An old man dreaming dreams of psalms

Paul Simon isn’t religious, but the voice he heard in his sleep seems to be.

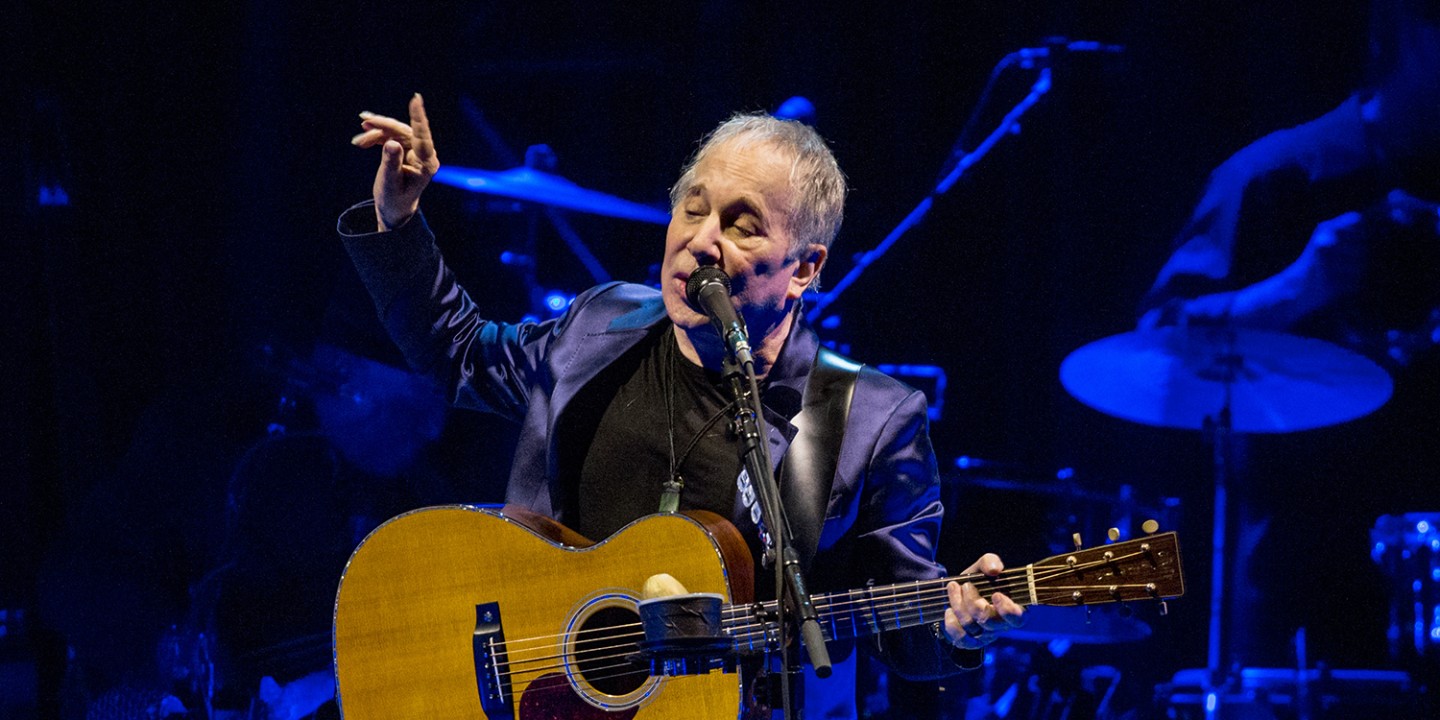

Singer-songwriter Paul Simon performs at Royal Albert Hall in London. (Photo © Rob Ball / WireImage)

As a young man, at age 26, Paul Simon shared a vision of what it would be like to be old in his song “Old Friends” (with Art Garfunkel): “Can you imagine us / Years from today / Sharing a park bench quietly? / How terribly strange / To be seventy.”

Not all visions from youth come true, of course. When Simon was 70, he was not sitting on a park bench quietly. Far from it. He was touring the world, performing songs he had written over a remarkable career spanning over five decades. There was a lot of material to draw from. In addition to his collaborations with Garfunkel, Simon has released 15 solo albums. He has also been awarded 16 Grammys for his work.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Now, at age 81, Simon is an old man dreaming dreams—quite literally—and turning those dreams into art of the highest order.

On January 15, 2019, as he tells the story, Simon had a dream in which he heard a voice saying, “You’re working on a piece called Seven Psalms.” The dream was vivid, but he didn’t know what to make of it. In an interview with CBS’s Anthony Mason, Simon reflected on the experience: “Since it came to me in a dream with someone or something’s telling me to do this, I said, well, look, it’s not my idea anyway, so I’ll just wait ’til there’s clarification of what I’m supposed to do.”

Over time, some clarification came. Simon would wake up two or three times a week, between 3:30 and 5 a.m., and start writing the words that came to him. Teachers of writing have often advised taking advantage of the liminal time between sleeping and waking, dreaming and consciousness, which can foster extraordinary creativity. When writing his earlier songs, Simon had occasionally felt inspired to write by a source somehow outside of himself. This was something different, however. The process was laced with mystery, as if the words were given to him and his role was to be no more—and no less—than a scribe. At a time when his contemporaries were traversing the globe on farewell tours and indulging our voracious appetite for nostalgia, Simon was alone in the night dreaming, listening, and writing.

The result is Seven Psalms, a piece that is 33 minutes long, consisting of seven sections (“psalms”) in one long track, intended to be listened to in one sitting and thus experienced as a whole.

