The church under Putin: Nationalism and Russian Orthodoxy

Since the passing of the Soviet era, the Russian Orthodox Church has aligned itself closely with the Russian government and especially the nationalist strategies of Vladimir Putin. In the speeches of Orthodox Patriarch Kirill of Moscow, “Orthodox civilization” is interchangeable with “Russian civilization.”

Following a long Russian Orthodox tradition, Kirill likes to contrast Russia with secular Western nations. In Belgrade in November 2014, the patriarch argued that Western nations had “abandoned their Christian identity.” He identified both liberal democracy and secularism as enemies of Orthodoxy and envisioned a “clash of civilization” in which Russian Orthodox values stood against those of the secular West.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Kirill’s vision of Russian civilization transcends Russia’s current boundaries, encompassing all Orthodox people “living in the countries of historical Rus’—namely Belorussia, Russia, and Ukraine.” The Orthodox Church had risen to the defense of Russia in the prerevolutionary past, he maintained, and it must do so again to defend the nation’s values and unity.

Russian sociologist Aleksandr Verkhovsky has argued that the patriarch’s nationalist ideology, like Putin’s, is a logical and perhaps unavoidable response to the disintegration of the Soviet Union. The patriarch’s vision is not the only nor the most extreme form of Russian nationalism. Some ultranationalist groups have promoted the rehabilitation of Joseph Stalin and Stalinist policies so as to “cleanse the country of its internal enemies.” Verkhovsky argues that Kirill’s position actually has a “moderating influence.”

In fact, Putin’s efforts to annex the eastern part of Ukraine backed the patriarch into a corner. Kirill’s talk of Orthodox civilization provided an intellectual justification for Russia to annex Ukraine, but the violence wrought by Russian forces in Crimea and eastern Ukraine conflicted with the church’s historic mission as mediator and peacemaker. The patriarch cannot, without considerable cost, criticize Putin’s actions in Ukraine, but at the same time he tries to stress the need for peace, negotiations, and an end to civil strife—an implicit response to the government’s military assault.

While trapped by his political alignment with Putin, the patriarch has emphasized theological education in a way that has benefited the church and provided the context for at least some transformation. He has begun restoring theological institutes and seminaries and raising the level of theological education for clergy and laypeople. This effort offers some help to movements that challenge the status quo, particularly in the provinces.

Two of the most striking developments are in the provinces of Ivanovo and Vladimir, both to the north of Moscow. Sergei Filatov, one of Russia’s leading scholars of religious life, observes that in Ivanovo, the bishop who served from 1977 to 2006 and his successor have given “a large amount of freedom and independence” to their priests, and this has led to relatively free spiritual and intellectual developments. The archbishop created a center for the study of church history and current problems and appointed both clergy and secular scholars to the advisory board. The center convenes yearly conferences involving clergy, scholars, and members of the local government.

In Vladimir, leaders have focused on restoring and strengthening both men’s and women’s monasteries, and the number of monasteries has increased dramatically. The Vladimir diocese is also distinguished for its educational programs and social outreach.

“While their leaders remain conservative in their theological beliefs,” Filatov noted, “they are not wedded to the past in their activities. They are developing a different form of Orthodox conservatism, which is very socially oriented and emphasizes social outreach and compassion for the marginalized.” It may be that Kirill’s emphasis on renewing theological education will spark a much more diverse and vital religious life.

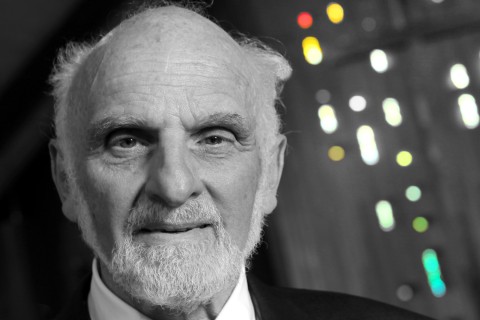

Signs of alternative movements within the Russian Orthodox Church surfaced also in relation to the legacy of Father Alexander Men (1935–1990), an Orthodox priest who was murdered in 1990. Men’s writings struck a deep chord with many people. His life’s work, Son of Humanity, has sold more than 6 million copies, and his multivolume History of Religion: In Search of the Way, the Truth, and the Life has been published in tens of thousands of copies. During his lifetime, the several small parishes outside Moscow in which he served were havens for young members of the intelligentsia.

But for many years, church bookstores in Russia did not carry his books. He was often considered an outlier, a non-Orthodox priest, whose ecumenical ideas were viewed with contempt. Recently, however, the official church position on Men has begun to change.

In 2014, Kirill paid homage to Men’s lasting achievements as a parish priest and a missionary teacher during the dark years of the Soviet era.

In September 2015, the publishing house of the Moscow patriarchate for the first time published Men’s writings in a 15-volume Collected Works. The first volume, Son of Humanity, was presented by the church in September during a commemoration of Men’s life.

Part of what made Men so threatening to the political and church establishment was his belief that “knowledge of God [is] a process; it is neither complete nor fixed in time.” This view made Men a natural reformer, and hence a source of tension in the church.

That tension was evident in the choice of topics at the commemoration events. Archpriest Alexander Borisov of the Church of Saints Kosmas and Damian in central Moscow, who had known Men since childhood, spoke eloquently about Men’s spiritual legacy, especially in relation to the Soviet past: “Son of Humanity is the most anti-Soviet book ever published in Russia.” By his writings and example, said Borisov, Men taught Russians how to live in relation to Christ and in relation to an oppressive state.

Borisov drew from Men’s book Why Is It Difficult for Us to Believe in God? to underscore several key points of Men’s work: “Christianity is not the perfect truth. Christianity is still evolving, still becoming more perfect, and is still in process.” Men also wrote, “I don’t believe in God, I believe to God,” a statement which, according to Borisov, “expresses a different attitude than we are accustomed to hearing. Christianity is not a warm oven in which we can relax. We have to cultivate our faith in order for it to grow and develop, and this process may make us uncomfortable.”

Borisov made no mention, however, of one crucial element of Men’s theology: Men emphasized that in order for the Russian Orthodox Church to speak effectively, it had to come to terms with its past. The church has to seek repentance for its association with violence and its complicity in acts that betrayed Christianity, both in the czarist and Soviet eras. Repentance, Men pointed out, is the first step to healing, and he noted that the Greek term “to repent” means “to rethink one’s life.” The church took no such step during Men’s lifetime, nor has it done so since.

At the very end of the commemoration, a recording of an interview that Men gave the summer before his death was played. It was mesmerizing for the audience to hear his voice again, especially as he spoke about the dangers of charismatic political figures. “Christ openly told his disciples that Caesars have power over people, but it must not be like that among you. Do not let the Caesars create idols for you.” The implications of these statements for the contemporary situation were not acknowledged, but they were hard to miss.

The Russian Orthodox Church is not nearly as placid and compliant on the inside as it appears on the outside. As educational standards for priests rise, external and internal tensions are likely to grow. That could lead to a healthy dialogue in the church about a long-standing demon—the political use of religion.