What we lost when the funeral home replaced the home funeral

Death rituals used to happen in our houses. What if we brought them back?

I frequently walk the alley across from our house to a coffee shop on Main Street in our quaint, small, midwestern town. Like most alleys, it is lined with forgotten or hidden things. Neighbors park their vehicular eyesores at the back of their property so that no one but alley walkers can see them. Flowers on bushes that were planted as fences suddenly bloom like a beautiful secret.

A few paces farther, a large but tidy house sits at the crest of the alley, facing Main Street. It is old but well maintained and neatly refinished with cream-colored siding and dark red shutters.

Only from the alley can you see a curious feature that separates this house from the others that line the path: a round metal tube extends toward the sky, too large to be a normal chimney. It pumps smoke into the air all year round, even on warm summer days.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

From the back of the house, this is the only evidence that bodies are being burned inside.

Like many funeral homes, this place of business has been made to look like an actual home, both inside and out. Designed for ease and comfort, funeral homes are often decorated with overstuffed comfy chairs, carpets in soothing colors, patterned wallpaper just a few decades out of date. Soft music plays; low, measured murmurs drift unobtrusively through the rooms. A chapel-like room is used for services.

But what would we see if we went farther into the bowels of the funeral home, into the basement or the outbuildings behind the house? Hidden things: places to store corpses, the tools of embalming, a crematorium.

We might witness what mortician Caitlin Doughty describes seeing while working in a crematorium in San Francisco in her darkly funny memoir, Smoke Gets in Your Eyes. Nothing prepares you, she writes, “no matter how many heavy-metal album covers you’ve seen, how many Hieronymus Bosch prints of the tortures of Hell, or even the scene in Indiana Jones where the Nazi’s face melts off,” for what it looks like to see a “flaming human skull” burning in an oven.

Or perhaps we would see an embalming in process: all of the blood in the entire body drained and replaced with embalming fluids that brighten and preserve the skin. We might see the mouth sewn, glued, or clamped shut so as not to disturb mourners, the eyelids glued together, and much of the contents of the body cavity sucked out through a tube inserted into the abdomen. “Embalming restores a lifelike appearance to the deceased,” writes Mark Harris in Grave Matters. “Refrigeration does not, which may only matter if you expect the dead to resemble the living.”

Making things resemble the things they once were or the things that they are not is one special task of funeral directors. It is no wonder funeral homes look as they do on the outside and beckon mourners with the word home. Would anyone in our death-averse culture be willing to enter if it looked on the outside the way it does in the places where the dead are prepared for the eyes of the living?

My own house has doors built for death. Constructed in the 1850s, it has narrow stairways that appear in unexpected places (and are perfect for hide-and-seek), with steps that creak and bend from more than a century of foot traffic.

It wasn’t long after we moved into this old house that I began to wonder about our front doors—of which there are three. We started finding packages delivered to each door. Knocks rattled across the house so that I wasn’t sure which of the three doors a visitor had decided to try.

“What a strange thing, to have three doors,” I said to one guest who’d grown up in the area.

“Oh,” he said, “they’re built for wakes. You know, to keep the line of people moving, from one door to the other.”

This information shook me. I could suddenly imagine the bodies of those who had lived in our house laid out in our dining room. The elderly, widowed spouse mourning a husband who died from heart disease or a wife who died in her sleep. Or worse heartaches too painful to imagine as I watched my four children play hide-and-seek in the house’s nooks and crannies.

At the time my house was built, people often died at home rather than in hospitals. Their families cared for the bodies. Typically, the deceased was washed and groomed by the women of the household and clothed in a simple home-sewn garment or winding-sheet, a cloth that, when wrapped around a body, made the dead resemble a mummy. Sometimes people would sew their own death shrouds.

These death rituals were carried out in community—a group of people with a history, with communal memories and rituals, who shared ways to grieve and manage the reality of death.

Today, the home has lost its place at the center of our death rituals. We no longer live near our families of origin, and our communities do not function in the ways they once did.

Death practices in the United States had changed greatly by the 1940s, when Howard Thurman gave his Ingersoll Lecture at Harvard. Thurman said that as death moved out of the home and into the hospital and the mortuary, “our primary relationship with death [became] impersonal and detached.”

