Preach it like Lincoln

Today is the 150th anniversary of the Gettysburg Address. To mark the occasion, the Abraham Lincoln Historical Library asked a number of luminaries—presidents, poets, sailors aboard the USS Lincoln—to offer their thoughts about the historic speech. But there was a catch: they had to limit their remarks to just 272 words, the length of Lincoln's address. NPR's Scott Simon concluded his essay (essayette?) with these words:

Lincoln's words remind us at once of the brevity of life and the imperishability of humanity. The clock ticks, the calendar flips. No power exists to slow them down or manufacture more hours and years. Abe Lincoln reminds us to make our own lives count by filling the hours we have with what's worthy, kind, funny and honorable.

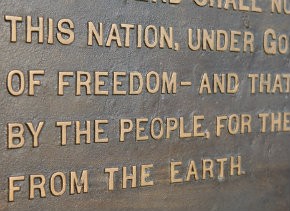

In a grade-school civics class long ago, I was required to commit Lincoln's words to memory. I made it through, no thanks to "the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced." Now that I’m a pastor, I recognize in Lincoln's words the classic preacher's conundrum: the call to put words around that which is ineffable. At Gettysburg, Lincoln acknowledged the limitations of language—even as he gamely offered words that continue to inspire us seven score and ten years later.