The first words Simon sings are, “I’ve been thinking about the great migration / Noon and night they leave the flock,” which would seem to signal that the work that follows is going to be a reflection on mortality. Simon refutes this interpretation with vehemence, perhaps because he doesn’t want to have this piece viewed as another farewell tour de force like those some of his contemporaries have produced. David Bowie’s Blackstar and Leonard Cohen’s You Want It Darker, powerful confrontations with mortality by artists in full command of their powers, were recorded when each artist knew his death was imminent. That is not the case with Simon.

Often artists are reluctant to interpret their own work. There’s a story of Robert Frost being asked to interpret one of his poems and responding, “What do you want me to do? Say it again in worse English?” Although Simon also declines to interpret his work in any detail, in this instance he does seem intent on sending us in the right direction. He summarizes his intention in the album’s YouTube trailer: “This whole piece is really an argument I’m having with myself about belief, or not.”

This does not mean, however, that Seven Psalms is a religious work in any conventional sense. In an interview with Simon for the CBC, Tom Power begins to broach the subject by saying, “I don’t know your religious inclination—” Simon abruptly interrupts him: “I have none. . . . I am not religious.” Simon was born to Jewish parents and had a bar mitzvah at a synagogue in Queens, New York, but that was the end of his formal religious engagement.

To be sure, there are traces of religious influence in some of his earlier work. “Loves Me like a Rock” has the feel, and even some of the vocabulary, of a gospel song. “Bridge over Troubled Water” would not seem out of place in a volume of contemporary hymns.

More explicit references to religious themes, however, rarely appear in Simon’s work. When they do, the tone is most often sardonic (“Coo, coo, ca-choo, Mrs. Robinson / Jesus loves you more than you will know”). One of Simon’s songs, “The Afterlife,” depicts a journey to heaven that is as burdened with bureaucracy as is a trip to the DMV. Everyone, including the Buddha and Moses, spends their time waiting in line and filling out forms. “The Afterlife” is clever and even a bit catchy, but it is no more a serious reflection on things eternal than Joni Mitchell’s “A Case of You” is a paean to the glories of beverage retail.

Then comes Seven Psalms. It is drenched—no, immersed—in religious imagery. Simon may not be religious, but the voice he heard in the night decidedly is.

The first sounds one hears in the piece are chimes and gongs, redolent of sacred rituals in a variety of traditions. Next comes the gentle pluck on the strings of a solo guitar (in fact, the Hebrew word for psalm derives from the root “to pluck”). The guitar is then joined by Simon’s singing. His voice is thin, almost hesitant, like the sound of a fragile reed in an uneven breeze. To me, the timbre of his voice only adds to the poignancy of what he is singing. This is not an artist boldly demanding the attention of an audience; it is a human being who has been hushed into something like reverence.

Before we know it, Simon is leading us into a sea of metaphors for God:

The Lord is my engineer

The Lord is the earth I ride on

The Lord is the face in the atmosphere

The path I slip and I slide on

...................

The Lord is a virgin forest

The Lord is a forest ranger

The Lord is a meal for the poorest of the poor

A welcome door to the stranger

It soon becomes clear why Simon wants us to listen to the piece as a whole. This is not hymnody, and certainly not popular song. The music and accompanying lyrics wash over the listener and eventually become an immersive experience. And that takes time.

The lyrics also are not meant to be exegeted as one would a sacred text. We would search in vain for anything like the elements of a creed in his words. Rather, this is a kind of guided meditation, impressionistic and evocative.

Much of this piece is in the same meditative tone. The one exception is the psalm called “My Professional Opinion.” Its lyrics are playful and its music a pastiche of Delta blues. (Simon has always been a gifted mockingbird, able to imitate the musical styles of others.) I do not find this break from the mood of the rest of the piece jarring. Rather, it seems like a knowing wink from Simon, signaling that we are meant to take this journey seriously but that does not mean we have to be dour about it.

I found the last psalm, “Wait,” particularly affecting. Simon is joined by his wife, Edie Brickell, for what is, in spite of his protestations about the work as a whole, a reflection on mortality. That is fitting. After all, how can one reflect on the possible existence of God without eventually confronting the reality of death? (The reverse also is true.)

In the beginning of “Wait,” Simon seems barely able to muster a plaintive plea:

Wait

I’m not ready

I’m just packing my gear

Wait

My hand’s steady

My mind is still clear

Brickell, as if gently taking his hand, responds with an assurance that is reprised at the end of the piece:

Life is a meteor

Let your eyes roam

Heaven is beautiful

It’s almost like home

Children! get ready

It’s time to come home

Then, at the very close, with soft chimes and gongs that seem to beckon from a distance, the two join in singing a simple “Amen.”

Each time I have listened to Seven Psalms, after the “Amen” is offered, I have sat in silence for a time—not because I chose to, but because I have felt compelled to. This is not a young man’s sound of silence. It is something more.

Here is a poignant postscript: while working on the album, Simon began to lose hearing in his left ear. By the time he completed his work, he had only 8 percent capacity in that ear. This explains why his singing on the album occasionally turns slightly flat and why he does not plan to perform Seven Psalms in concert or to tour in the future.

The Bible is filled with examples of people who are in some way disabled by revelation. Jacob walks with a limp after wrestling with an angel. Zechariah loses the power of speech after hearing the angel’s announcement that his elderly wife, Elizabeth, is to give birth. Saul loses his sight for a time after encountering the risen Christ on the road to Damascus. It seems that revelation, powerful encounters with God, can come at a cost.

For Simon to eschew playing his hits, to leave behind his gold records in his golden years, to venture forth into uncharted territory, and to dare to bring us along, is nothing short of valorous. The artist Henri Matisse was right: “Another word for creativity is courage.”