In her early years as a mortician, Doughty saw the strangeness of this cultural decision to hand over death rituals to the professionals. On her first day at the crematorium, she was expected to shave a dead man’s body. A 23-year-old who had never seen this man before and knew very little of dead bodies was tasked with caring for his body instead of his family or community.

Poet and funeral director Thomas Lynch writes in The Undertaking that we often try to prearrange things like funerals in order to “pre-feel the feelings” that accompany death. Perhaps the cultural release of the distasteful parts of death to the care of others is done in an effort to un-feel, to move on from grief more quickly, to get back to life instead of dwelling on death.

But this displacement of our grief onto the funeral industry has consequences. When we are so far removed from death, the result is a strain on our emotional lives. According to Thurman, “tremendous emotional blocks are set up without release, making for devious forms of inner chaos, which cause us to limp through the years with our griefs unassuaged.”

It’s no wonder that some of our best writers and teachers on death, like Doughty and Lynch, have practiced death many times over. They have handled the most gruesome parts of death and have returned as witnesses to some of the deepest truths of the human experience.

The funeral industry’s death practitioners provide invaluable services, and many of them are family businesses that serve small communities like mine. But there was a time when more of us lived in closer proximity with death and leaned more readily into its mysteries. Lynch embalmed his own father, a process he describes with beauty and heartbreak. It helped him and his siblings to grieve.

When death came to our homes in previous generations, it mingled where family meals were shared, stories were told, and babies were born. In the place where dead bodies were laid out, life had been lived.

Death was never meant to leave our houses.

Harris tells the story of Beth, a woman who had to face the unimaginable death of her child. Beth made an unusual decision, at least in our culture. Instead of releasing the body to the funeral home or mortuary for storage, cleaning, or embalming, Beth decided to care for her six-year-old daughter’s body herself. She said it helped her accept the reality of her death.

Afterward, Beth became a “death-care midwife,” teaching people across the country how to prepare their loved ones’ bodies for burial. According to Beth, the natural condition of the body after a three-day wake helps the bereaved let go: “The body is often beautiful that first day . . . by the third day, the deceased begins to look like an empty shell.”

One evening my husband told me that if he died first, he didn’t want me to send his body to the morgue to be kept or to the funeral home to be prepared. He pointed to our dining table in our creaky old house. He wanted his body to be laid out there like many others before him, opening two of our three doors for mourners to file in and out.

Am I really prepared to give my husband a home funeral? Up late one night with this question, searching online for answers, I found the National Home Funeral Alliance, an organization that gives practical advice on everything from your particular state’s requirements about funerals (an illuminating read in itself) to body cooling and myths about dead bodies.

According to the NHFA, a home funeral can mean, among other things, that the family or community fills out the necessary paperwork, cares for and transports the body, makes coffins or shrouds or urns, and has a wake at home. A home funeral gives the family more control over the process, offering a more “healing experience for loved ones.” And home funerals are often less expensive and more environmentally friendly than “industry-led funerals.”

I would love to be able to tell my husband that I can give him a home funeral if he dies before I do. The problem is that when death comes, grief is so powerful that we need the people in our communities to help us walk through the rituals of death. And I’m not sure our communities are prepared to walk with us through home funerals.

But what if more of us decided to have them? How would it affect our culture’s approach to death? Would we, as Thurman suggests, be able to grieve in healthier ways? Would we feel more connected to our losses, more able to live fully in their wake?

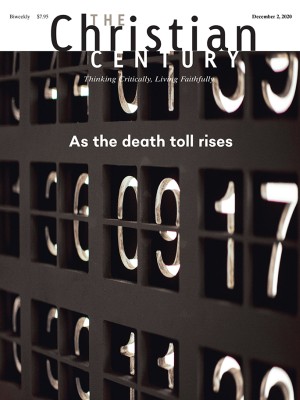

COVID-19 has wrought great horrors. It has also left communities unable to continue to ignore the specter of death and the ways it disrupts our lives. Families have been unable to say good-bye to their loved ones in person. Many have had to forego funeral homes and public mourning all together. When I hear these stories of unresolved grief and imagine myself in the same situation, I wonder if it’s time to reconsider the old traditions and bring death home again.

Portions of this article were adapted with permission from Awakened by Death: Life-Giving Lessons from the Mystics (Broadleaf Books). A version of this article also appears in the print edition under the title “From home to funeral home.”