Rejecting prophetic prognostication, he counseled readers of Christianity Today: “I try to avoid end-times prophecy that makes Christians appear irrelevant to the world.”

Polls, however, tell a different story. A 2010 Pew Research Center study revealed that 41 percent of all Americans (well over 100 million people) and 58 percent of white evangelicals believe that Jesus is “definitely” or “probably” going to return by 2050. According to the 2014 Bible in American Life report, of the 50 percent of all Americans who had read the Bible at all in the previous year, over one-third claimed that they did so “to learn about the future.”

Evangelicals no longer have to obsess over an imminent rapture and the premillennial second coming of Christ. They have been so successful in equating their particular beliefs with the Christian faith writ large that premillennialism is now taken for granted. Ideas that originated among a small fringe of radicals 150 years ago are now assumed to be the faith, once and for all delivered to the saints.

So while Lalonde and Graham seem out of touch, and they embarrass many evangelicals, it is for one reason alone: they are fighting a battle that has already been won. Americans, well-versed in rapture theology and facing an environmental crisis, global warming, a new pandemic, and weapons of mass destruction, already know—the end is near.

Our weekly feature Then and Now harnesses the expertise of American religious historians who care about the cities of God and the cities of humans. It's published in partnership with the Kripke Center of Creighton University and edited by Edward J. Blum and Kate Bowler.