How executive orders work and why they don’t always last

President Joe Biden arrived at the White House ready to wield his pen to dismantle Donald Trump’s legacy and begin pushing his own priorities.

Presidents Trump and Barack Obama both relied on executive orders and other presidential directives to get some of their most controversial policies around a deadlocked Congress. But no president has come out of the gate as eager to use the authority as Biden.

An executive order is a written, signed, and published directive from the president that manages operations of the federal government.

Congress can’t just pass legislation to overturn an order, but it can use legislative action—such as cutting off funding—to gum up the president’s intentions. A new president may overturn a predecessor’s order by issuing another executive order effectively canceling it. Biden did that repeatedly during his first days in office as he looked to chip away at Trump policies over a gamut of issues, including environmental regulations, immigration policies, and the government response to the coronavirus pandemic.

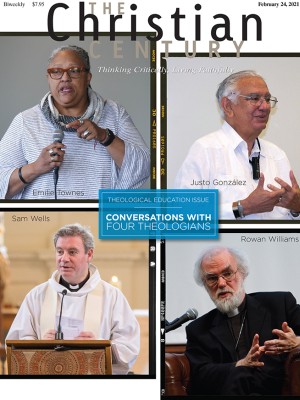

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Many executive orders are innocuous, such as giving federal employees the day after Christmas off. But executive orders can also be used by a president to push policy objectives that the leader can’t get through Congress.

Many of Biden’s orders during his first days in office were directly related to the pandemic—a mask mandate on federal property, an executive order providing guidance on safely reopening schools, and stopgaps intended to increase food aid and protect job seekers on unemployment because of the virus.

But Biden has also used executive action to try to wind the clock back more than four years to the Obama presidency.

For example, Biden signed a memorandum to preserve Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, the Obama-era program that has shielded hundreds of thousands of people who came to the US illegally as children from deportation since it was created in 2012 through an Obama directive. Trump took steps to undo DACA in 2017.

Other orders targeting foundational policies of the last administration include a Biden directive to reverse Trump’s ban on travelers from several predominantly Muslim countries, executive action to rejoin the Paris climate accord, and a proclamation stopping construction of his predecessor’s border wall.

To be sure, modern presidents from both parties have been heavy users of executive orders—and have been criticized by the opposition party. Bill Clinton had 364 orders over two terms, George W. Bush signed 291, and Obama issued 276. Trump in his one term signed 220 orders.

Both Congress and the courts can check a president’s power to govern by executive fiat.

Already, Biden saw his attempt to order a 100-day deportation moratorium hamstrung by a federal judge. US district judge Drew Tipton found the Biden administration had failed “to provide any concrete, reasonable justification” for a pause in deportations and ordered a restraining order blocking Biden’s order from going into effect.

The experiences of both Trump and Obama underscore the fleeting nature of executive orders. Both saw their most durable policy legacies come through congressional legislation—for Trump, the 2017 tax cuts, and for Obama, his signature Affordable Care Act.

Trump tried mightily but failed to push a Republican-controlled Congress to repeal “Obamacare.” He did, however, diminish a key aspect of the health-care law when his own tax overhaul legislation reduced the penalty for not having insurance to $0.

Now Trump is seeing many of his own orders, proclamations, and memoranda shredded by Biden. And Biden could very well see many of his executive actions undone by whoever follows him into office.

Biden economic adviser Brian Deese acknowledged that some of the president’s executive actions—such as directives retooling government calculations on food assistance for Americans living in poverty and another extending moratoriums on evictions for Americans whose lives have been upended by the pandemic—were merely stopgaps as the president tries to win bipartisan support for a $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief package.

In the end, Deese said, the orders, while helpful, are pale substitutes for comprehensive legislative action passed by Congress. —Associated Press